Splendorous Lisbon:

Art, Scenography and Pageantry in 1619

Pedro Flor

Universidade Aberta /

Instituto de História da Arte – NOVA/FCSH

At Weilburg Castle in Hessen, Germany, there is an extraordinary painting that represents the triumphal entry of King Philip III of Spain into the city of Lisbon in the year 1619.

Although the painting indicates on a cartouche the date of ‘1613’, it is now possible to ensure that this mistake was the result of an inaccurate restoration in the late 19th or early 20th century. The entire festival was performed during the king’s visit to Portugal from May to September 1619, accordingly to primary sources.

Anno Domini 1619. Under Spanish rule since 1581, Portugal received the monarch Philip III of Spain with full honours everywhere he went, from the western border in Elvas to Lisbon.

This painting shows us precisely the festive apparatus of the royal entrance to the city – a truly 'Joyeuse Entrée’.

Although it was a medieval tradition, the 'Joyeuse Entrée’ was widely used in early modern Europe. It consisted of a splendid and solemn ceremony organized on the occasion of the first visit of a high political or diplomatic individual. At that moment, the guest was supposed to demonstrate his commitment to local authorities and privileges of the inhabitants were guaranteed or confirmed.

Location of the painting: Schloss Weilburg. Bad Homburg, Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Hessen, inv. 1.1.160. Photo: Michael Leukel 2020.

This ‘Joyeuse Entrée’ followed a previously established route, where all the institutions responsible for the administration of the city, the city council, the confraternities or the guilds, played an essential role in the success of the whole event.

The painting shows us precisely the various moments and landmarks of the route: the arrival of the royal fleet to the river Tagus, then the parade at the Terreiro do Paço, the square to be seen in the picture, and finally, the way towards the Cathedral of Lisbon.

In sum, this painting is a rare pictorial testimony of an event of this nature, which is usually visually captured via prints or drawings.

What can we observe in detail on this painting? What information does it give us about the festival then organized to welcome the king? What are the differences between the painting and what actually occurred?

In this presentation, we will find answers to these and other questions...

As in a modern comic strip narrative, the painting simultaneously portrays the narrative of the events over several sequences.

The event starts during the previous days, when the king stayed on the outskirts of Lisbon, at the village of Belém. There, he patiently awaited the finishing of preparations of last-minute details of the great festival.

In fact, before leaving for Lisbon, Philip III’s retinue stayed in Belém, a pleasant village very close to the capital that had better logistical conditions for accommodation, namely the great monastery of the order of Saint Jerome, the mosteiro dos Jerónimos.

This building, the pantheon of Portuguese kings’ ancestors, was surrounded to the west by the Quinta da Praia, to the east by the village of Belém and, further north, by the Quinta da Calheta.

The Tower of Saint Vincent, the Torre de São Vicente, and the boats offshore greeted the royal family on their arrival with cannon salutes.

Further right, the painting depicts the events that occurred in 1619, from June 24th to 29th, towards the city of Lisbon.

38 years later, Philip III repeated his father's ritual, Philip II, who had entered the city in 1581 and had been received in a marvellous ‘Joyeuse Entrée’.

Before arriving at the city, the king's entourage sailed from Belém to Lisbon, passing through the neighbourhoods of Junqueira and Alcântara, founding the Saint Paul’s Church, the Irgeja de São Paulo, just in front of the Hills of Belver and Chagas, at the gates of Lisbon.

On 29th June, St. Peter’s day, the royal fleet was concentrated in the Tagus, in front of the most important square of the city: the Terreiro do Paço.

Through the heraldic representation and an attentive observation of all the flags and shields, it is possible to identify the origin of the galleys: England, Portugal, Malta, France, Catalonia and Spain. The painting is impressively exact concerning the details.

Windblown pennants and banners sweep the skies...

