A Short Stroll on the Paseo del Prado in Madrid in the 17th Century

Stage, Scenography and the Court

Concepción Lopezosa Aparicio

El Prado: Urban Enclave and Scenery

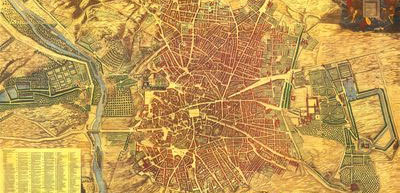

After the establishment of the court in Madrid in 1561, the eastern boundary of the city became the main access point to the population and the start of the route followed by the royal procession between the Camino de Alcalá and the Royal Alcázar, the monarchs’ official residence.

Consequently, the well-known Paseo del Prado, the enclave that ran between the Calle de Alcalá and the Carrera de San Jerónimo, became an area of sociability par excellence of the town and the setting for the most notable institutional events and daily experiences. The Paseo del Prado became an authentic urban theatre, an emblem of the city and an integral part of the city’s memory.

The Camino de Alcalá

The city and the court of Madrid from the Camino de Alcalá. The walls of the Retiro, the Puerta de Alcalá and the monastery of Las Salesas Reales can be seen.

Royal Alcázar of Madrid

The old Muslim Citadel became the residence of the monarchs, after the establishment of the capital in Madrid in 1561. The building, transformed during the seventeenth century to adapt it to the needs of the Habsburg monarchy, was reduced to rubble after a fire in 1734.

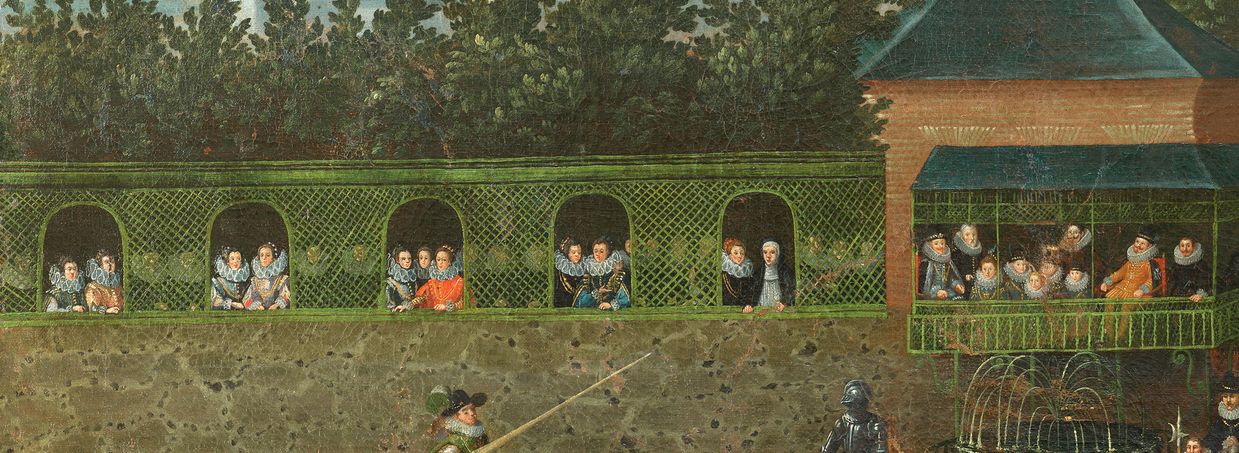

Paseo del Prado: Theatre of Memory

This view of the Paseo del Prado at its confluence with the Carrera de San Jerónimo, the main access road to the city, shows the different forms and possibilities of occupation and the use of the outskirts of Madrid at the beginning of the 17th century. Note the watchful eyes of the spectators located in the lookouts of the Garden House of the Duke of Lerma.

Music Turret

Music was, since the end of the sixteenth century, a constant in the Paseo del Prado, due to the qualities of the area as a meeting spot and as the main area of sociability.

The wooden planks periodically arranged on the promenade to accommodate musicians were replaced in 1612 by a sturdier building for Minstrels were professional musicians at the service of the city council who entertained passerby with their sonatas. They were specialized in wind instruments, mainly shawms, sackbuts, cornets and flutes. The musical programmes the minstrels put on were further developed and elaborated for institutional events that took place in the area.minstrels to offer their repertoires according to a schedule of performances determined by the municipality.

The turret, located in front of Lerma's orchard, became a common point of

reference in the area, and its surroundings served as backdrop for life during the Spanish Golden Age.

The building was demolished in the mid-eighteenth century, due to an urbanization project undertaken in the area at the request of Charles III of Spain.

For the occasion of Queen Margaret of Austria’s entrance into the city, the turret was transformed into the ‘tower of joy’ and used to entertain the Queen.

