Torre Farfán’s Fiestas de Sevilla:

A Journey with Stirling Maxwell

Hilary Macartney

University of Glasgow

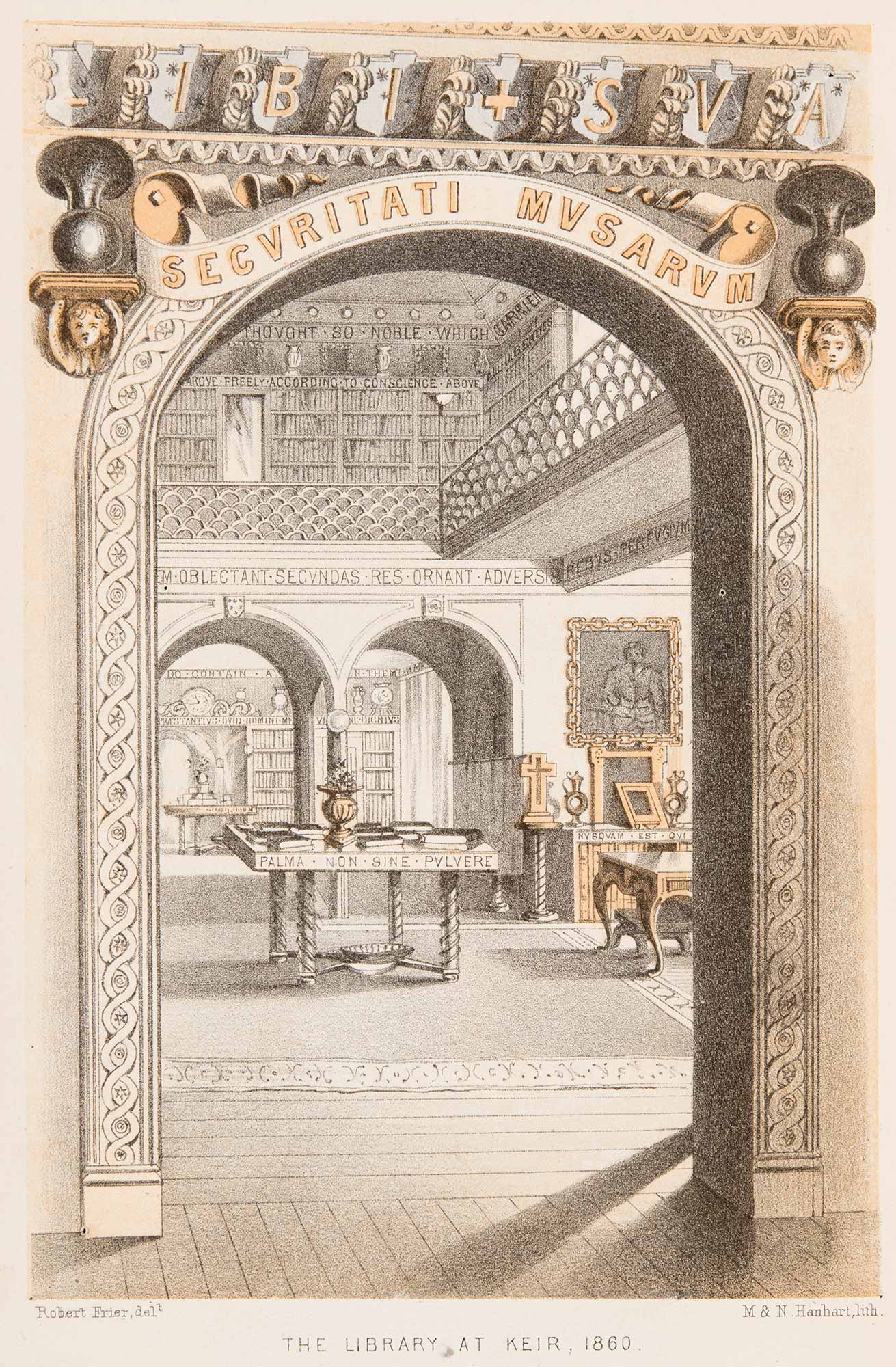

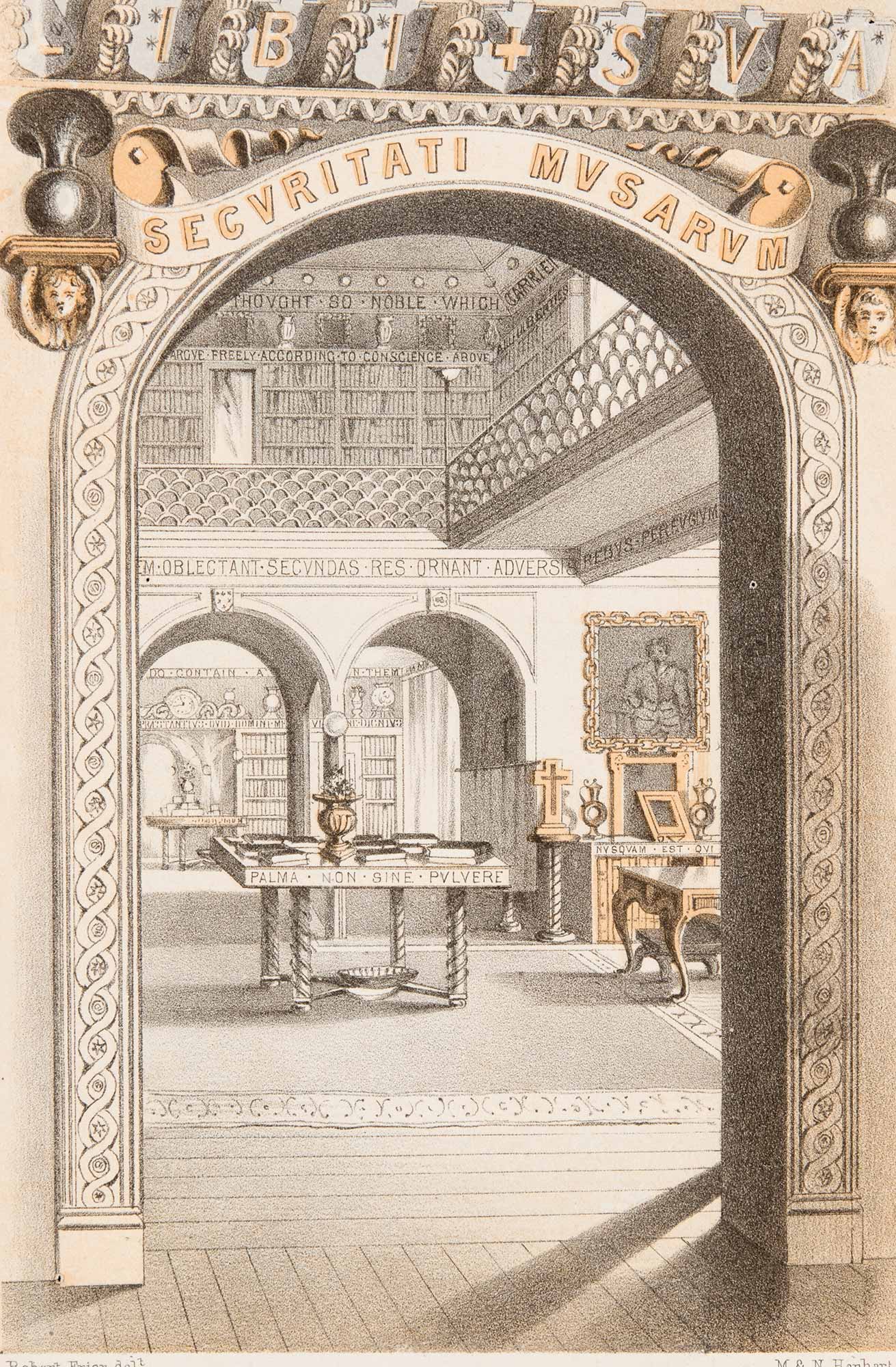

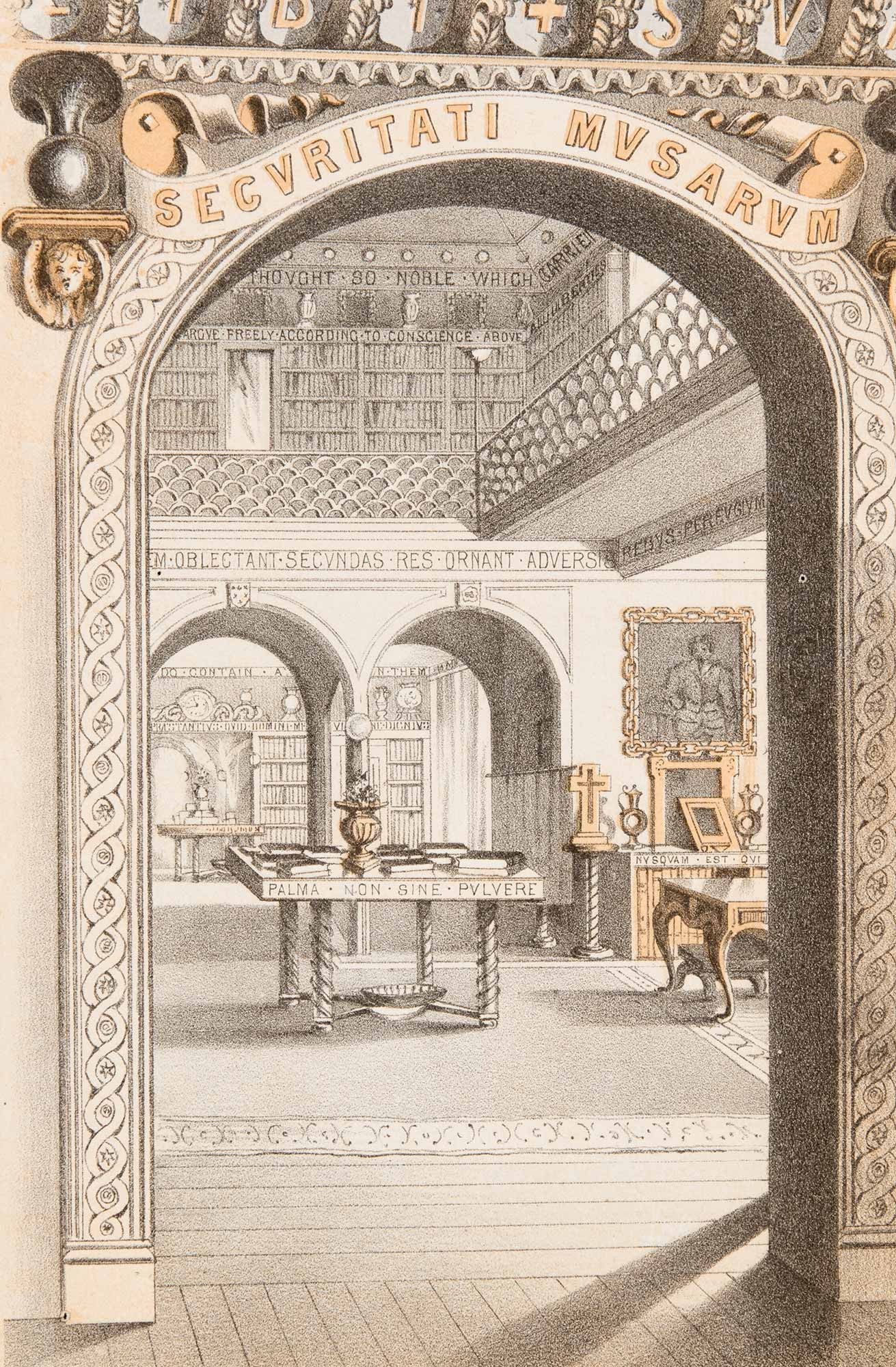

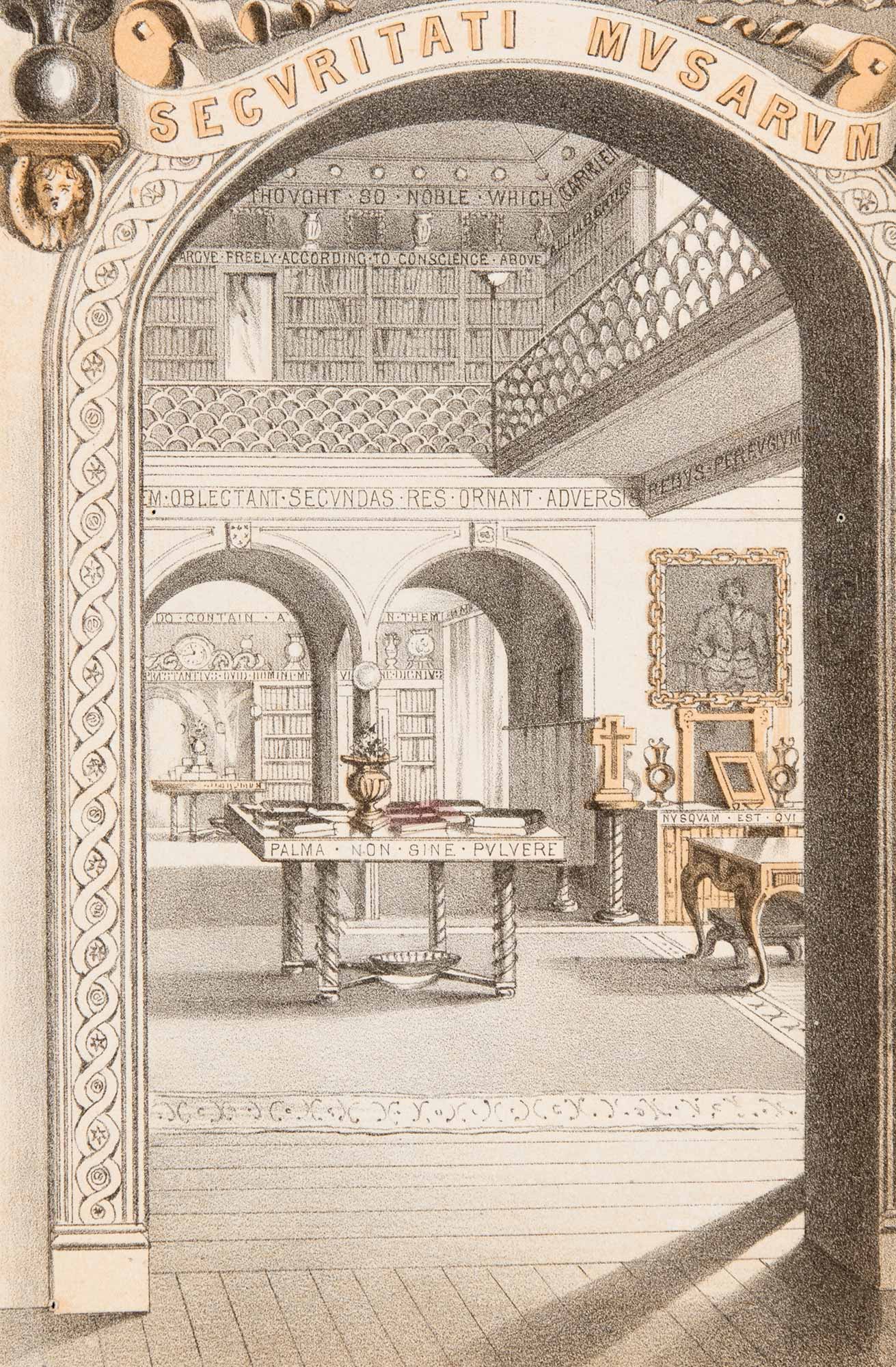

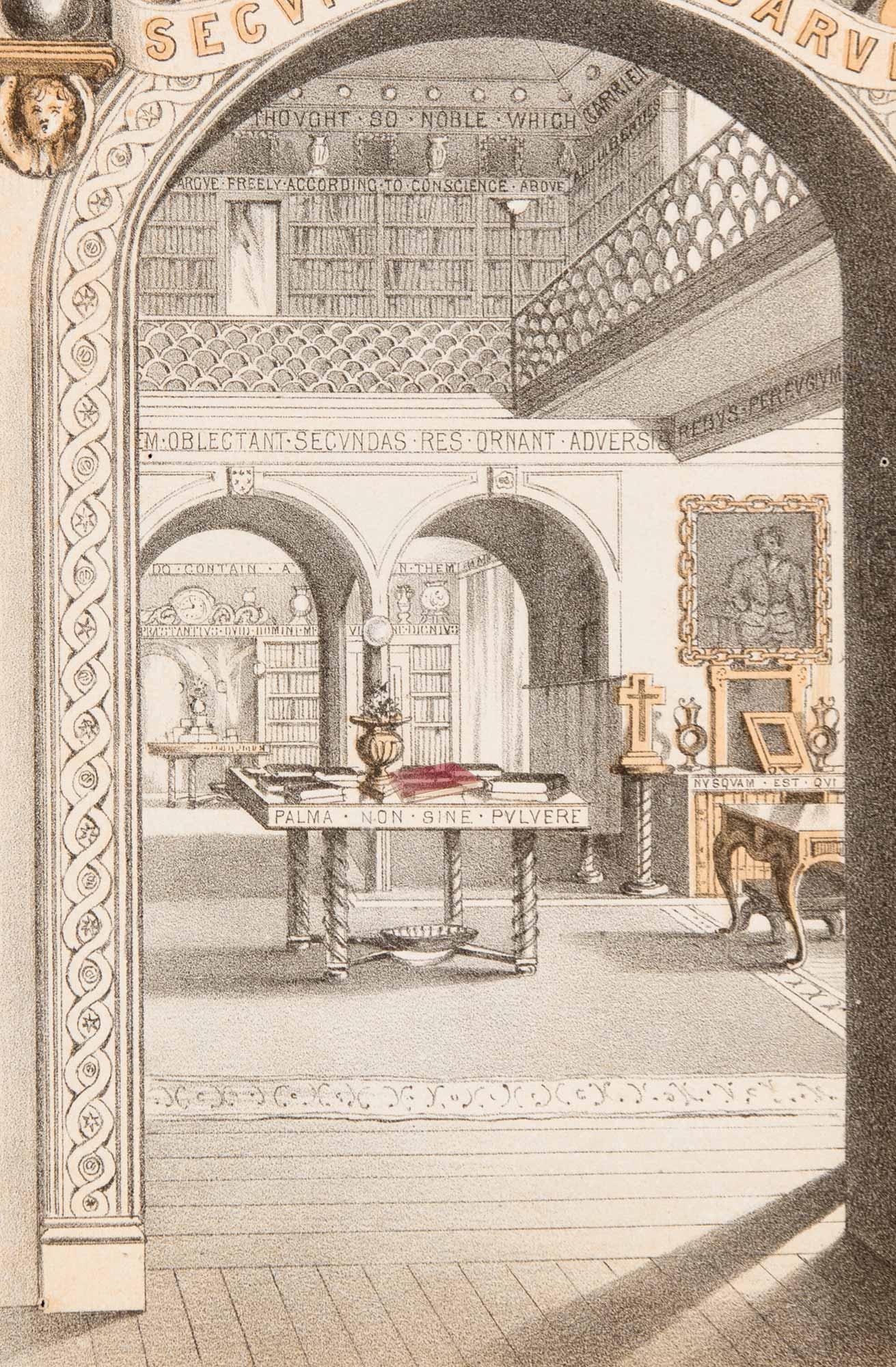

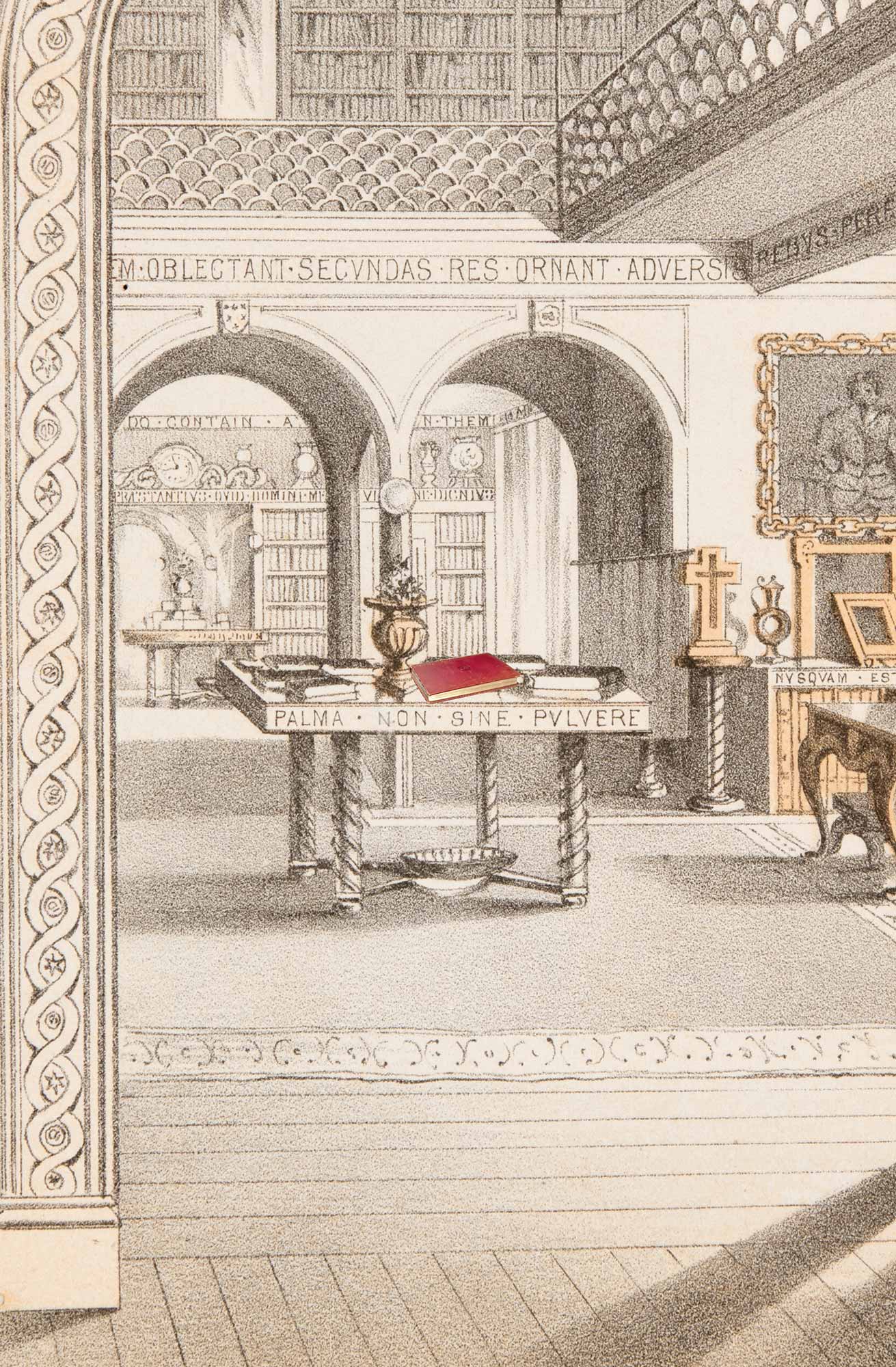

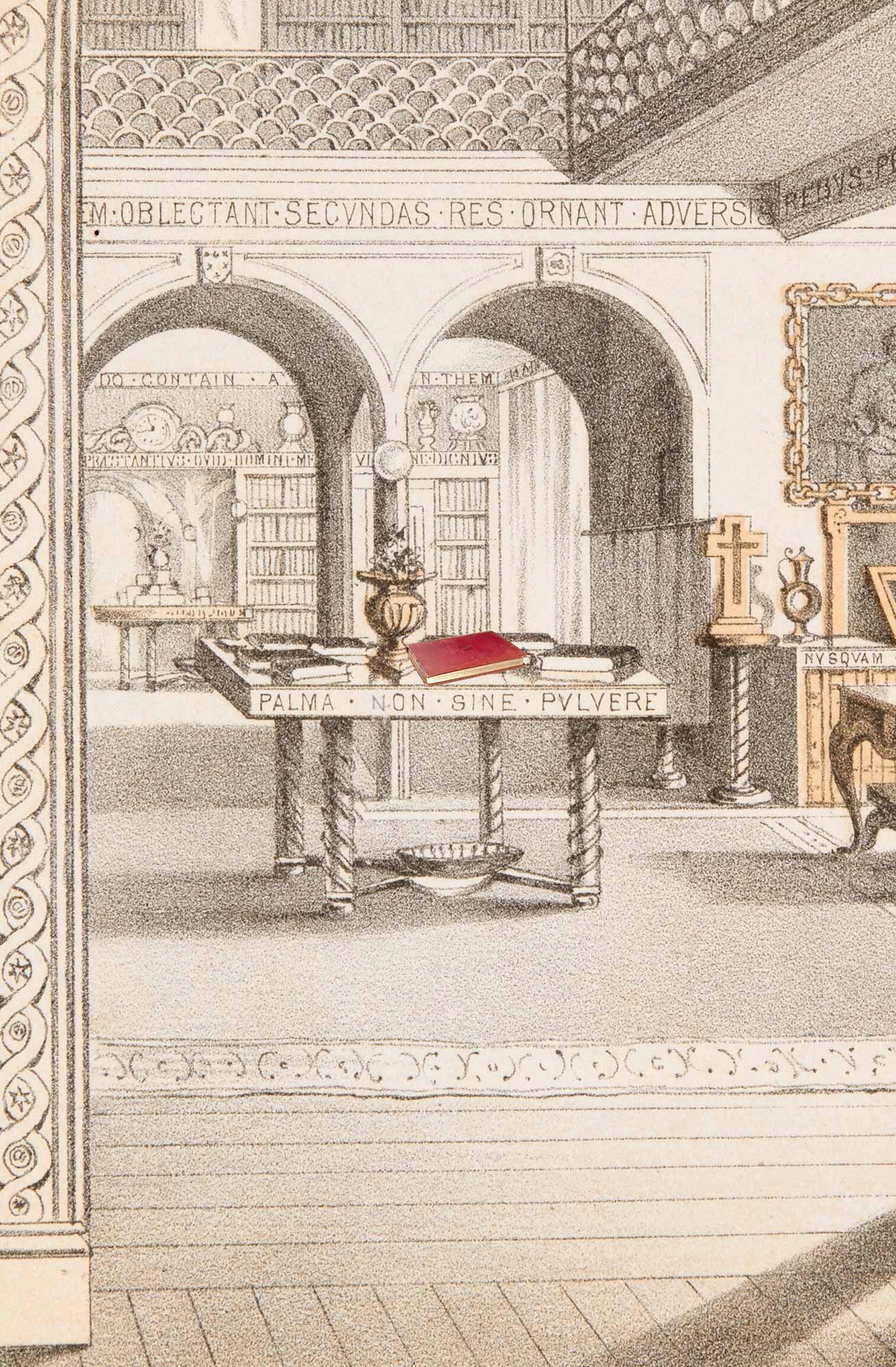

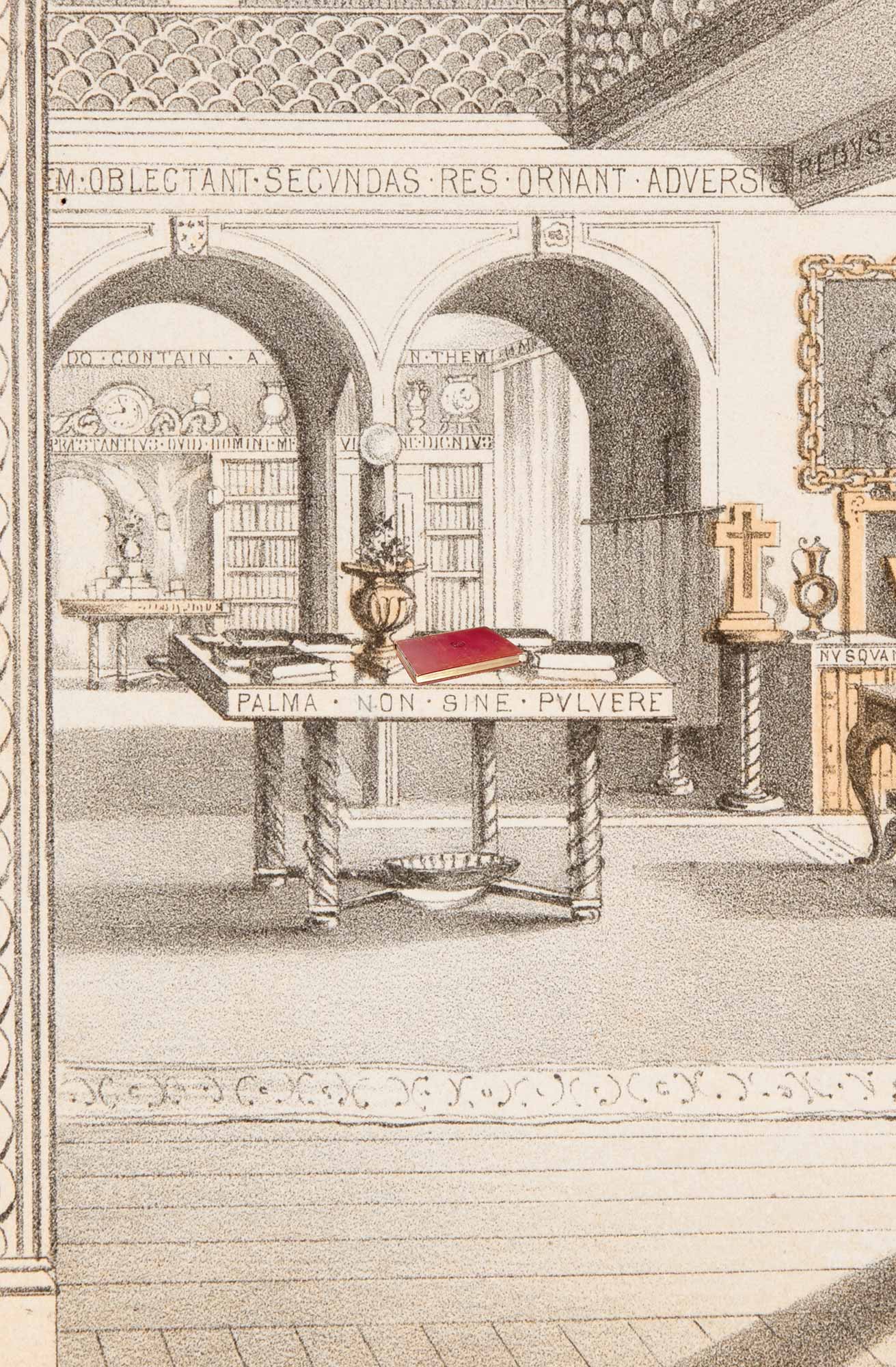

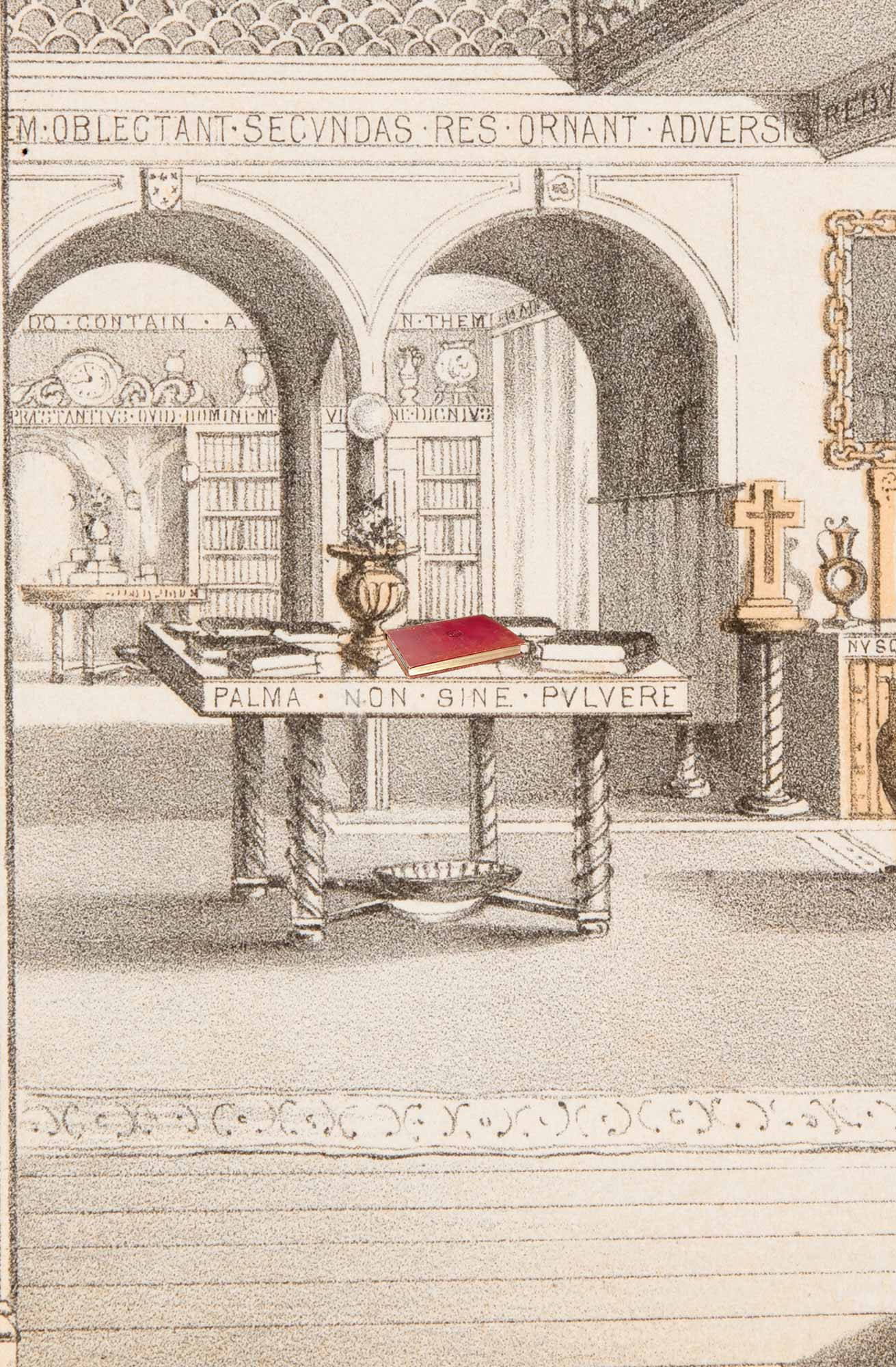

Keir Library

In the 19th century, a Scottish scholar and collector, William Stirling Maxwell, formed an important library, which included a collection of around 300-400 Early Modern festival books. Find out more about Stirling Maxwell and his collection.