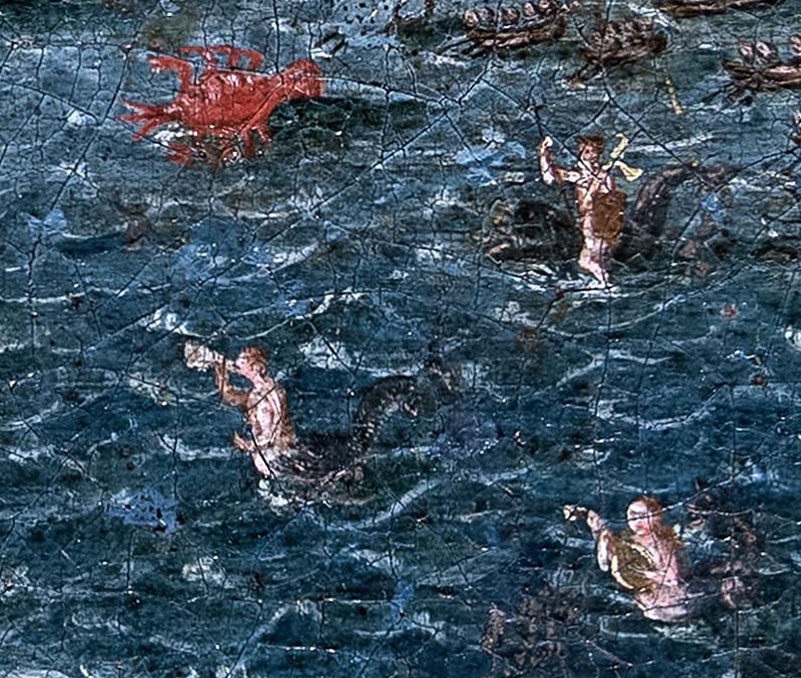

... showing several heraldic symbols and even religious figures of the extreme devotion to the Iberian Crown. In the Tagus, a parade welcomes the king’s retinue. It is composed of mermaids and tritons, dolphins and sea horses and other sea monsters, a true naumachia, staging a mass entertainment on water.

At 4 o'clock in the afternoon, amid the screams of the exuberant crowd and the artillery salutes, some of them coming from the Castle of Saint George, the Castelo de São Jorge, on top of the hill of the old medieval centre of Lisbon, it was still possible to hear the triumphant music coming from the boats that accompanied the appearance of the royal delegation at the pier of the Terreiro do Paço.

The painting reveals in detail the moment of the arrival of Philip III in Lisbon, in addition to the ceremonial handing over the keys of the city by the Senate of the City Council.

Covered with herbs and flowers, the pier, purposely built for the ceremony, appears in the foreground full of people who, in a euphoric climate, acclaimed the king. The imposing Arch of the Merchants of Lisbon serves as an ephemeral architecture that celebrates the event. More to the right, it is possible to perceive the presence of a stage where, according to the sources, the fight of the titans was represented, a ‘tableaux vivant’ inspired by antiquity and according to the taste of the time.

Along the river, a long portico of perfect round arches was painted, quoting from Serlio’s work “Tutte l'opere d'architettura”, including book VII, recently published in 1619 in Venice. The use of round arches in sequence with squares and balustrades seems to refer to the Bolognese architect. As in festivals before, the customs building was then fully depicted with mythological representations and several laudatory inscriptions about Philip III’s reign.

Now, let us see which route the king’s retinue took from the pier to the cathedral.