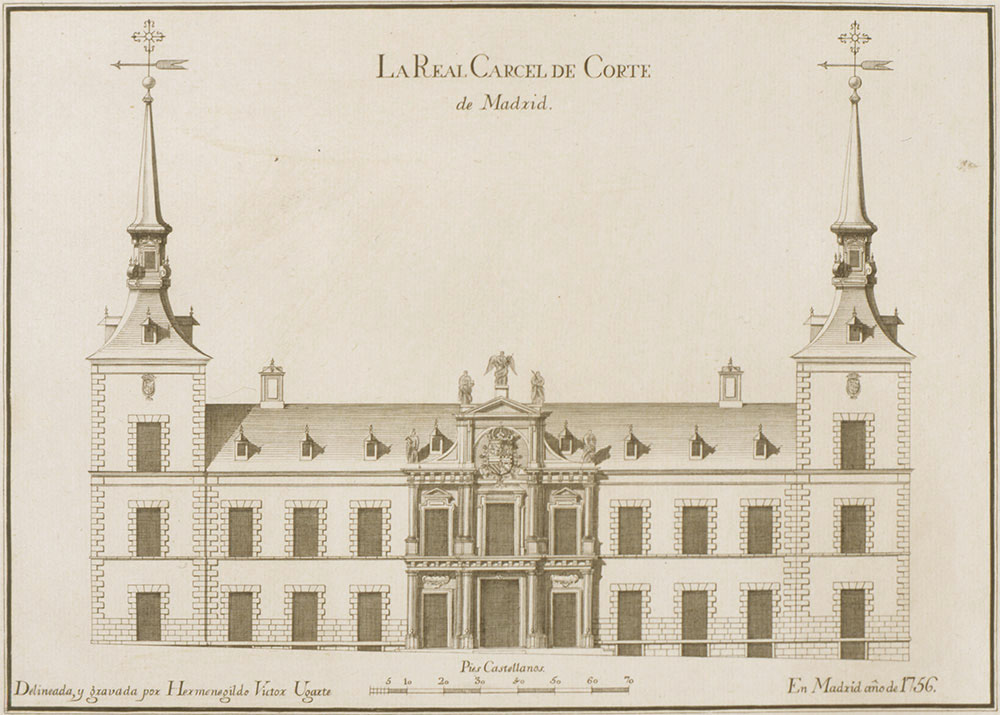

The architectural qualities of the turret

Brick structures covered with slate spire were in tune with the features of the Baroque style that characterized Madrid and its physiognomy throughout the seventeenth century as it developed into the capital.

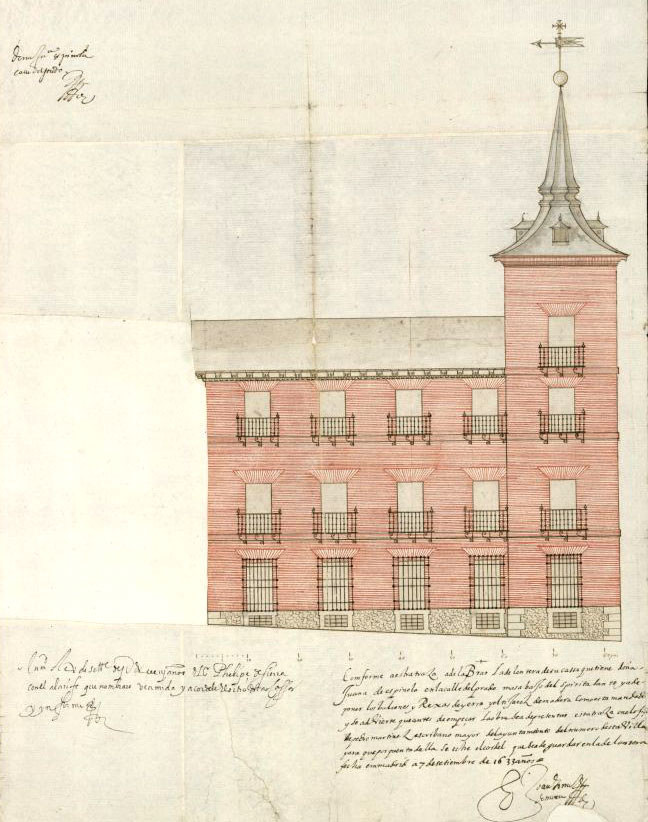

Juan Gómez de Mora

House of Juana Spínola on the Prado, 1633.

Archive of the City of Madrid.

Hermenegildo Ugarte y Gascón

View of the Court Prison, 1756

Museum of History of Madrid

Sociability: Women in El Prado

Within the social sphere, relations between both sexes gained special prominence in this enclave of the city that was prone to courtship and romantic pursuits. Women had a constant presence on the promenade, and their social position favoured different ways of navagating public space. Women from the most select environments were regulars in El Prado.