Though frequently written from a partisan viewpoint, with exaggerated descriptions and idealised illustrations, festival books nevertheless provide valuable records of historical celebrations and the ephemeral art and architecture created for them. It was often said that the illustrations and the text helped to explain what could only be fully appreciated by being at the original event itself. 1

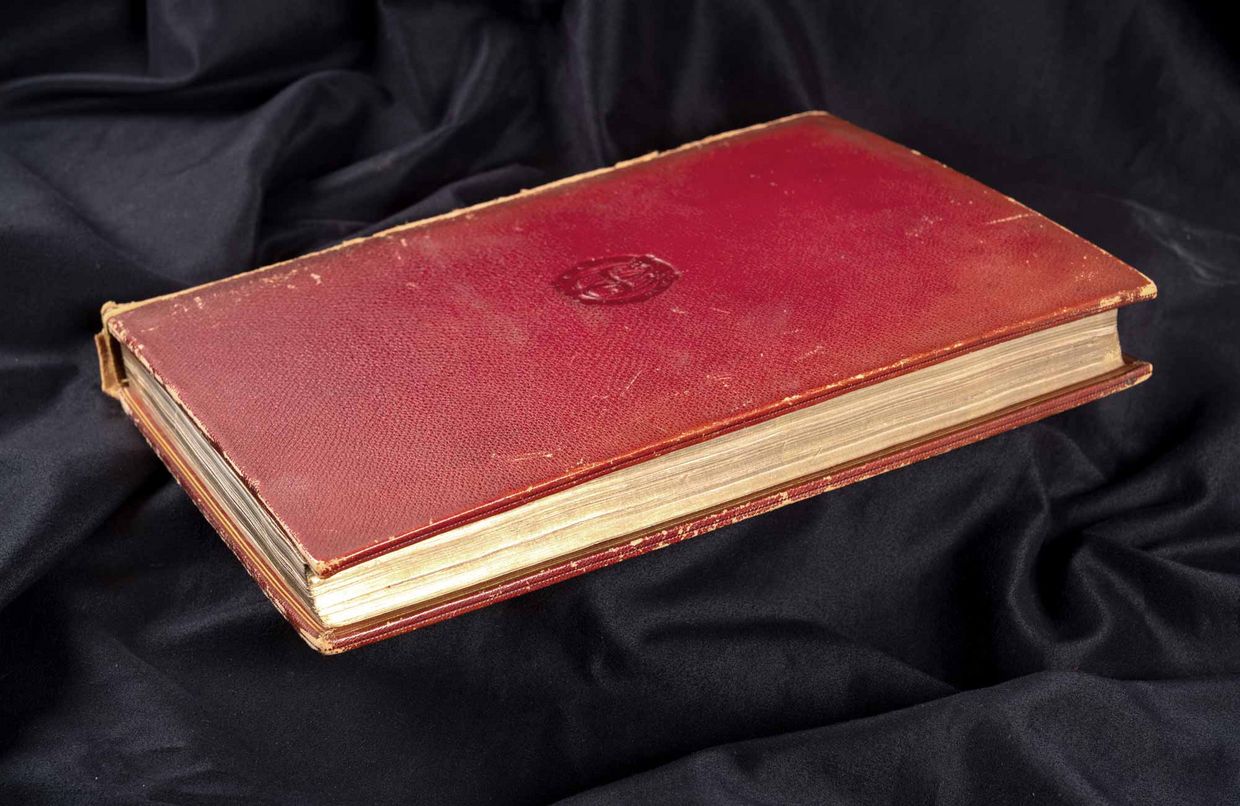

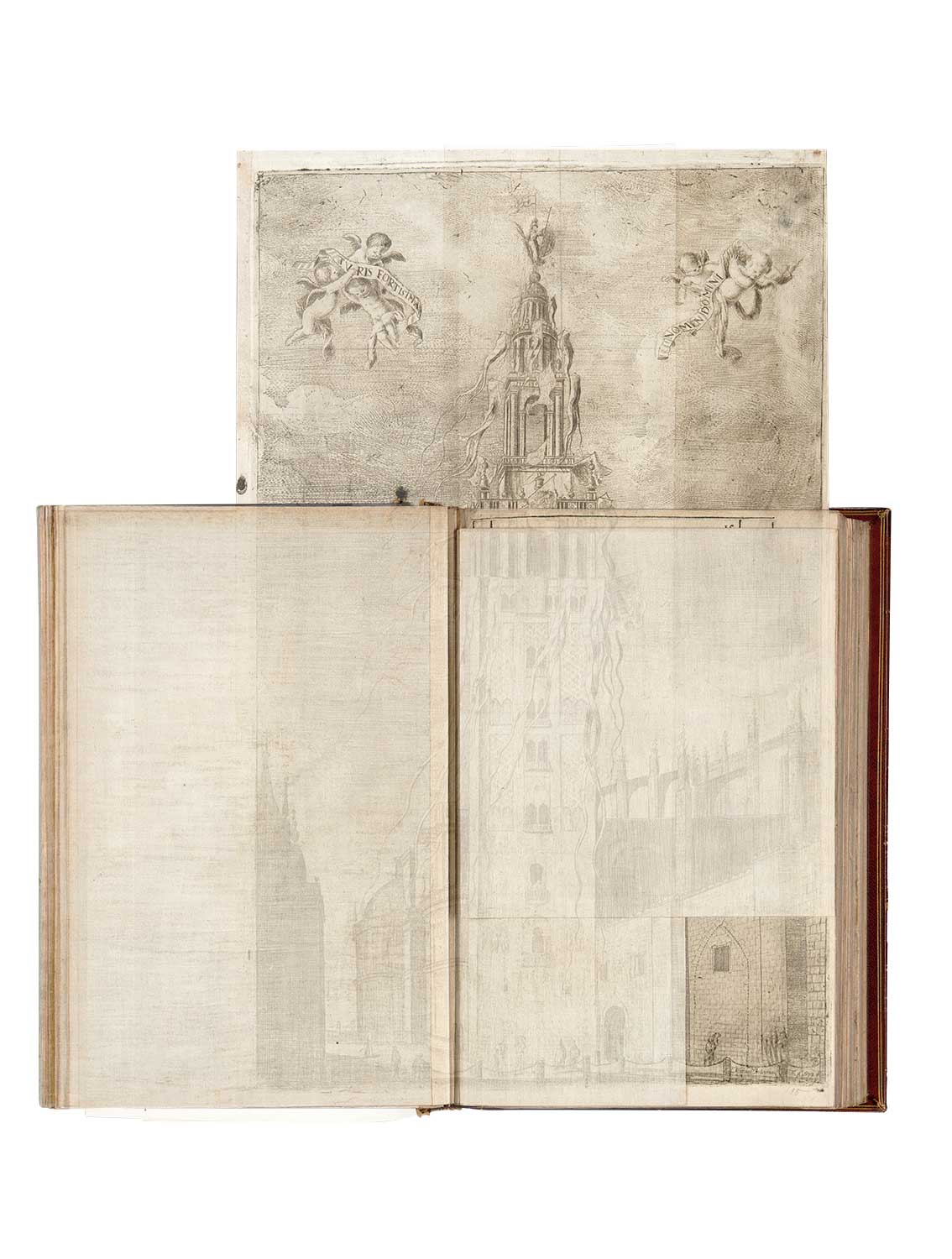

One of the most prized festival books in Stirling’s collection was the volume known as the Fiestas de la S. Iglesia metropolitana y patriarcal de Sevilla, about festivities held at Seville Cathedral in 1671.