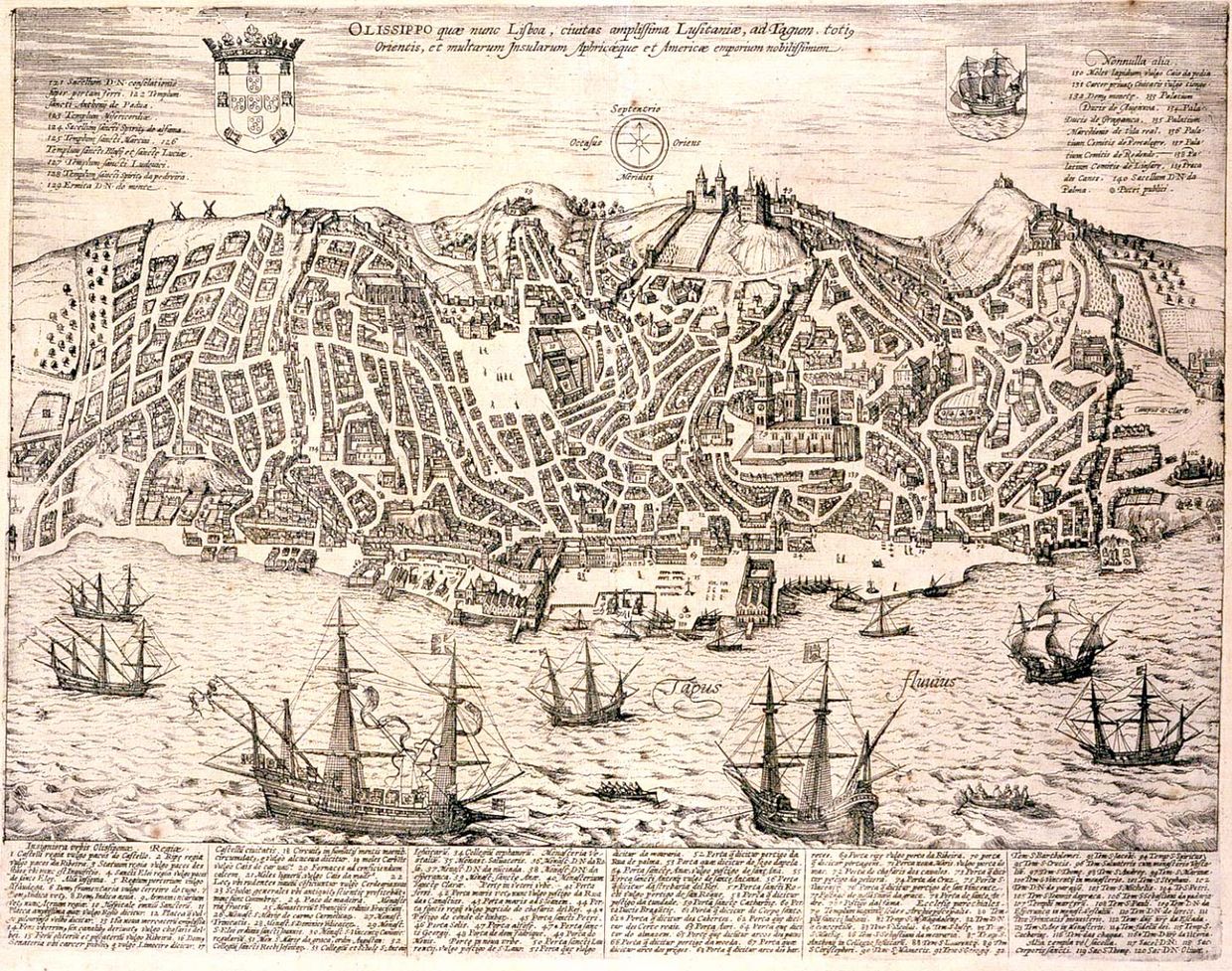

On the map, you can see the most important streets in Lisbon at the time, including the well-known and busy Rua Nova. The arches engraved by the Flemish artist Jan Schorquens, which lavishly illustrate the full account of João Baptista Lavanha, published in 1621–22,

both in Portuguese and in Spanish, where one can find a careful and detailed description of the whole ceremonies held in Portugal during Philip III’s visit. The arches are marked on the map with numbers. They correspond to the ones represented in our painting.

1 – Arch of the Merchants

2 – Arch of the Englishmen

3 – Arch of Waxsmiths

4 – Arch of the Italians

5 – Arch of the Holy Office of the Inquisition

6 – Arch of Germans

The king and his entourage went straight to the Cathedral, the most important religious building in the city. But first, they went through the Arch of the Merchants, then they passed the Arch of the Englishmen and started

to stroll the steep streets of Lisbon towards the Cathedral, appreciating the triumphal arches of classical taste and people performing in stages built to the effect, all full of color, movement and sound.

For the visual reconstruction of the ephemeral architecture of the festivals, fortunately, there are the prints by the Flemish artist Jan Schorquens, who has probably followed the events, to faithfully reproduce the entire ostentatious journey of the king.

When confronting the prints with the painting, we can clearly see the quality of the artist in reproducing all the events of that day.

The arch of the Englishmen was built at the place where one of the former gates of the medieval wall existed. In order to ensure a broader and more royal passage of the whole parade now being organized, Lisbon City Council ordered the demolition of the old gate of Ribeira.

The engraving by Schorquens and the painting of Weilburg give us a fairly precise idea of how carefully everything was prepared to greet the king.

After attending a solemn mass at the Cathedral, the entourage returned to the streets to continue the previously agreed parade.

The streets were still crowded, and the windows and balconies of the houses were decorated with bedspreads, painted cloths and other embroidery. There was no lack of colour, light or sound in all this splendorous route and the impact on all of the participants was enormous.

The entire route through the streets and arches came to an end at the Terreiro do Paço, the biggest square in Lisbon just in front of the Royal Palace at the riverside of the Tagus, and at the lavishly Arch of the Germans, the number 13 marked in the map.

The whole arch is an apotheosis of the Habsburg’s glory and greatness. The inscriptions in Latin are of encomiastic nature and stress the political preponderance of this magnificent dynasty. It reads like that:

“Great King and Lord, we do not offer Your Majesty the well-known fortitude of the Germans, nor its great power never subjected to foreign armies, if not as a sign of our constancy, here we depicted the portraits of the orders of the Holy Empire, which assist the Imperial dignity, alluding to the sentence of ‘Germania fides’ proverb, which celebrates their faith.”

To compose the whole panorama of Lisbon and its surroundings, the unknown artist of the Weilburg painting was relying on some visual sources to help him with the task of representing a city from a bird's-eye perspective.