“Las damas, el día de fiesta, van al prado de San Jerónimo que figura entre las cosas más célebres de Madrid”

“On holidays, women go to the field in San Jerónimo, which is among the most famous attractions in Madrid”

In contrast to accepted forms of socialization, the Prado was also an environment susceptible to inappropriate practices such as prostitution. Women of scarce resources practiced prostitution in the unpopulated areas of the promenade, while the main avenues

worked as a walkway for the prostitutes of higher level, who were recognizable by their particular behaviour and style of dress. The presence of tapadas (veiled women) was common on other promenades and public spaces such as the Alameda de Hércules in Seville.

“… no me faltó proporción para ver a los caballeros y damas de España sobre todo en un lugar de árboles o bosques que llaman Prado, donde va toda la sociedad elegante para hacer allí sus reuniones…”

“… I did not fail to see the gentlemen and ladies of Spain especially in a place of trees or forests that they call Prado, where the elegant society usually meets…”

“Van con velos negros y los repliegues sobre el rostro, no dejando al descubierto más que un ojo. Hablan a la gente con descaro, y se las encuentra tan impúdicas como disolutas”

“They wear black veils and folds on the face, exposing not more than an eye. They speak to people with impudence, and they are as insolent as dissolute”

Sociability. The Use of the Carriage

From the beginning of the 17th century, the horse carriage became a symbol of distinction, generating new forms of behaviour in the city. It was very common to access El Prado by carriage, which resulted in the creation of the first traffic regulations in the city.

Women were immediately aware of the possibilities of the coach, which allowed them to project their privacy into the public sphere without renouncing intimacy entirely. The carriage was a sought after object both as a reference of status and as a guarantor of autonomy, functioning as a balcony on wheels.

Convent of Trinitarios in the Duke's orchard

In 1606 the Duke of Lerma, protector of the Trinitarian Reformation, founded the convent of the Barefoot Trinitarians, under the invocation of Our Lady of the Incarnation, transferring part of the lands of his garden for that purpose.

The gardens

The gardens occupied a considerable part of the property. They extended between the nucleus of the house and the convent of the Trinitarians. The gardens, that reached El Prado, were structured on different levels, with specific designations, such as Garden of Hercules or Garden of Eve. They were decorated with sculptures, numerous plant species and fountains that gave splendor to the site. Moreover there was a zoo with exotic animals and a bullring, the first that was built in the Villa.

The main rooms

The construction of the residence started in 1614 according to a plan drawn up by the royal architect, Juan Gómez de Mora. The private house, with its façade opposite the Carrera de San Jerónimo, was organized around a square patio off of which the main rooms were arranged. The accessory buildings, structured around small patios, integrated numerous complementary rooms including kitchens, barns, sheds, offices, infirmaries and stables that rivaled those of the monarch.

Passageway to San Antonio del Prado

In 1609 the Duke of Lerma founded the Capuchin Convent of San Antonio de Padua within the limits of his property next to Carrera de San Jerónimo. As the painting shows, the convent enclosure was linked to the Duke's Garden House through a raised passageway, which allowed him to communicate directly with the religious order as well as with the convent of Santa Catalina de Sena, the third of the religious foundations that were authorised to be built on the grounds of the Duke's property.

The Garden House of the Duke of Lerma

The Garden House was the first noble residence in the old Prado and built at the request of Don Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas, Duke of Lerma.

Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas, 5th Marquis of Denia and 1st Duke of Lerma (1553-1625) was a favourite and adviser of Philip III of Spain between 1598 and 1621, becoming the most powerful man of the court at the time.

Pedro Pablo Rubens

Don Francisco de Sandoval y Rojas. Duke of Lerma.

Madrid, Museo del Prado

It aimed at creating a courtly environment as an emblem of prestige and personal power and as a place for the distraction of the monarch—an extension of the royal residence. The land acquired by the Duke allowed him to create a residential complex composed of a few main buildings with access to the Carrera de San Jerónimo, secondary rooms, large gardens overlooking the Prado and the conventual enclosures of Trinitarios, Santa Clara and San Antonio.

The complex imitated the plan of his ducal villa of Lerma – the greatest expression of his power – on a smaller scale. The architect Juan Gómez de Mora (1586-1648) was commissioned to carry out the vision of the Duke of Lerma.

The Lookouts of Lerma's Orchard

Having a gallery overlooking the Prado was a great novelty and illustrated the uniqueness of the Lerma residence. The Duke made sure he had a a balcony in this fundamental part of the city, namely the place where the first arch was erected to signify the official itinerary of the Royal Gates, the spot where the municipal authorities handed over the keys of the city to illustrious visitors.

The lookouts were also a perfect platform for witnessing the festivities promoted by the Duke in the forefront of the garden and to participate in the daily life that took place in the area.

It was a simple structure, like a gallery, running along the front of the promenade and composed of a series of open windows, with an emphasis on the corner lookout.