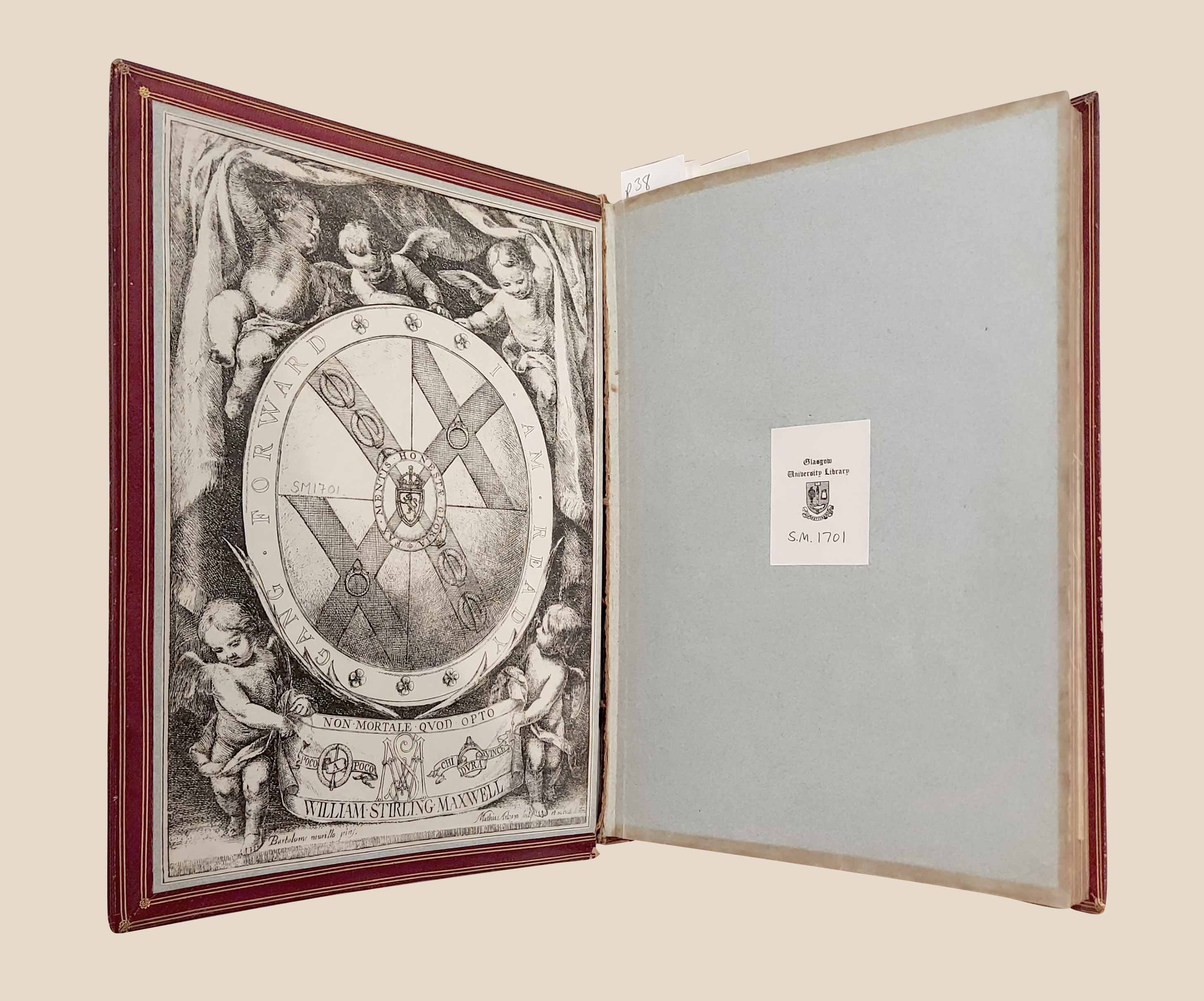

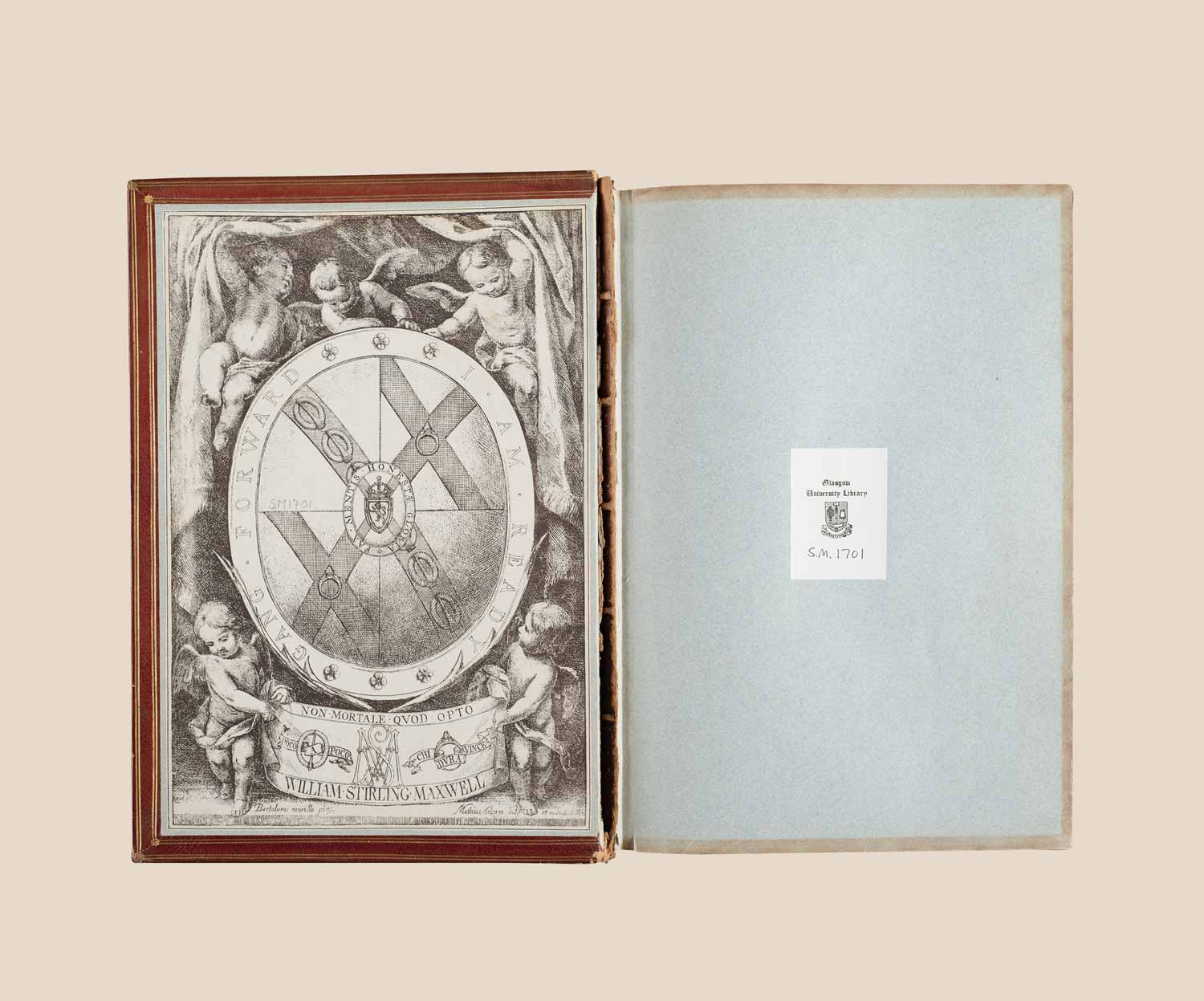

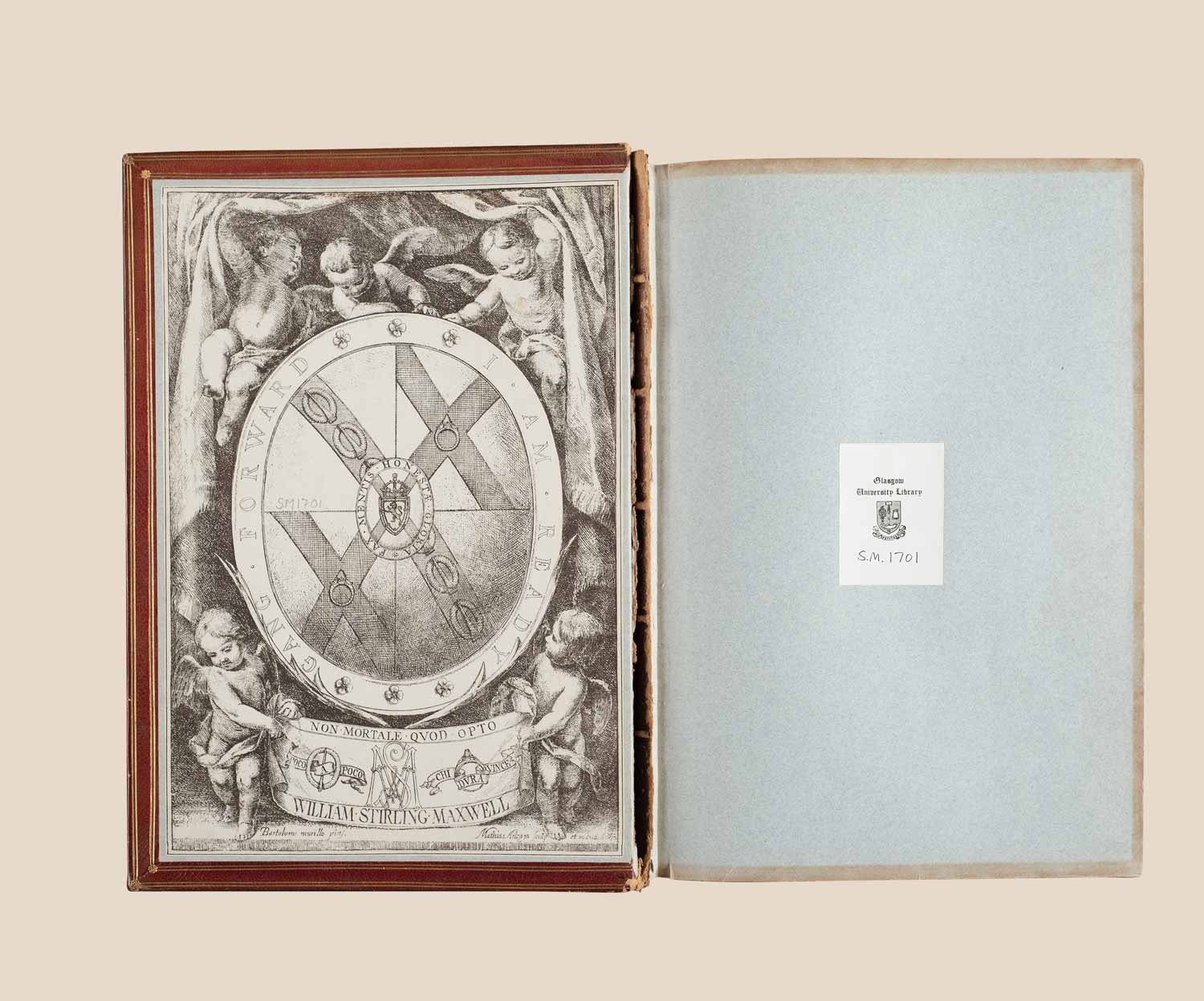

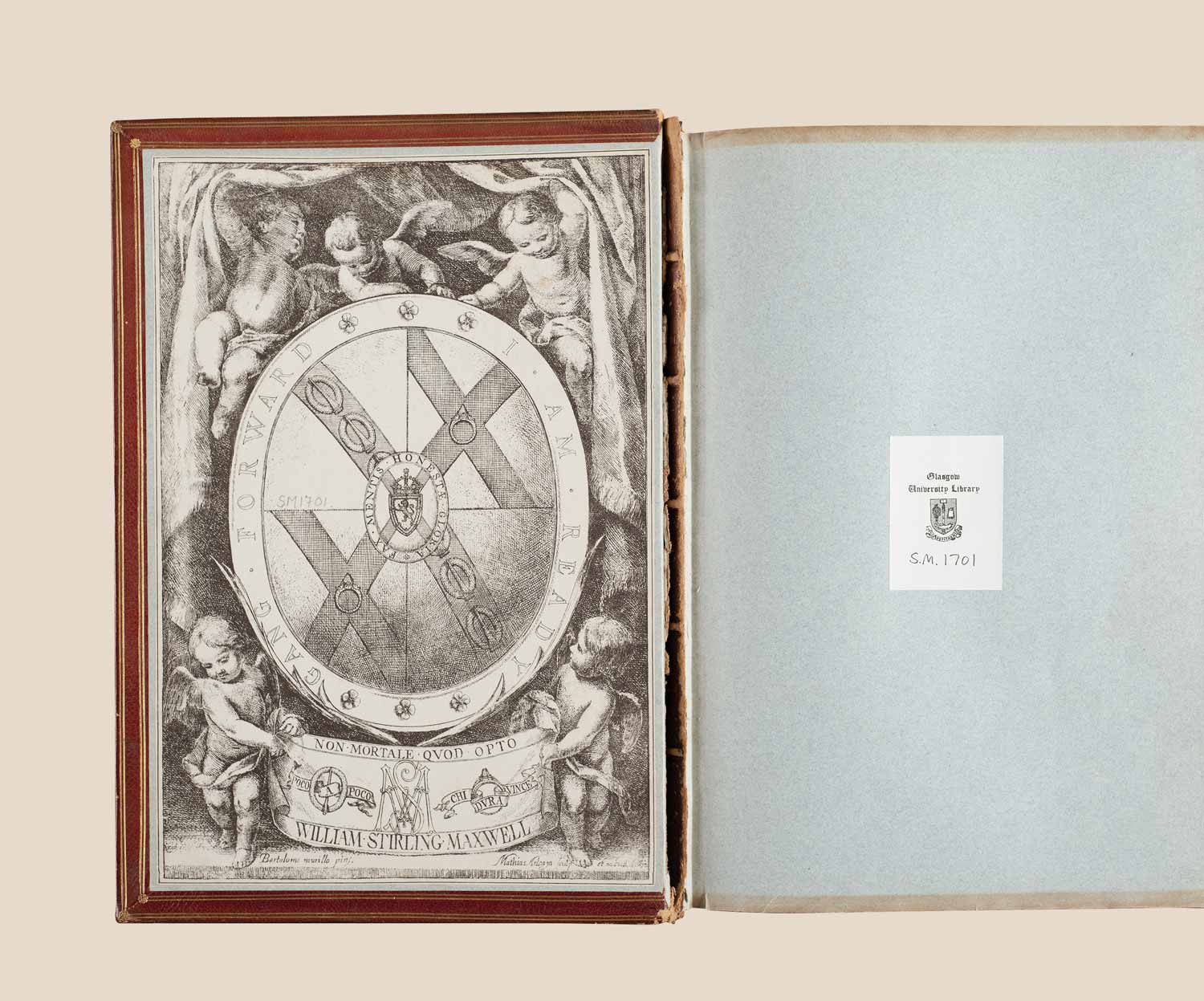

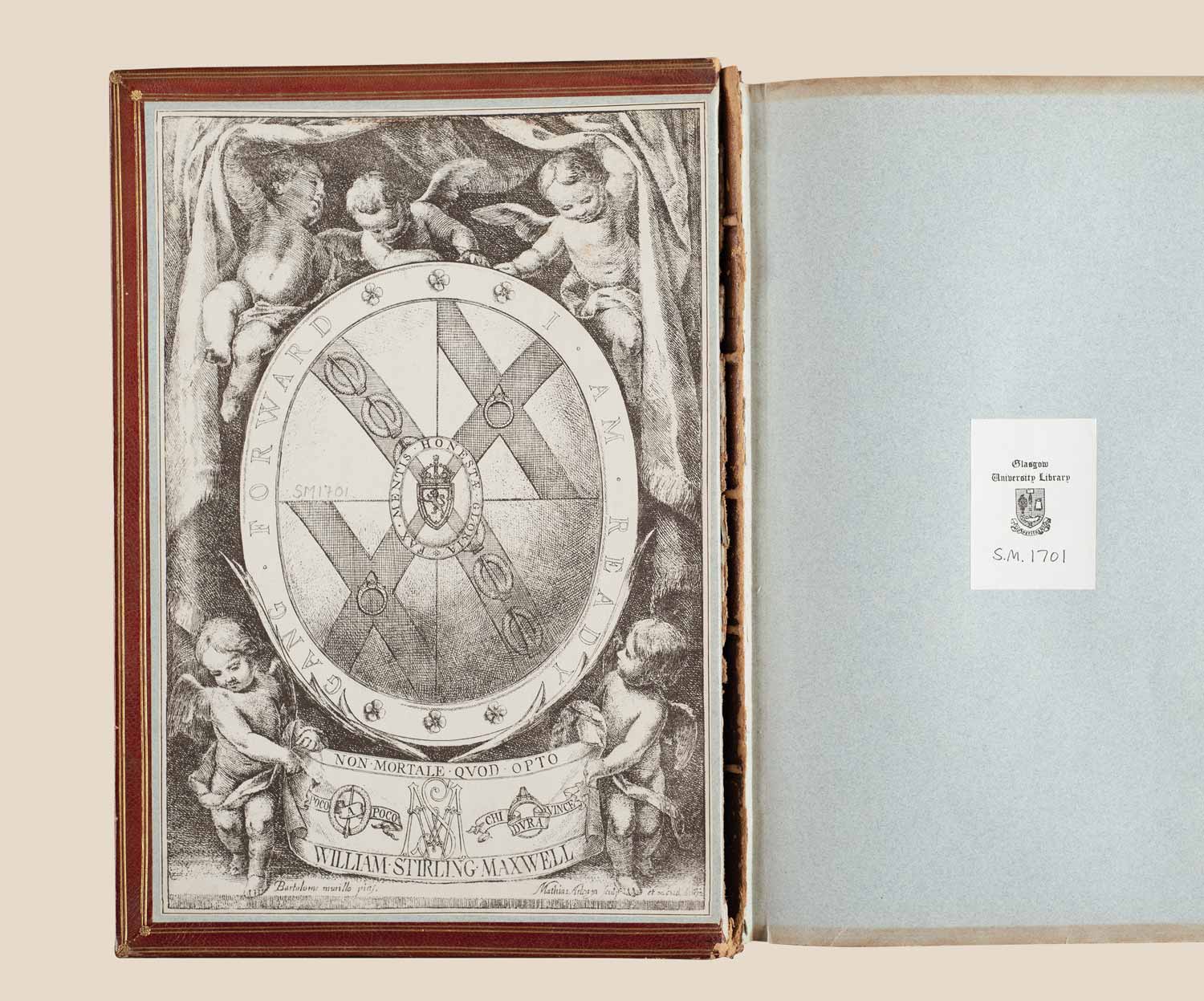

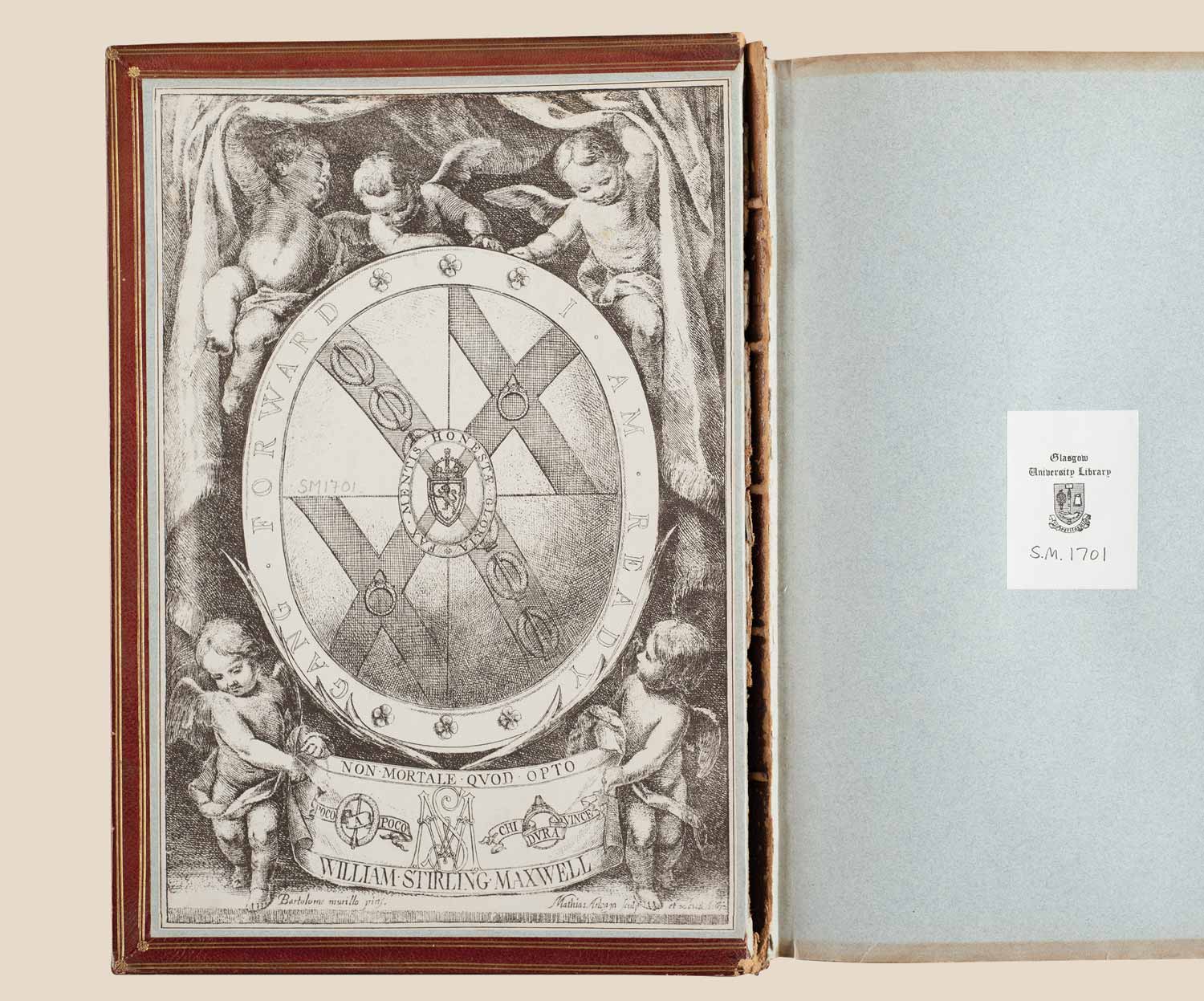

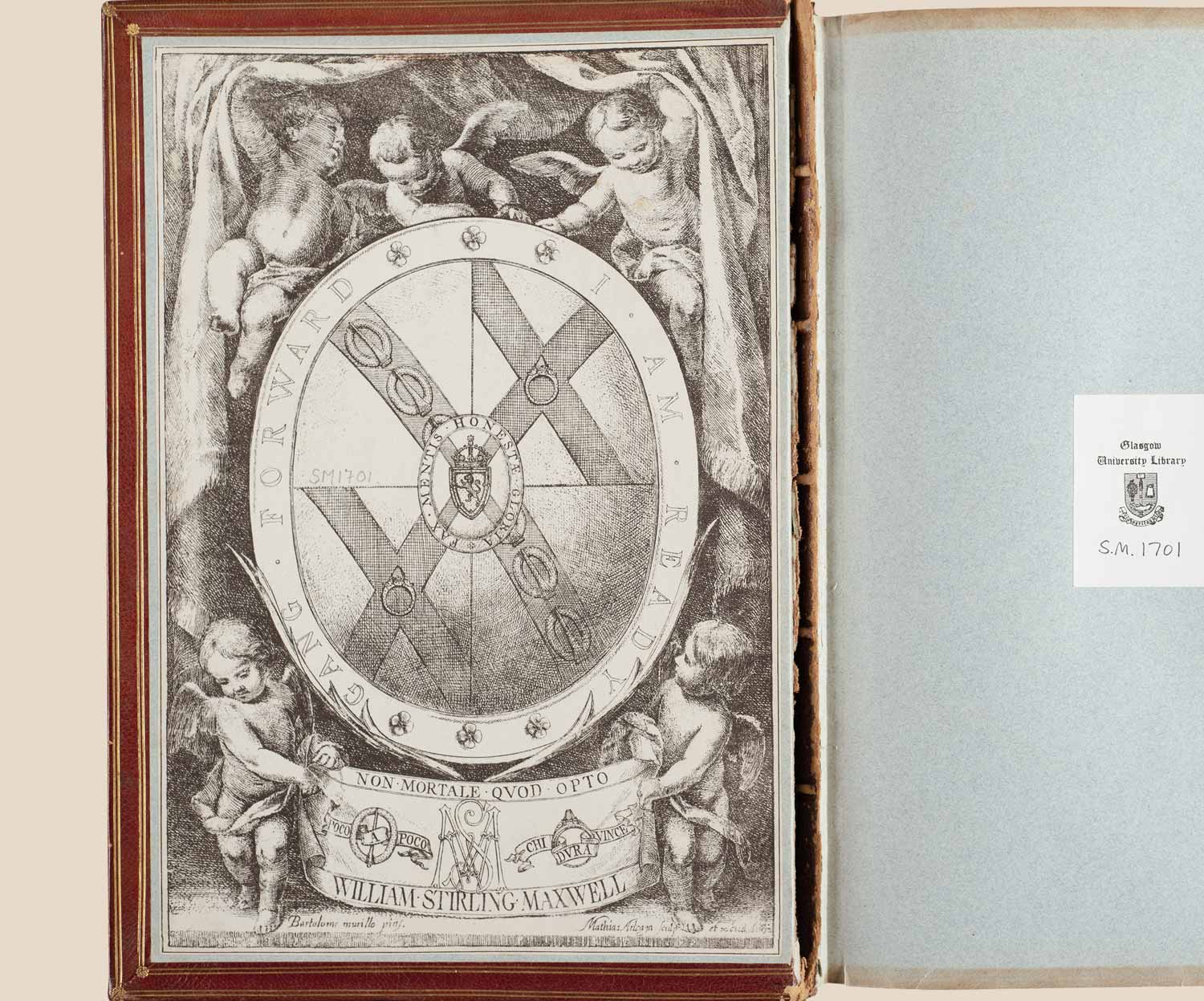

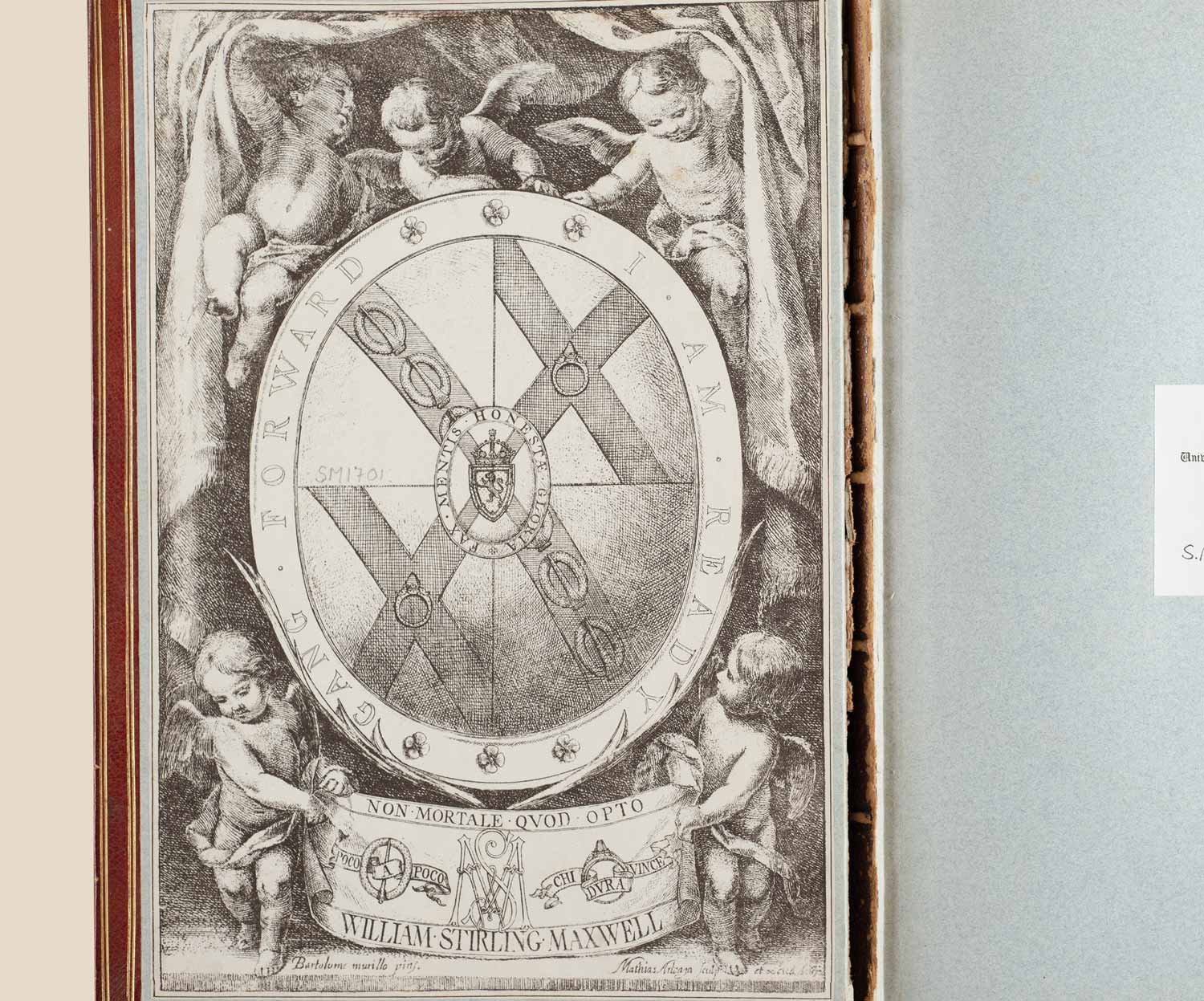