The balconies of the garden of Lerma had a direct impact on the lookouts of the Buen Retiro Palace

The new royal residence built from 1630 at the request of Count Duque de Olivares was located opposite the house of Lerma.

The galleries of the palace were designed as a structure independent from the building, in the guise of a threare box, on the corner of Camino de Alcalá and El Prado, a privileged point at the main gate to the city, dominating the front of the promenade.

Ordinary Life

Water, flowers, fruit and sweets were products often demanded by walkers in El Prado, generating an outstanding commercial activity which needed to be regulated by the municipal authorities in order to curb illegal practices, avoid abusive prices and resolve conflicts with merchants who saw a clear competition with their own businesses.

The presence of water carriers in charge of the itinerant water supply, such as the famous waterseller of Seville who was immortalized by Velázquez, was a constant in modern cities. They were especially visible in the promenade due to the high demand and due to the numerous fountains in the area offering a constant supply for refilling.

Regarding sales, women were usually in charge of running the commercial activity that emerged in this area.

Marginality

The continuous influx of people to the promenade also included vulnerable groups on the margins of society who exercised begging to get alms.

With visible class differences, conflicts associated with inappropriate behaviour that ended in frequent fights and disagreements were common.

Festivities. Tournaments and Games

The orchard of the Duke of Lerma became the usual backdrop for the celebration of court holidays. These festivities served as entertainment for the king and his court, as well as for the public exhibition of the Duke's power.

The Paseo del Prado, opposite Lerma's garden, acted as an extension of the Duke’s orchard and setting for the main festive events. The lookouts provided a privileged view to frequent tournaments, quintains and ring joustings that took place regularly between 1608 and 1618.

Bibliography

Alfredo Alvar Ezquerra, El Embajador Imperial Hans Khevenhüuller (1538–1606) en España, Madrid, Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación, 2015

Candela Argüello del Canto, “Las tapadas”. Una propuesta sobre la representación de la prostitución en la pintura del Siglo de Oro”, BSAA Arte, 83 (2017), 235-252. As found at: www.researchgate.net/publication/321223262_

Dolores Brandis García, “La construcción y difusión de las imágenes del Prado de Madrid en los relatos de viaje”, Espacios y destinos turísticos en tiempos de globalización y crisis. AGE, Madrid, 2011, 169-185. As found at: https://e-archivo.uc3m.es/bitstream/handle/10016/16462/construccion_brandis_TERAP_2011.pdf?sequence=1

Bernardo García García, “Los espacios de la privanza. Las residencias del favorito como extensión de los Reales Sitios en tiempos del duque de Lerma”, in: Felix Austria. Lazos familiares, cultura política y mecenazgo artístico entre las cortes de los Habsburgo. Fundación Carlos de Amberes, Madrid, 2016, 393-440.

Concepción Lopezosa Aparicio, “Un singular edificio en el Prado Viejo de San Jerónimo: La torrecilla de música”, Anales de Historia del Arte, 5 (1995), 93-100. As found at: https://revistas.ucm.es/index.php/ANHA/article/view/ANHA9595110093A

Concepción Lopezosa Aparicio, “La imagen de la Ambición. El Real Gallinero en los Altos del Prado, Anales de Historia del Arte, Nº extra (2008), 213-228. As found at: https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2749271

Concepción Lopezosa Aparicio, “La residencia del duque de Lerma en el Prado de San Jerónimo. Traza de Gómez de Mora”, Madrid, 1 (1998), 457-486.

María Florencia Mendizábal, “¿Una ciudad para un rey? Reflexiones en torno a la construcción del espacio cortesano en Madrid (s. XIII-XVII)”, Estudios de Historia de España XIV, Universidad Católica Argentina, Buenos Aires, 2012, 161-184. As found at: http://erevistas.uca.edu.ar/index.php/EHE/article/view/60/63

Teresa Zapata Fernández de la Hoz, La corte de Felipe IV se viste de fiesta. La entrada de Mariana de Austria, 1649. Universidad de Valencia-Anejos de Imago, Valencia 2016.

| Title | A Stroll around El Prado in 17th-century Madrid: Scenery and Scenography of the Court |

| Author | Concepción Lopezosa Aparicio (Universidad Complutense de Madrid) |

| Web design | Kunsthistorisches Museum – Visual Media, Vienna |

| English Translation | Juan-José Martín-González (University of Málaga), Alexander McCargar (Yale University) |

| Image credits | Museum of the Castle Hochosterwitz (Launsdorf) - Khevenhüller Collection, Spanish National Library, Archive of the City of Madrid, Museum of History Madrid, Museo Nacional del Prado |

| Acknowledgments | Carmen Julia Guitiérrez, Fernando Pérez V, Juan Ruiz, Luis Robledo, Bartolomé Khevenhüller-Metsch, Alfredo Alvar Ezquerra. |