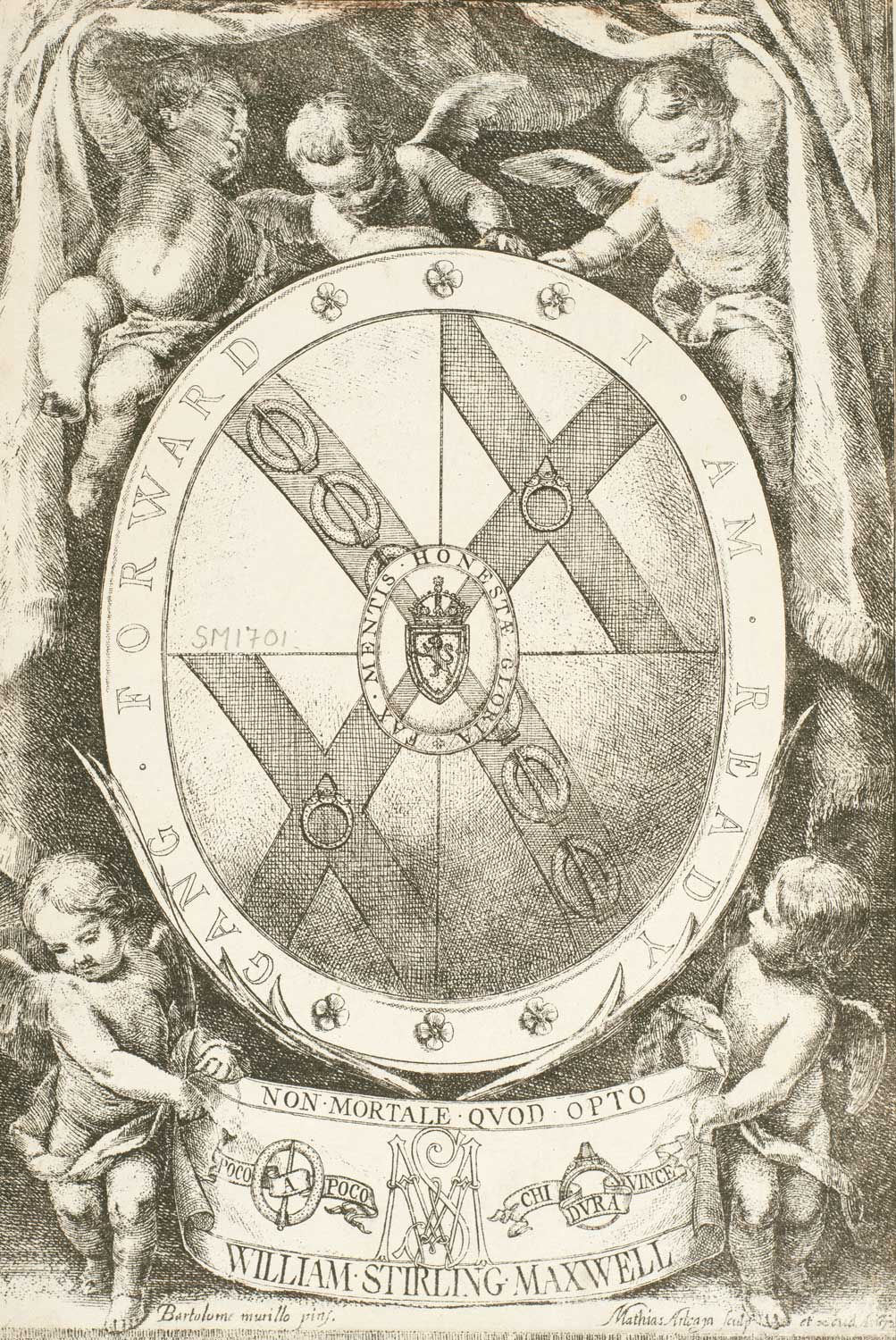

Appropriating the Book

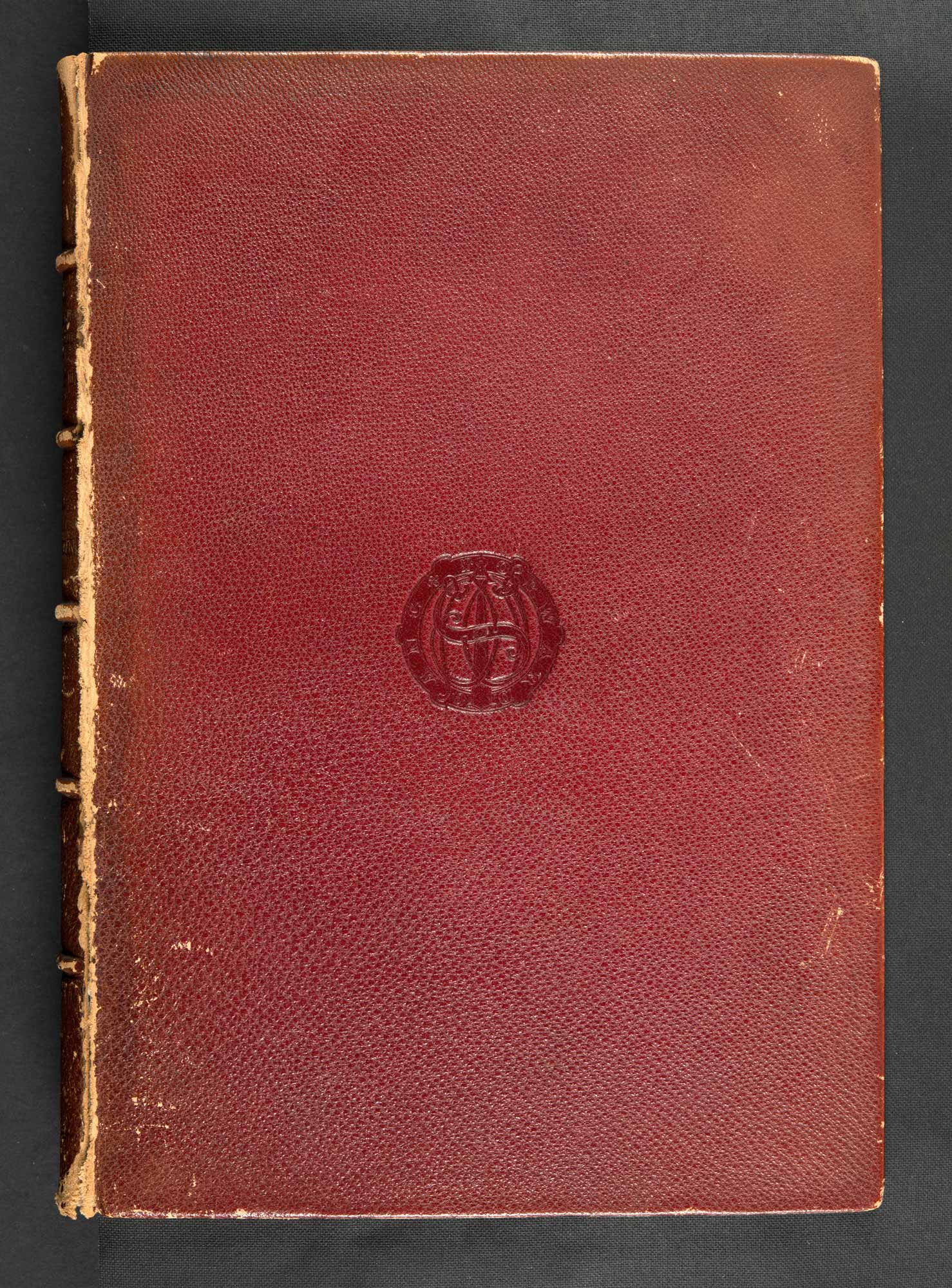

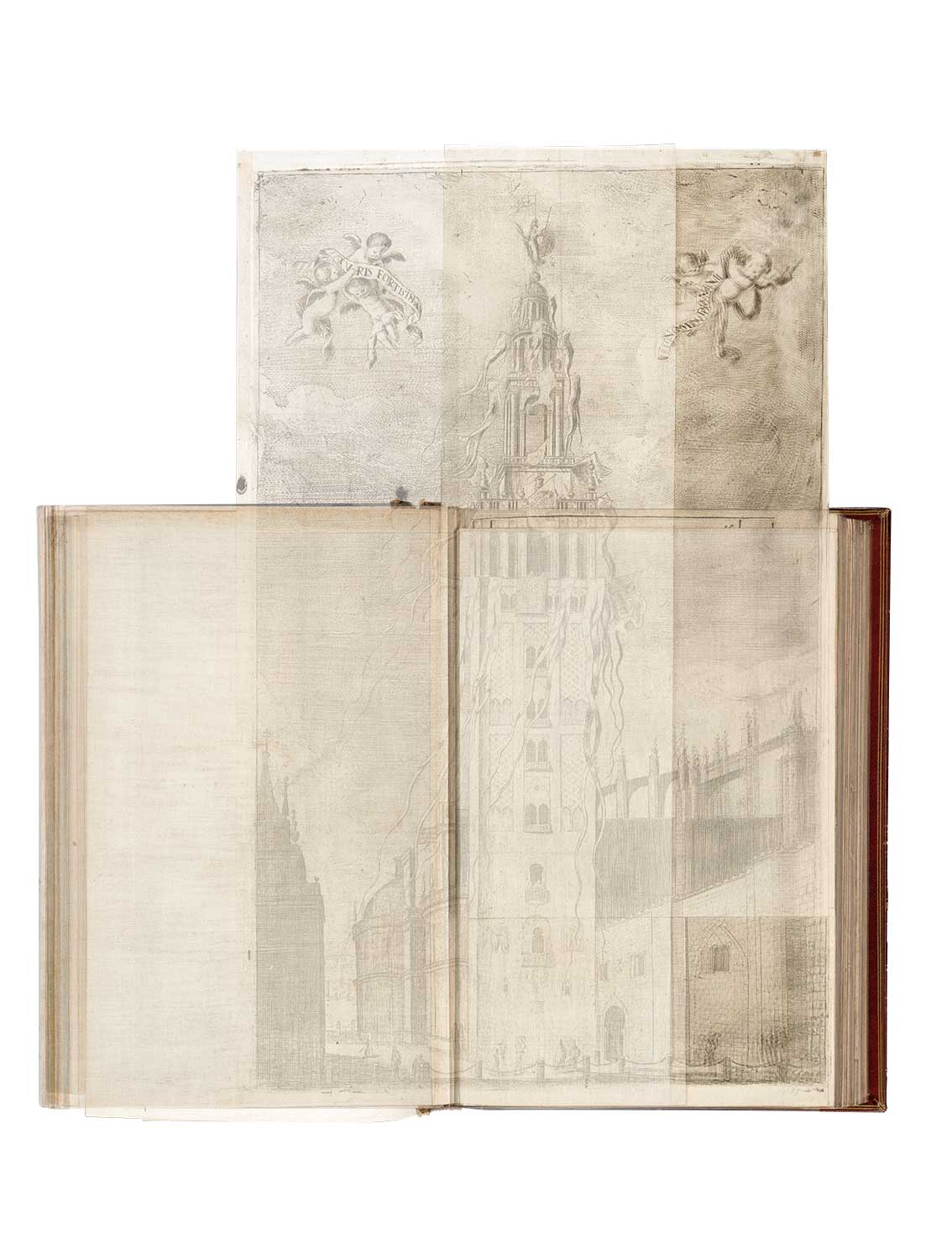

Like most 19th-century collectors, Stirling personalised his books by rebinding them. He would also insert his bookplate or ex-libris slip. This one on the left is adapted from one of the illustrations in the book itself.

Learn more about Stirling Maxwell’s copy of the book and about aspects of object conservation.

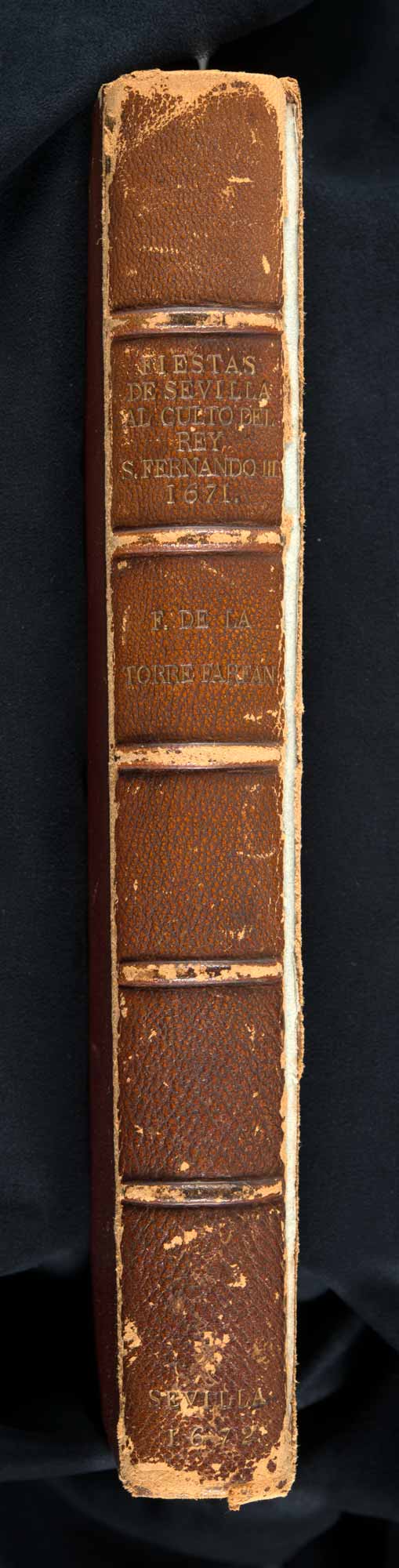

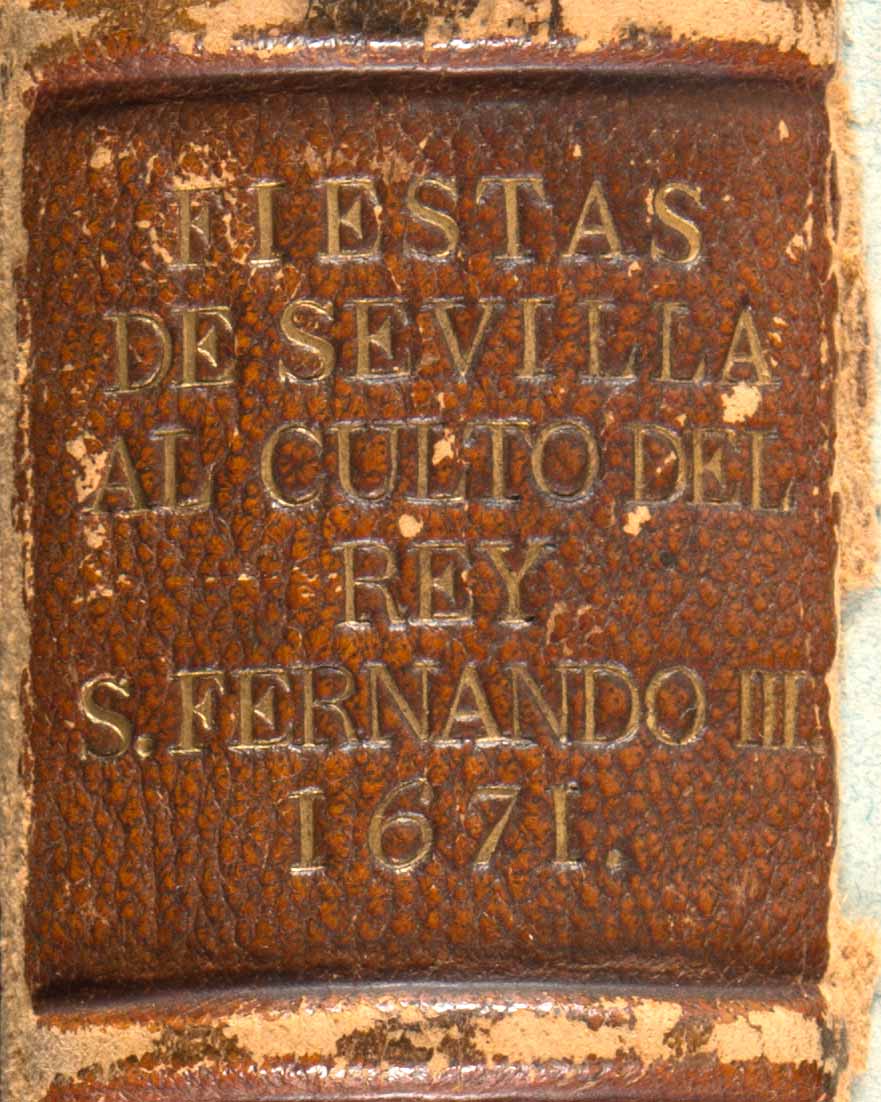

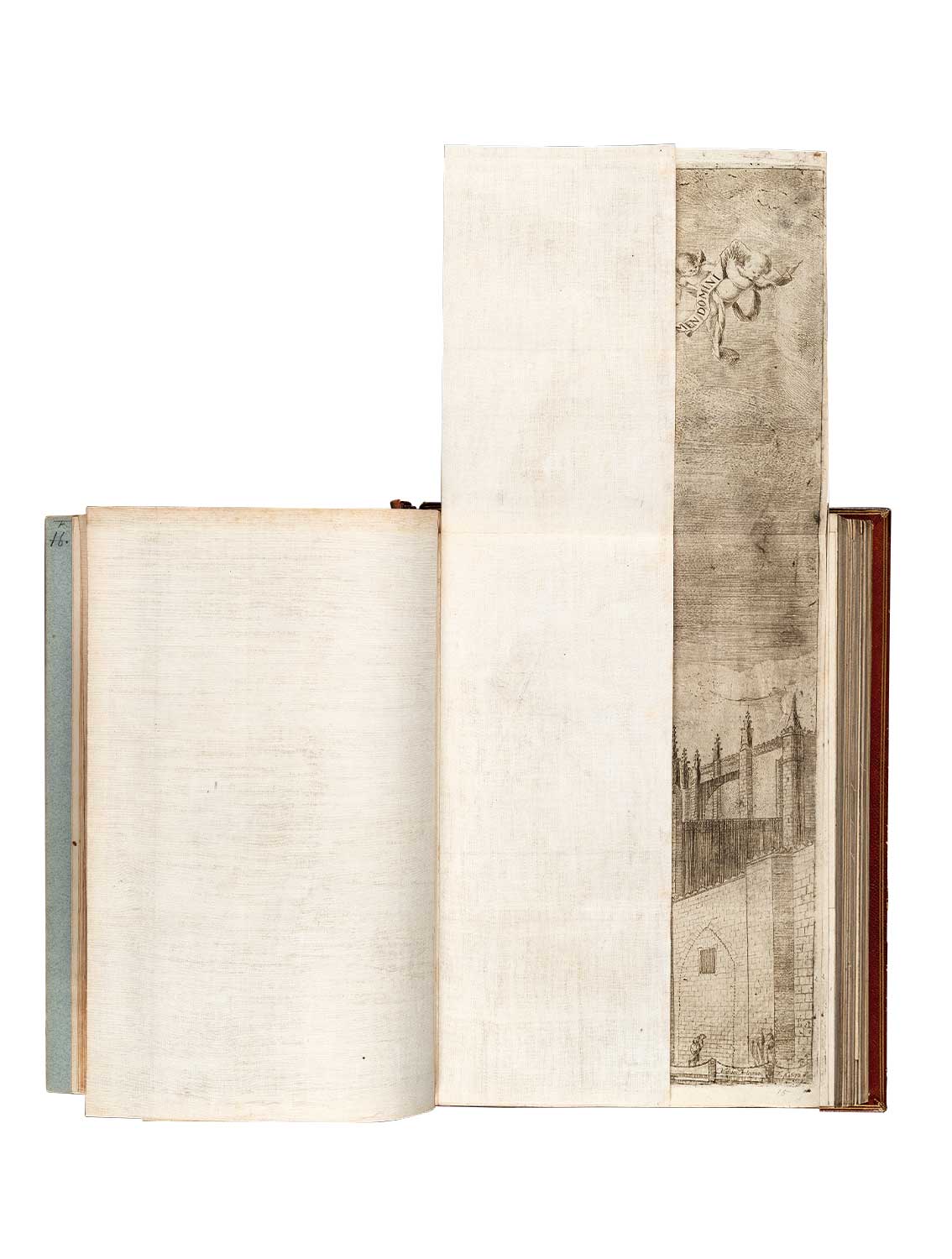

Original Binding Type

When Stirling acquired it, the book probably looked more like this – with a vellum binding which became discoloured over the years, and hand-lettered title on the spine. Nowadays, conservators prefer to consolidate the condition of books, preserving original materials.

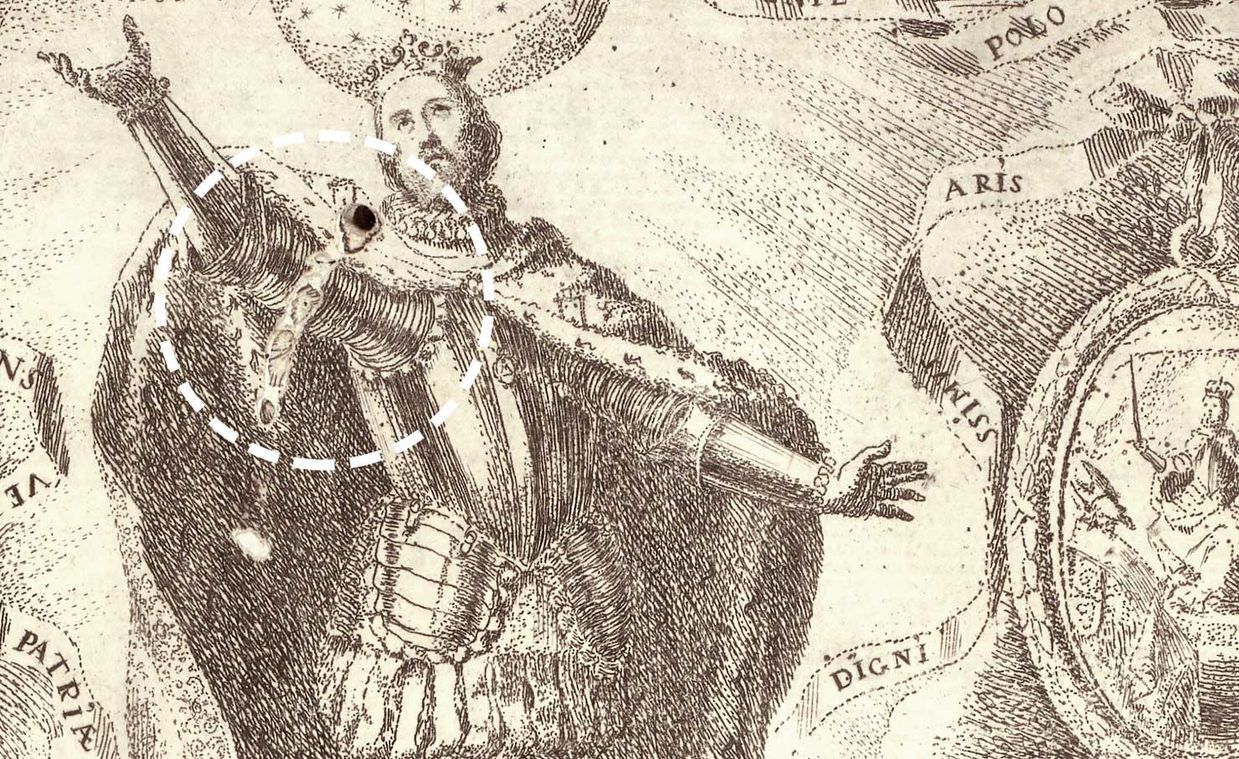

Typical page damage

Pages would often get torn or worms would eat some of the paper, leaving holes like this one on St Ferdinand’s shoulder.

Page patching

The pages in Stirling’s copy have been patched up – like the right edge of this one.

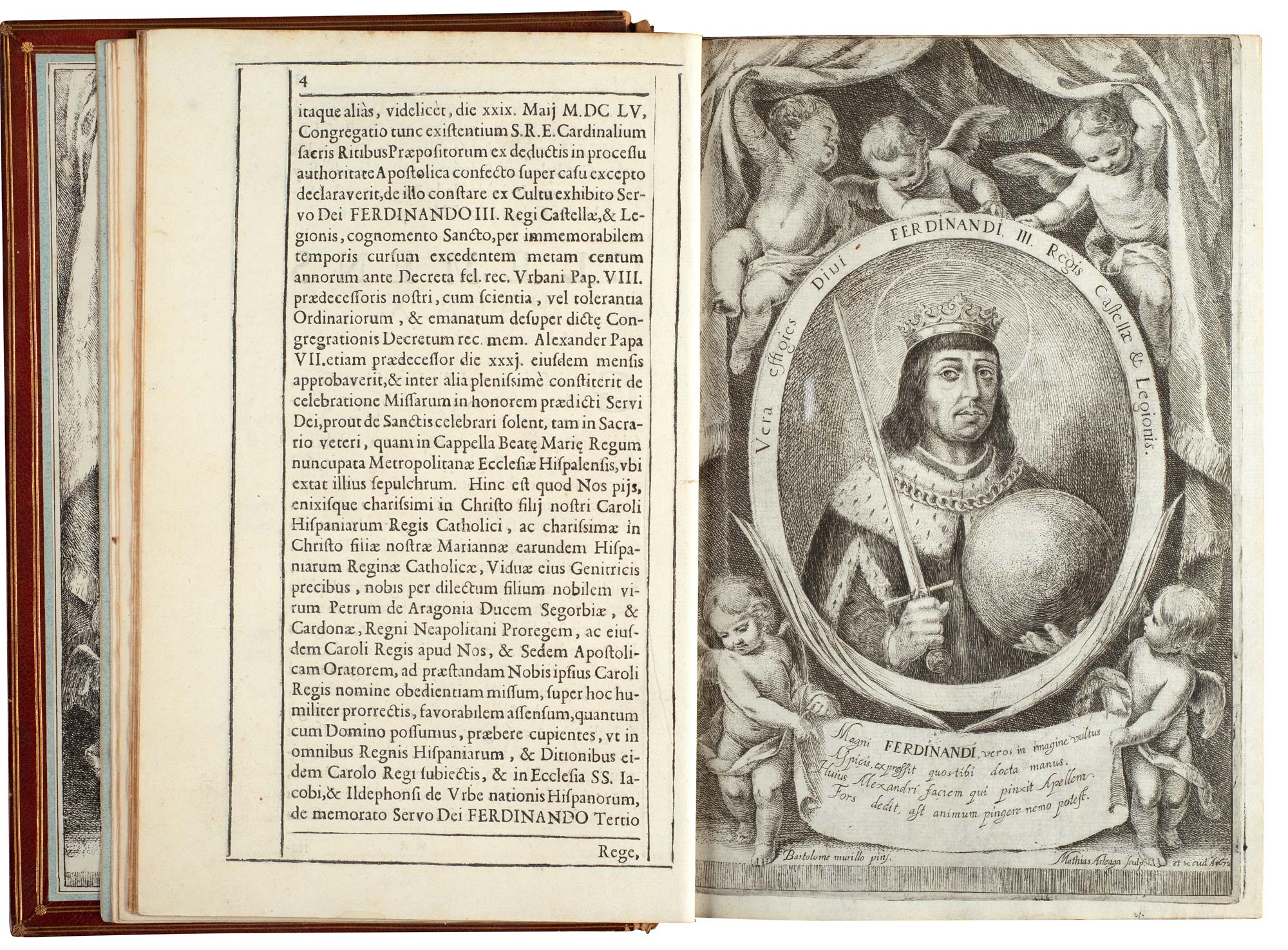

The Bookplate and the True Portrait

Stirling’s bookplate was adapted from an illustration of the “True portrait of St Ferdinand” in the volume itself. The “True portrait”, which was etched by Matías de Arteaga, is the only illustration in the book designed by Murillo. Stirling used the latest photomechanical printing technology to playfully refer to it by replacing the likeness of the saint with his own coat-of-arms, and the inscription below with his name, mottoes and heraldic devices. Click on the illustration to toggle between the bookplate and the “True Portrait of St Ferdinand”. 2

Stirling and the Fiestas de Sevilla

Stirling was aware of the artistic importance of the Fiestas de Sevilla as a record of the celebrations held in 1671 for the canonization of King Ferdinand III of Castile, who conquered Seville from Muslim rule in the 13th century.

Find out more about King Ferdinand III of Castile and Muslim Spain.

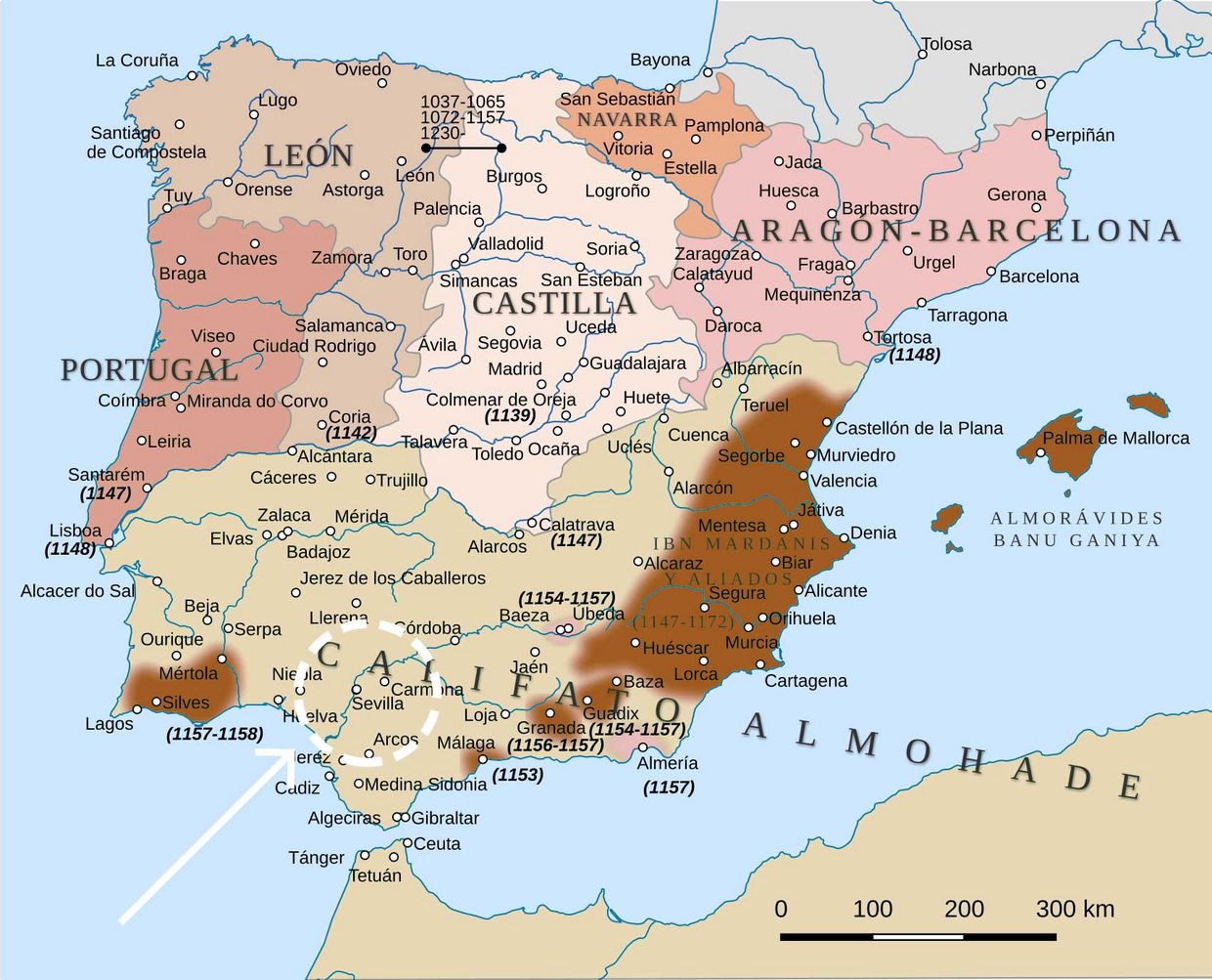

King Ferdinand III of Castile and Muslim Spain

Islam spread quickly from the Middle East along North Africa by the late 7th century CE. In 711 Berber forces invaded the Iberian Peninsula across the Straits of Gibraltar, capitalising on internal strife within the Visigothic hierarchy, and established Arab Muslim rule throughout most of Iberia. The territories under Muslim rule were known as al-Andalus, from which the present-day autonomous region of Andalusia derives its name. By the 12th-13th centuries, these territories covered only the southern half of the Peninsula but formed part of the Caliphate of the Almohad dynasty which also held power in Morocco. Meanwhile, several Christian kingdoms had emerged to the North.

King Ferdinand III of Castile (1199/1201–1252) conquered the Almohad capital Seville in 1248. After its fall, only Granada remained as the last Muslim kingdom of al-Andalus, until its conquest by the Christians in 1492. During the “Convivencia” of the intervening centuries, Jews, Muslims and Christians co-existed in society.

Ferdinand III was buried in Seville Cathedral, where his remains were venerated. He was described as a saintly as well as a warlike king by the medieval chroniclers. By the early 17th century, the case for his canonization was actively promoted by both the Spanish church and the monarchy under Philip IV. It was set out by Juan de Pineda in Memorial de la Excelente Santidad y Heroycas Virtudes del Señor Rey Don Fernando, Tercero deste Nombre … (Seville, 1627). The cult of Ferdinand III was granted by Pope Clement X in 1671.

In the context of Counter Reformation, it was also important to establish an orthodox visual image of Ferdinand. Thus, it became standard to depict him with the regalia of kingship, such as crown and/or orb and ermine robe, along with the attributes of warrior – armour and sword.

Stirling praised the volume as “one of the most beautiful books of Spanish local history” in his own book on Spanish art, Annals of the Artists of Spain, published in 1848.3

Learn more about Stirling’s Annals

The Annals of the Artists of Spain (London, 1848)

William Stirling’s book, consisting of three volumes of text and a limited-edition volume of photographs, was the first scholarly history of Spanish art in English. Its comprehensive range of artists, which included sculptors, goldsmiths and printmakers as well as painters, owed much to Spanish sources, notably Ceán Bermúdez’s Diccionario histórico de los más ilustres profesores de las bellas artes en España, 6 vols. (Madrid, 1800). However, it was the first chronological history of Spanish art and also provided social, political, religious and cultural context. In addition, Stirling drew on his own experience of visiting Spain, as well as museums and private collections throughout Britain and elsewhere in Europe. Festivities such as the St Ferdinand celebrations were covered both as artistic events and for the quality of the prints in the festival books recording them.

Talbotype Illustrations to the Annals of the Artists of Spain (1847–48)

The volume of photographs that accompanied the text made the Annals the first photographically illustrated book on art history. Photographing artworks using the newly invented technique was challenging and many of the photographs were of prints. It included the etching of Murillo’s “true portrait” (vera effigies) of St Ferdinand from the Fiestas de Sevilla. Stirling valued this as “probably the first print ever made from a work of Murillo”. 4.

Links to these publications

Annals v. 1 | Annals v. 2 | Annals v. 3 | Ceán Diccionario | Talbotypes volume

Stirling Maxwell in Seville

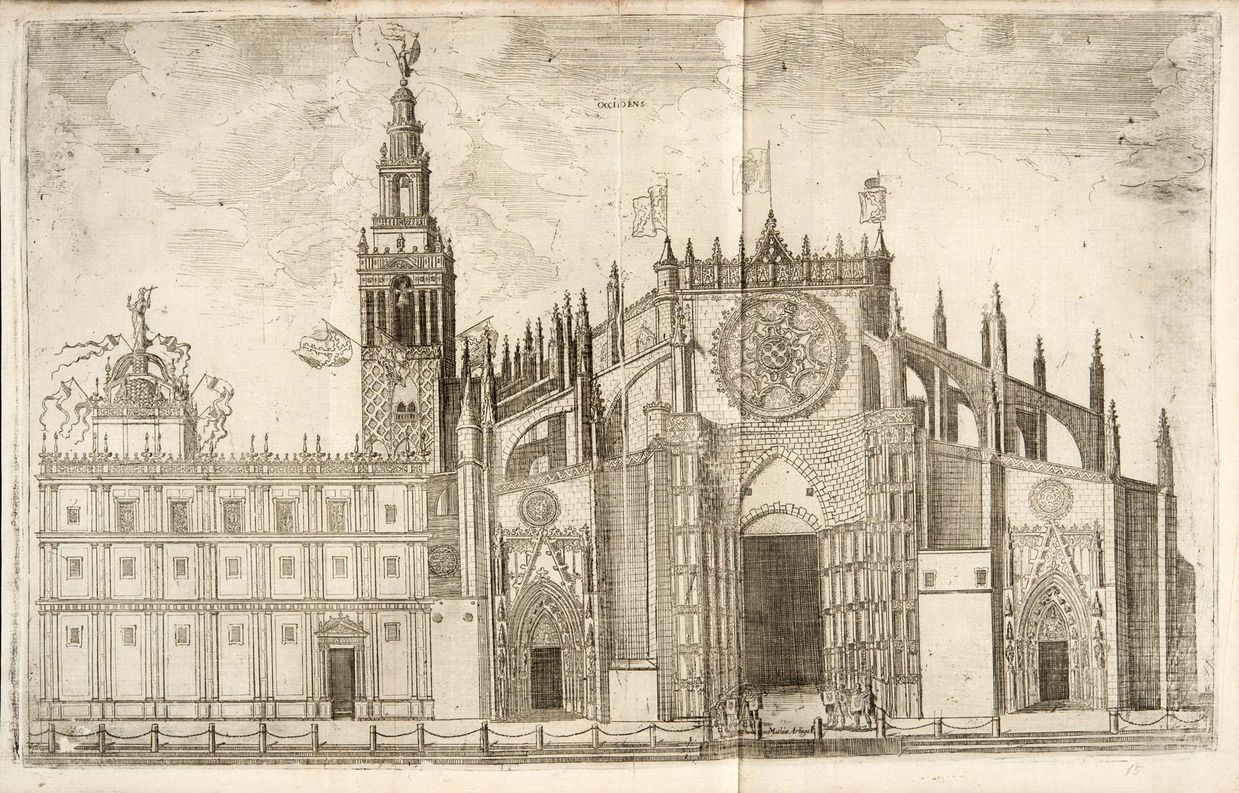

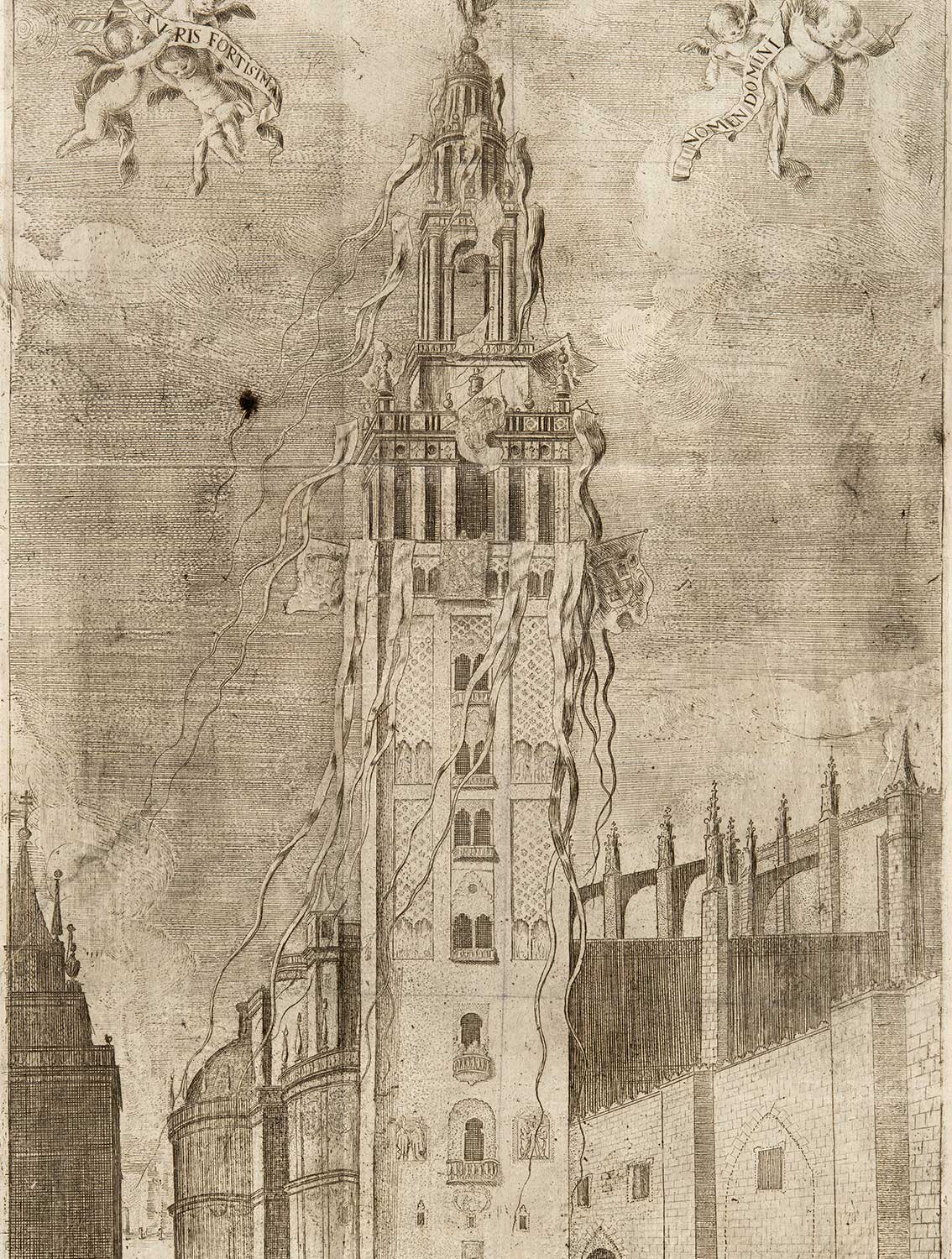

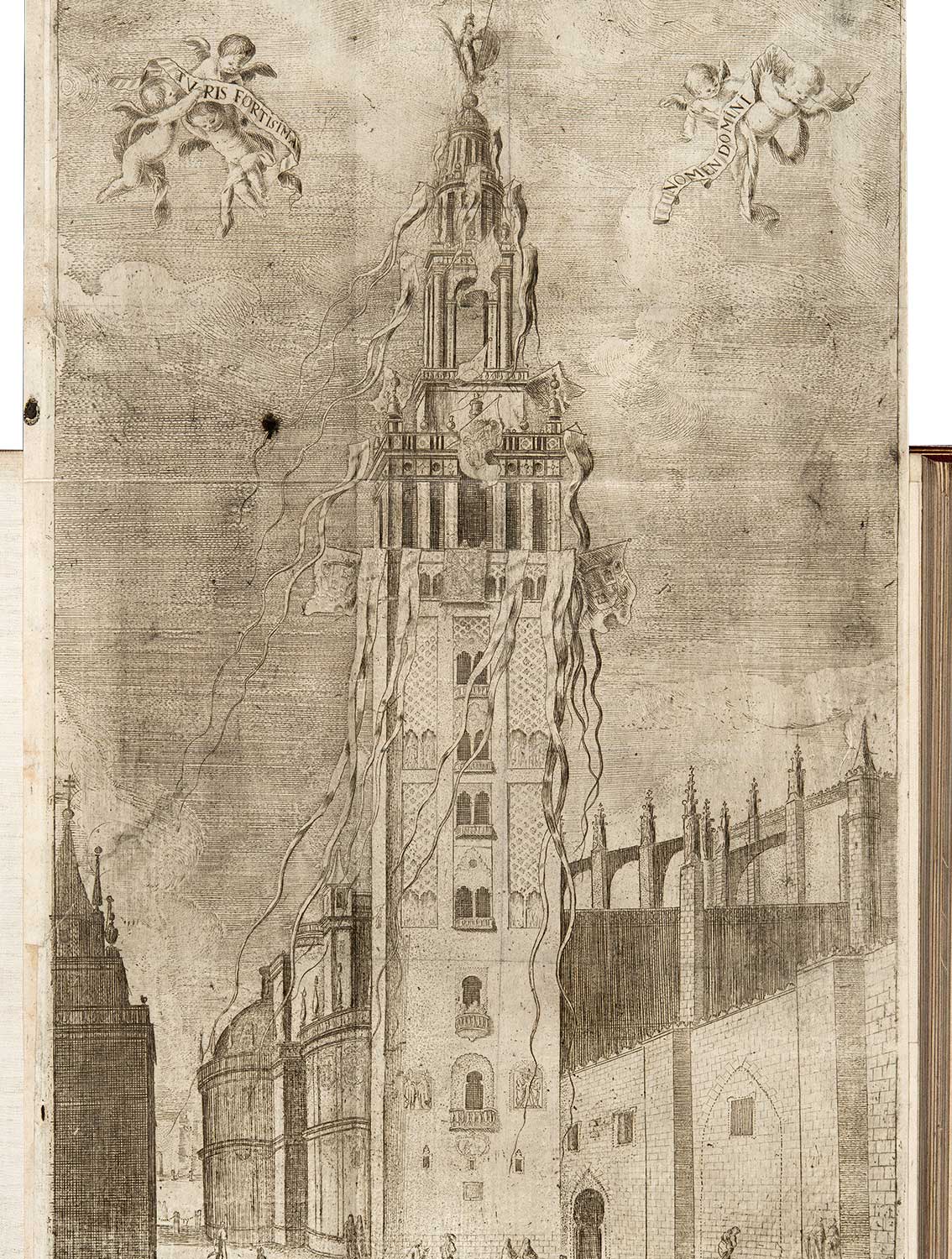

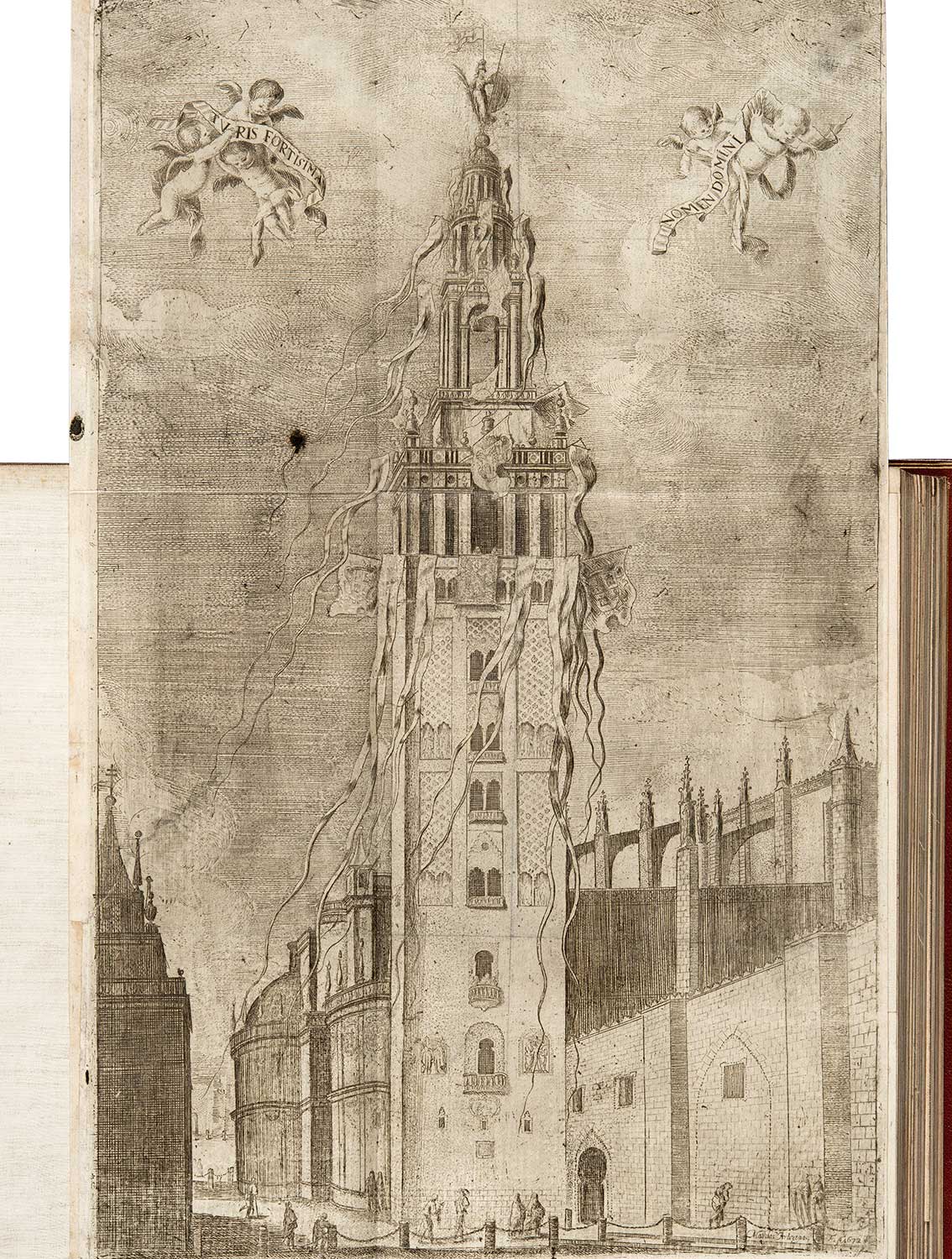

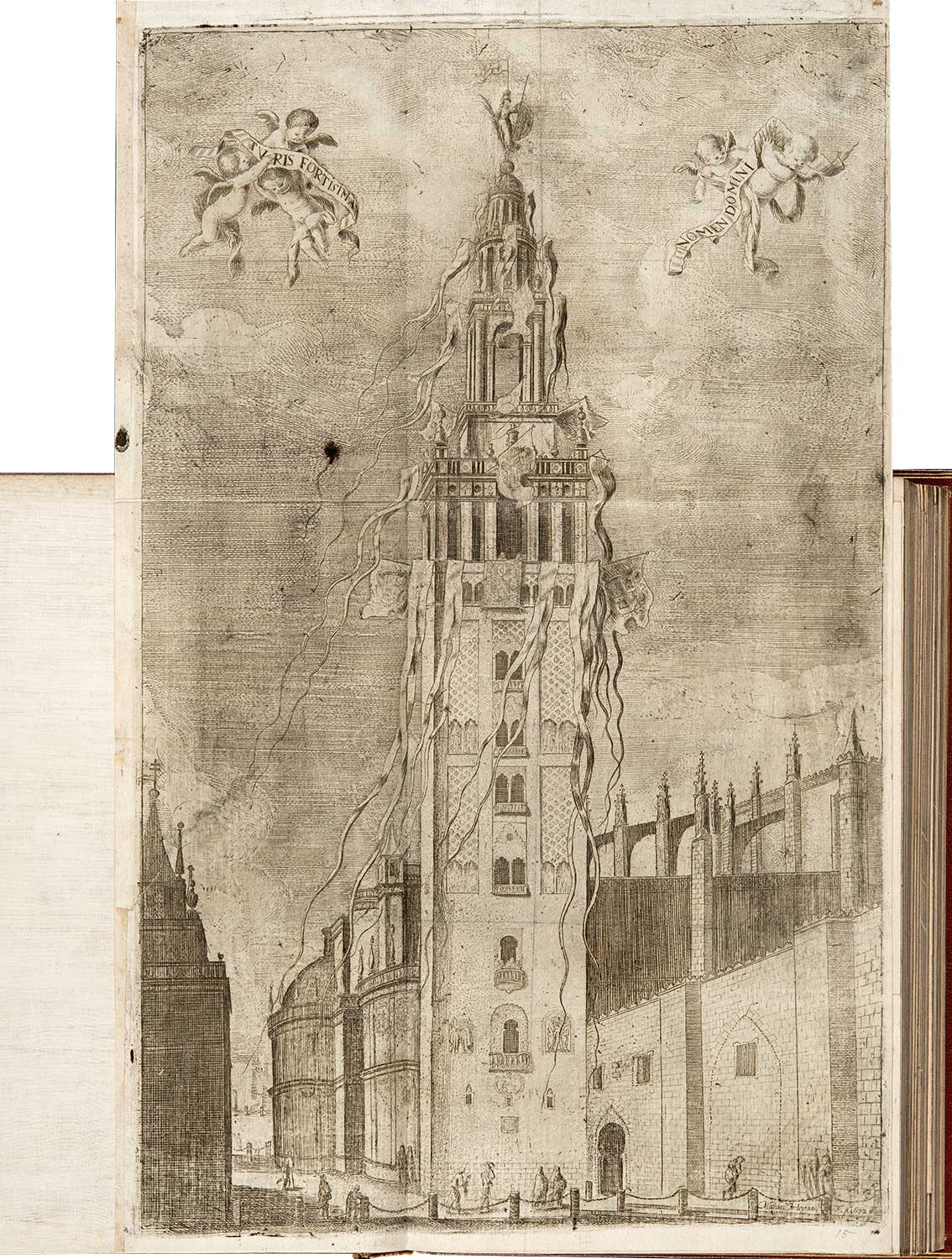

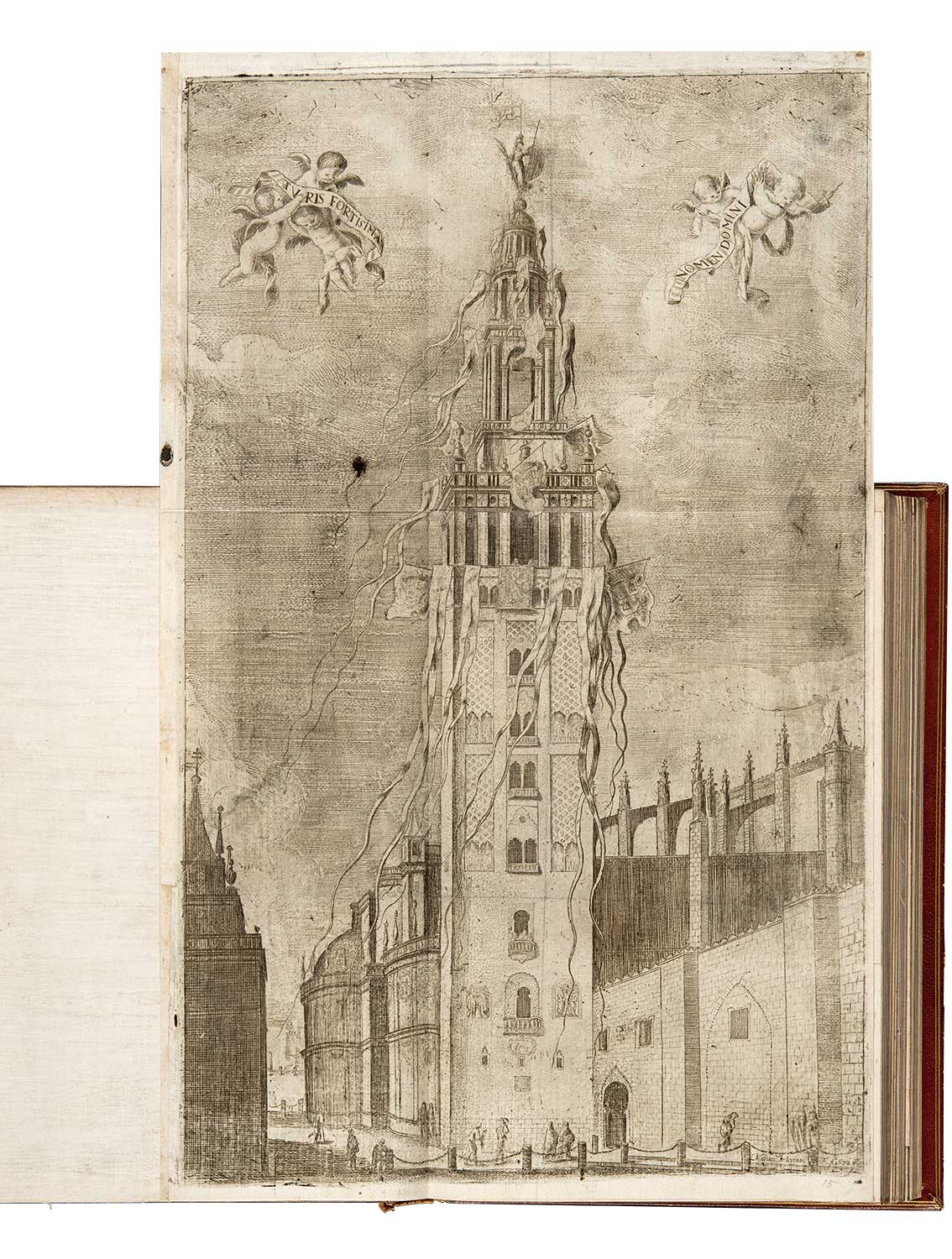

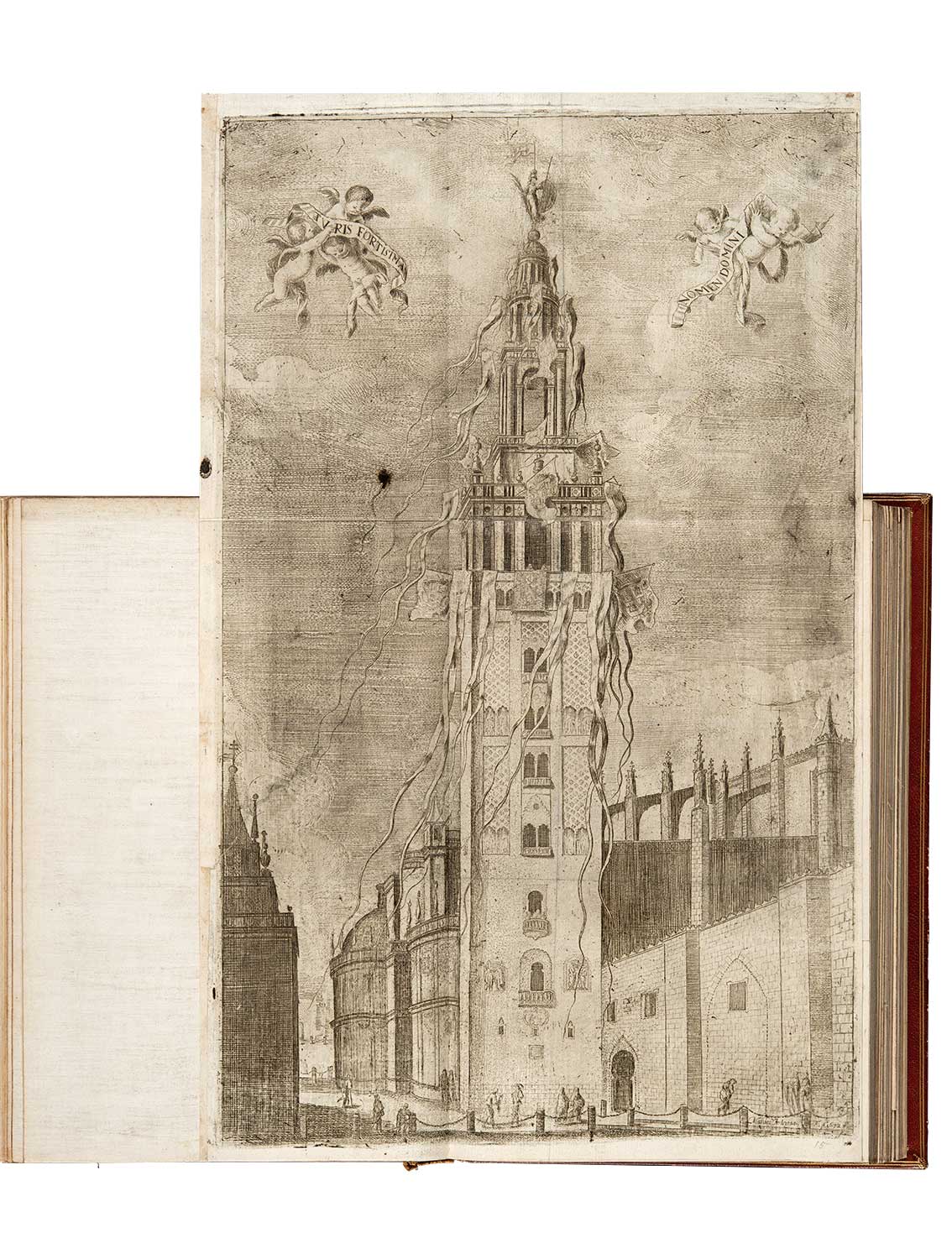

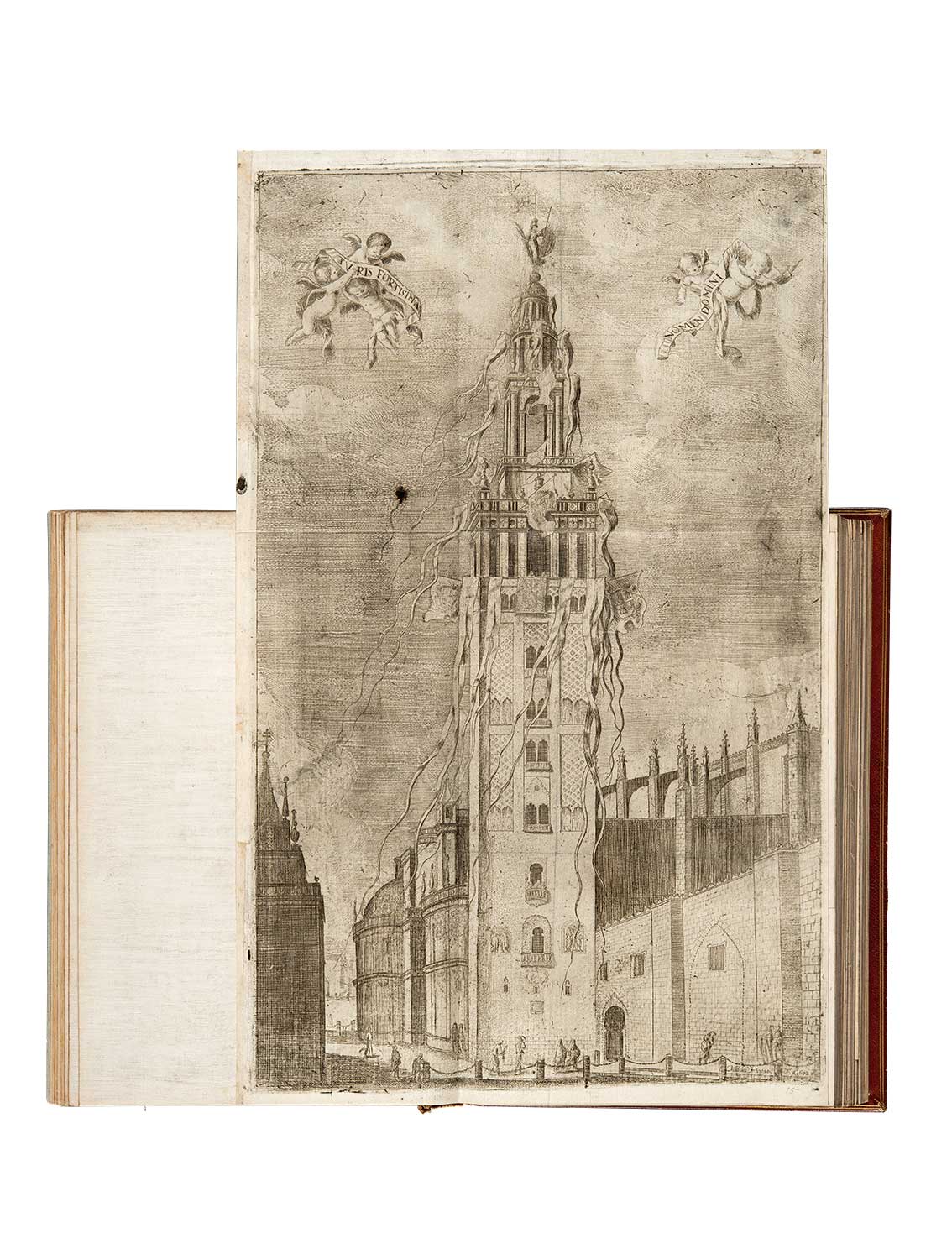

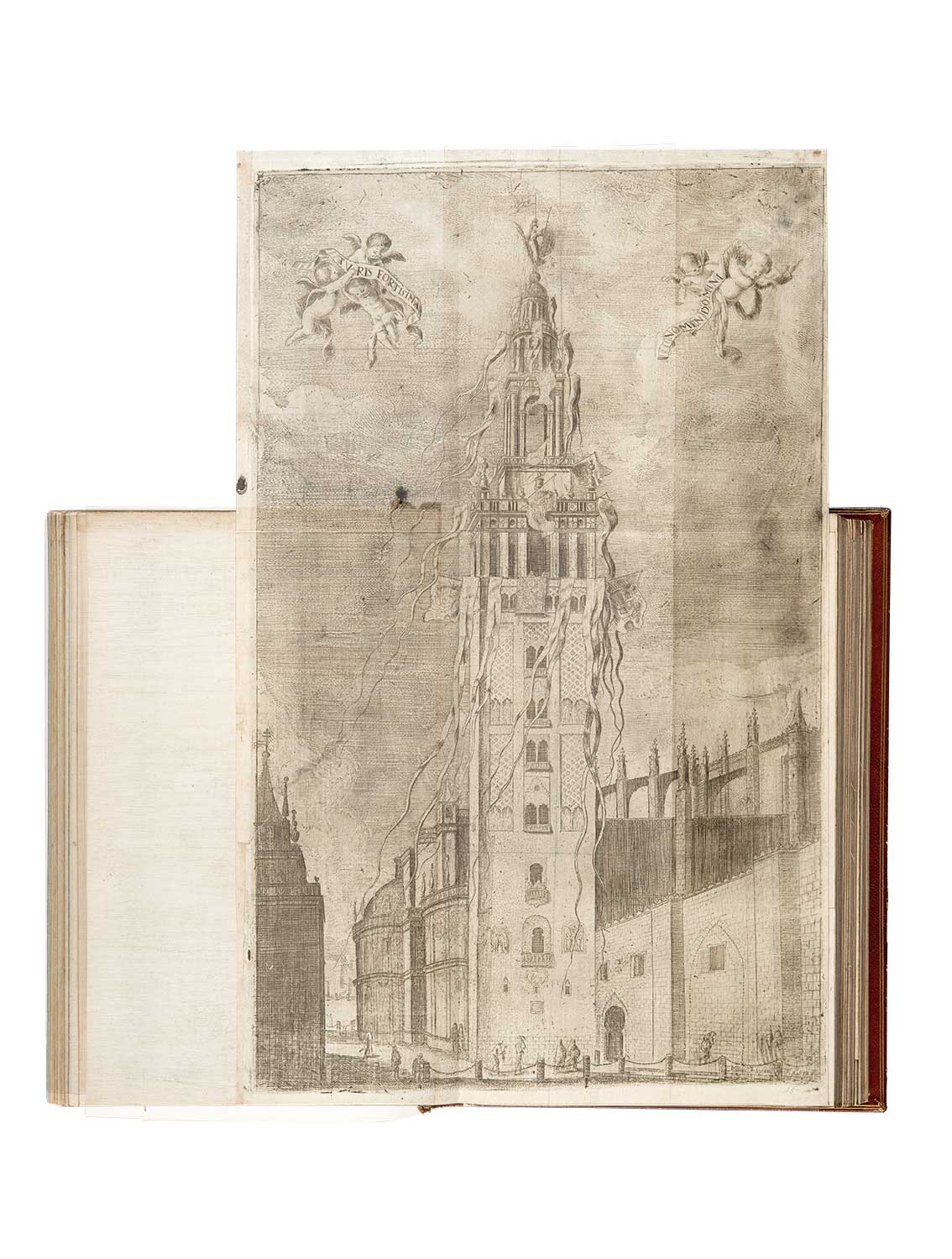

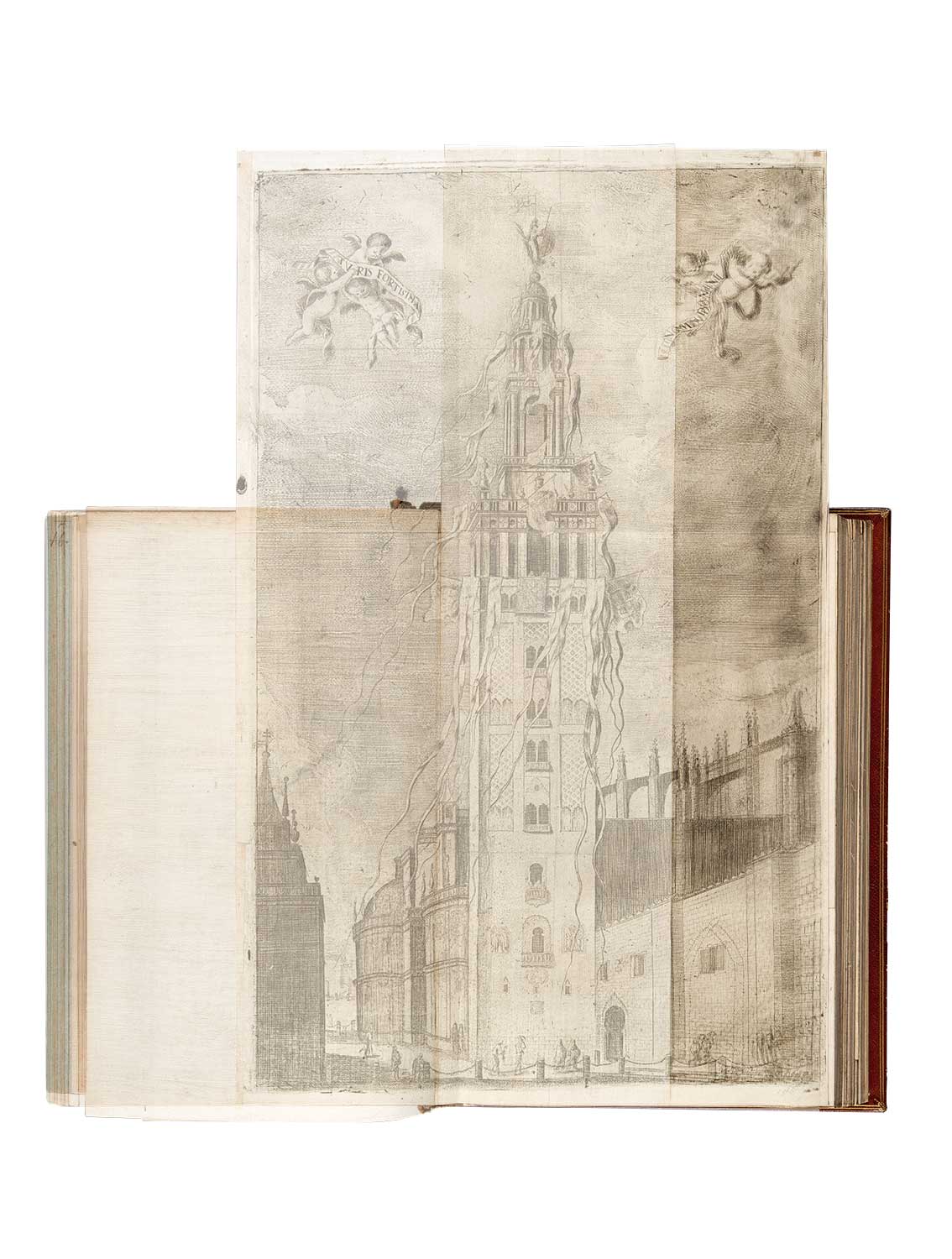

Stirling Maxwell himself visited Seville for the first time in 1841, soon after the city became the focus of an international art tourism boom. He praised its Cathedral as “the finest Gothic Church in the world”, above which “the Giralda or Moorish belfry soars into the sky […] rich with the most elaborate tracery”. 5

Stirling had already seen and admired views of the Cathedral and the Giralda by the Scottish artist David Roberts, who visited Seville in the 1830s.

Find out more about Seville Cathedral and the Giralda

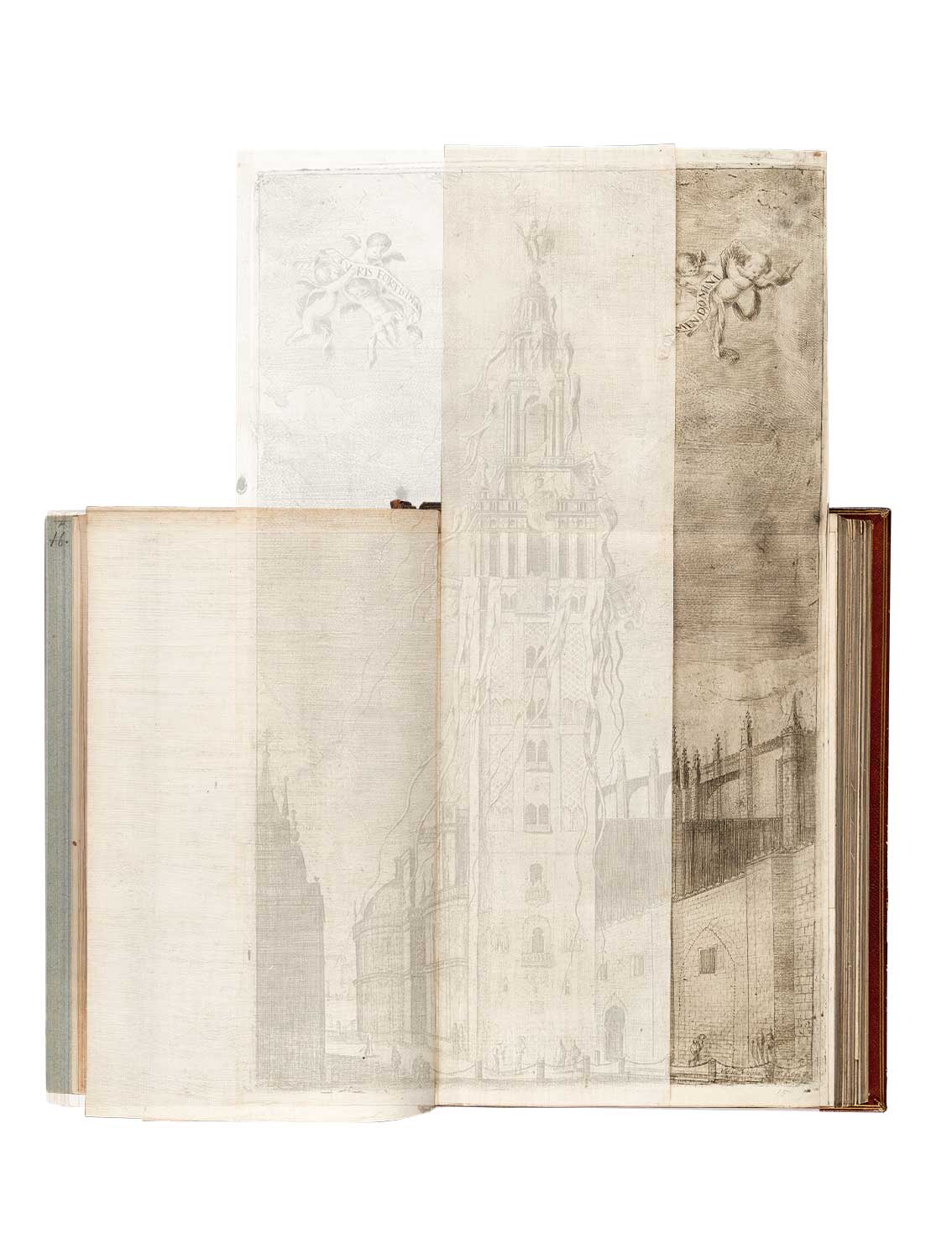

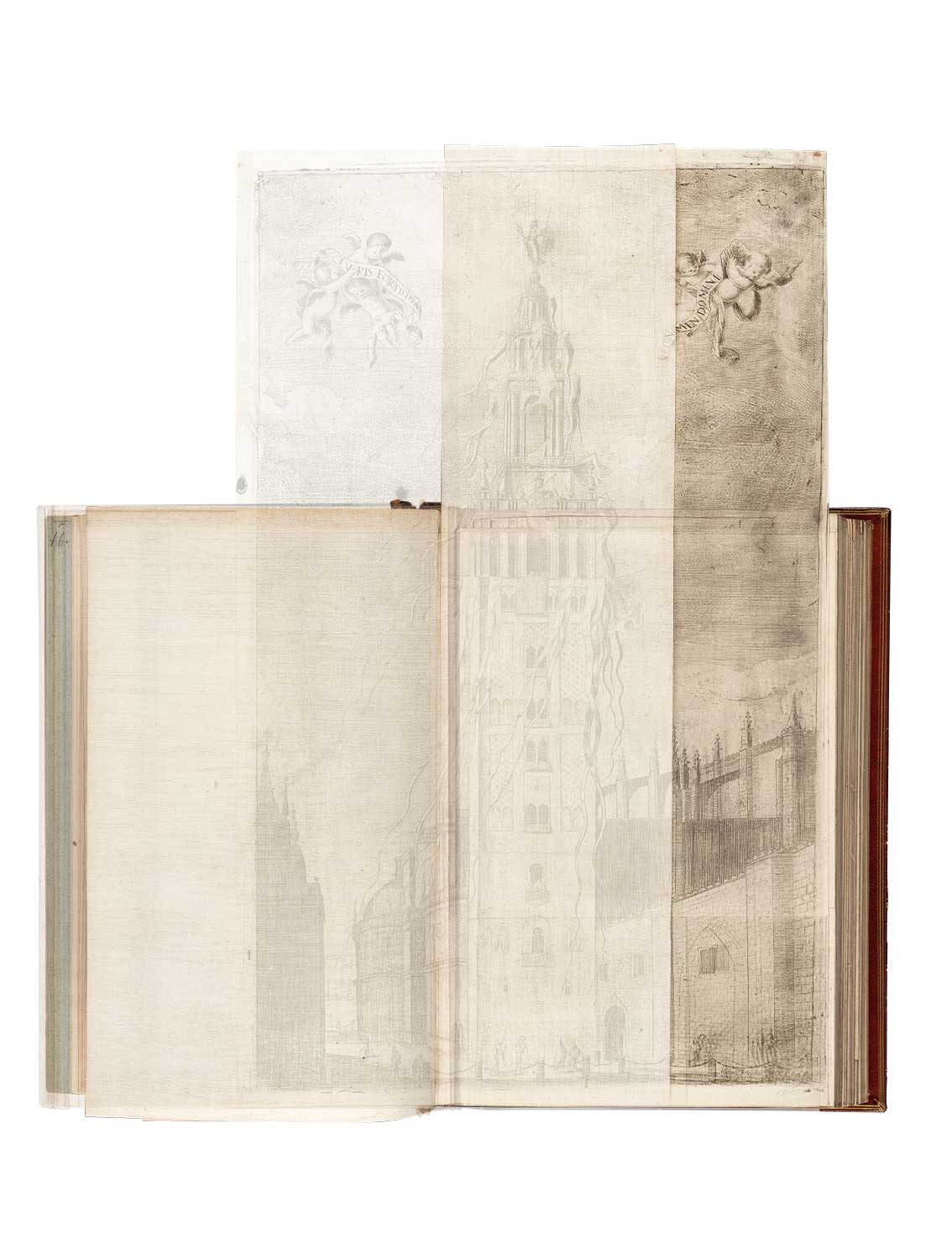

The illustration shows the mixture of styles, from the brick and stone of the Giralda minaret and belfry in the centre, to the buttressed Gothic cathedral to the right. To the left is the more classical repertoire of the Church of the Sagrario, which had only recently been completed. Its cupola, shown here draped for the festivities, was later altered and the figure of Faith on top replaced by a cross. Seville Cathedral, built between 1402 and 1506, is the largest Gothic cathedral in the world. The main core owes much to French Gothic style and masters. Additions and alterations continued to be made by Spanish architects in the classically-inspired styles of the Renaissance and the Baroque in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Like many cathedrals in Spain, it was erected on the site of the former Great Mosque, in this case one that had been designed for the 12th-century Almohad dynasty. The Giralda tower is a unique survival, which likewise originally dates from the 12th century and served as the minaret of the mosque. Constructed in stone and decorative brickwork, its additional storeys were built in the 16th century by Hernán Ruiz the Younger to house the Cathedral bells. It is topped by the Giraldillo weathervane, a bronze figure of Faith (La Fé), which was added soon after.

THE FIESTAS IN TEXT AND IMAGE

The text of the Fiestas, by Fernando de la Torre Farfán, one of the canons of Seville Cathedral, describes in detail the special decorations for the celebrations, which were produced by leading Seville artists, including Valdés Leal, Simón Pineda, Pedro Roldán and Murillo.

Some of the illustrations were beautiful – and fragile – large-format etchings, like this one by Matías de Arteaga, which shows the Giralda decorated with streamers and flags. It is one of eight folding plates which were inserted in the book.

Learn more about these artists

Seville’s artists and the Fiestas de Sevilla

The leading artists of the day in Seville were involved in preparing the decorations. Chief among them was the painter Juan de Valdés Leal (1622–1690), in collaboration with the designer Bernardo Simón de Pineda (1638–c. 1702) and the sculptor Pedro Roldán (1624–1699). Perhaps Valdés Leal and Simón de Pineda are represented by the figures discussing the plans and directing the measurement in the plate of El Triunfo.

Francisco de Herrera the Younger (1627–1685) was also involved. As well as the title-page, he also designed the dedication page to King Charles II of Spain. Bartolomé Esteban Murillo (1617–1682) likewise played a part, not only as painter of the likeness of St Ferdinand, but he also designed the decorations for the Church of the Sagrario adjoining the Cathedral. All these artists were involved in the historic but short-lived Seville Academy, founded in 1660, the first art academy in Spain for which records are held. Murillo and Valdés Leal were its first Joint Presidents.

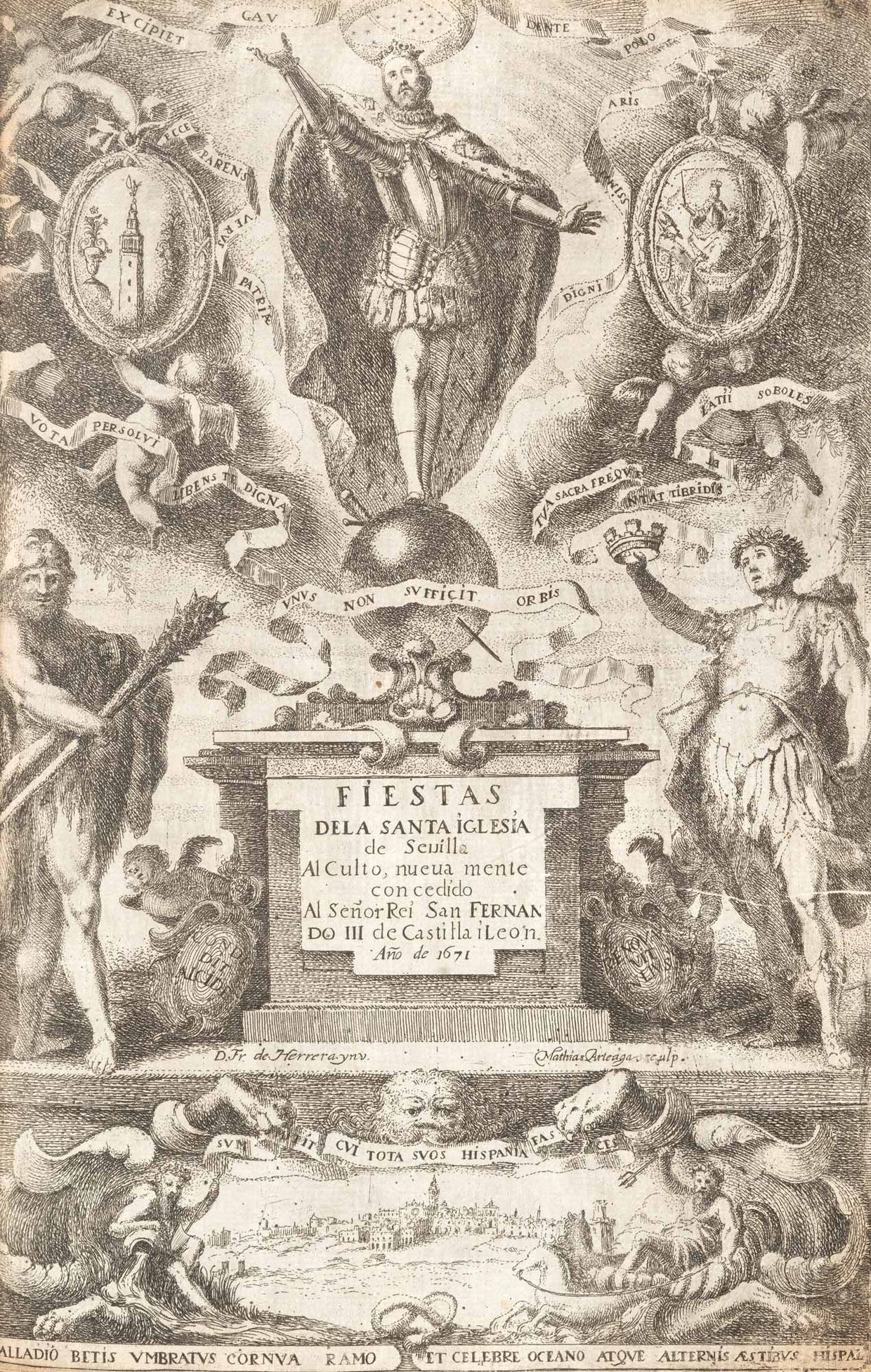

The Title-page

The illustrated title-page, designed by Francisco de Herrera the Younger and etched by Matías de Arteaga, shows Ferdinand as conqueror of Seville with, on either side of the title, Hercules, on the left, the mythical founder of the city and, on the right, Julius Caesar, to whom Seville’s Roman foundation was attributed. Below is an illustration of the city. The design is enriched with allegorical and symbolic details which all serve to promote 17th-century notions of the city’s history and Ferdinand’s significance within it.

El Triunfo

Another of the folding plates shows the towering Baroque main monument, El Triunfo, which was erected inside the Cathedral for the celebrations. The decoration of the monument involved collaboration in many different fields: – sculptures and paintings, as well as emblems and inscriptions.

The Ground Plan

In this plan of the Cathedral the position of El Triunfo is indicated between the four pillars at the western end of the central nave of the Cathedral, opposite the Main Doorway.

Torre Farfán explained that this site was chosen to take advantage of the natural light from the open door. 9

The scale of the ground plan and the overall dimensions of the Cathedral are shown at the bottom of the plate.

El Triunfo monument

Detail of the position of El Triunfo monument (42), opposite the Main Doorway leading to the Cathedral steps (“Puerta Principal que sale á gradas”).

Scale

The scale, in Spanish or Castilian feet (pies), shows the width of the Cathedral as just over 290 feet or 80.80 m. Overall length is given as 379 feet (105.60 m) and height as 217 feet (60.46 m). [1 pie = 0.278 m. 1 m = 3.588 pies.]

The Main Doorway of the Cathedral and the daylight coming in from the street outside is shown in another of the folding plates signed by Valdés Leal.

Through the open door, we can glimpse the preparations made for the procession that would extend the celebrations into the streets surrounding of the Cathedral. The buildings and balconies opposite the doorway are hung with fine cloths. 10

People are already taking their seats to watch. According to Torre Farfán, it was as if the pomp was so magnificent that it could no longer be contained in the temple and spilled out its fruitfulness and wealth. 11

The Procession

The highlight of the procession was another image of Ferdinand as conquering king, his eyes cast heavenward, dressed in ermine and brocade and glittering with jewels, gold and silver. Torre Farfán claimed that the appearance of this “Sovereign Effigy on the ancient, welcoming streets moved the crowd so much that it seemed as if their clamour would burst the upper spheres of the heavens”. 12

Like the image on top of the main monument, it was also made by Pedro Roldán for the celebrations, and is still used today in the annual Corpus Christi processions at the Cathedral.

The procession continues to take place to celebrate Corpus Christi each year in May or June (depending on the date of Easter). Nowadays, most people use their cameras and phones to make their own records of celebrations like this.

Torre Farfán’s Book Today

Books such as Torre Farfán’s Fiestas de Sevilla, which were collected by Stirling Maxwell, are important sources in helping us to understand what festivals were like in the past and how they have influenced the vibrant street theatre and spectacular celebrations that continue to define many people’s image of cities like Seville today. Over the centuries, these festivals and the historic events they commemorate have also contributed to self-perceptions of identity for many inhabitants.

Further Reading

Al-Andalus: The Art of Islamic Spain, ed. Jerrilynn Dodds (New York: Harry Abrams, 1992)

Antonio Bonet Correa, “Torre Farfán y la fiesta de la canonización de San Fernando en Sevilla, en 1671”, in Fernando de la Torre Farfán, Fiestas de la S. Iglesia metropolitana y patriarcal de Sevilla, al nuevo culto del Señor rey D. Fernando el Tercero de Castilla y de Leon, facsimile edition (Seville: Fundación FOCUS, 1985)

La catedral gótica de Sevilla: fundación y fábrica de la obra nueva, ed. Alfonso Jiménez Martín (Seville: Secretariado de Publicaciones de la Universidad de Sevilla, 2006)

Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez, Descripción artística de la catedral de Sevilla (Seville: Viuda de Hidalgo y Sobrino, 1804) https://play.google.com/books/reader?id=kOlZAAAAYAAJ&hl=en_GB&pg=GBS.RA1-PA1

Richard Hitchcock, Muslim Spain Reconsidered from 711 to 1502 (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2014)

Alfonso Jiménez Martín, “La planta de la mezquita almohade de Sevilla”, Boletín de la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de Nuestra Señora de las Angustias de Granada, 12 (2005), 50-87 https://www.academia.edu/8982578/_La_planta_de_la_mezquita_almohade_de_Sevilla_Bolet%C3%ADn_de_la_Real_Academia_de_Bellas_Artes_de_Nuestra_Se%C3%B1ora_de_las_Angustias_de_Granada_12_2005_50_87

Hilary Macartney, “Lingering over Graphic Descriptions of Grand State Ceremonials and Festivities: Stirling Maxwell and the Role of the Artist in Golden-Age Spain”, in Bulletin of Spanish Visual Studies, 3:2 (2019), Special Issue: Teatralidad y performatividad de las artes: el contexto hispánico en la Europa de los siglos XVI–XVIII, ed. Carmen González-Román & Hilary Macartney, 189-204

Rosemarie Mulcahy, “Celebrating Sainthood, Government and Seville: The Fiestas for the Canonization of King Ferdinand III”, Hispanic Research Journal, 11:5 (2010), 393-414

Fernando de la Torre Farfán, Fiestas de la S. Iglesia metropolitana y patriarcal de Sevilla, al nuevo culto del Señor rey D. Fernando el Tercero de Castilla y de Leon (Seville: Viuda de Nicolás Rodríguez, 1671 [1672]).