To this end, he might have referred to the well-known plan of Lisbon, edited 1598 by Georg Braun in the fifth volume of the famous work “Civitates Orbis Terrarum”. This view must have been recorded by Joris Hoefnagel. As a curiosity, although the engraving was only known to the general public in 1598, it actually portrays the city as it was in about 1565, the time Hoefnagel travelled the Iberian Peninsula.

In addition to Hoefnagel’s bird’s eye view, the painter might have also been inspired by the engraving inserted in the aforementioned festival description by Lavanha, where one can see the arrival of Philip III of Spain to Lisbon. The engraving cartouche tells us that Schorquens drew from a painting by Domingos Vieira Serrão, a Portuguese painter in the service of the king. Some scholars even argue that the authorship of the Weilburg painting is precisely that of Domingos Vieira Serrão, not least because this painter is documented in Madrid in 1623, taking with him a painting with the entry of Philip III to Lisbon, in order to embellish the ‘Salon de los Espejos’, the mirror hall of the Alcázar palace in Madrid. Was Weilburg’s masterpiece a copy of that painting, which has disappeared from Madrid's royal collections?

So at last, after several postponements, a great pageantry of enormous splendor was organized to receive King Philip III of Spain and Portugal, who was then in 1619 visiting Lisbon for the first time, and where his son, Philip, would be sworn a legitimate heir.

Several countries, guilds, even the Holy Office of the Inquisition, and the Lisbon city council financed the construction of various ephemeral arches and all the expenses related to the ceremonies.

Fortunately, there is this extraordinary and rare painting, today in the Castle of Weilburg (in Hesse) in Germany, which shows us precisely the moment of the King’s entry and several sequences of the festivities then held following the tradition of ancient Roman triumphs... The centre of an oversea empire, which stretched “beyond Ceylon” to quote the Portuguese poet Camões, Lisbon has been transformed into a large theatrical space. This was one of the most expensive and impressive festivities of the early modern period on the Iberian Peninsula. The organization of the whole event was a true effort to emphasize the renewal of existing power relations between the Habsburgian King of Spain and the Portuguese people.

Acknowledgements

Ana Cristina Leite (GEO / Câmara Municipal de Lisboa)

Andreas Gehlert (Independent Scholar)

António Candeias (Laboratório HERCULES)

António Miranda (Câmara Municipal de Lisboa)

Carmen González-Román (Universidad de Málaga)

Fabian Wolf (Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Hessen)

Fernando Bouza Álvarez (Universidad Complutense de Madrid)

Isabel Sólis Alcudia (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia)

Joana Sousa Monteiro (EGEAC / Museu de Lisboa)

José Manuel Garcia (GEO / Câmara Municipal de Lisboa)

Miguel Metelo de Seixas (IEM-NOVA/FCSH)

Laura Fernández-González (University of Lincoln)

Milene Gil (Laboratório HERCULES)

Paulo Almeida Fernandes (EGEAC / Museu de Lisboa)

Renata Araújo (Universidade do Algarve)

Rudi Risatti (Theatermuseum – Kunsthistorisches Museum - Wien)

Sara Valadas (Laboratório HERCULES)

Susana Varela Flor (Instituto de História da Arte - NOVA/FCSH)

Victoria Soto Caba (Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia)

Whitney Jacobs (Laboratório HERCULES)

Selected Bibliography

GUÉNÉE, Bernard, LEHOUX, Françoise. Les Entrées royales françaises de 1328 à 1515. Sourcesd’HistoireMédiévale, Institut de Récherche et d’histoire des textes. Paris: Éditions du CNRS, 1968.

STRONG, Roy. Art and Power – Renaissance Festivals 1450-1650. Woodbridge: The Boydell Press, 1984.

ALVES, Ana Maria. As EntradasRégiasPortuguesas. Lisboa: Livros Horizonte, 1986.

MULRYNE, J.R., WATANABE-O’KELLY, Helen, SHEWRING, Margaret (eds.). Europa Triumphans: Court andCivic Festivals in Early Modern Europe. Vol. I Ashgate, 2010.

STARKEY, David. Royal River: Power, PageantryandtheThames. Greenwich: Scala Books / National Martime Museum, 2012.

GEHLERT, Andreas. “The Weilburg painting showing the Lisbon entry of 1619 in its historical and pictorial context”. En: Revista de História da Arte 11, IHA-NOVA/FCSH, (2014) 69-85.

CHECA CREMADES, Fernando, FERNÁNDEZ-GONZÁLEZ, Laura (ed.). Festival Culture in the World oftheSpanish Habsburgs. Routledge, 2015.

SOROMENHO, Miguel. “A Joyeuse Entrée de 1619”. En: JoyeuseEntrée – A Vista de Lisboa do Castelo de Weilburg. Lisboa: Museu Nacional de Arte Antiga, 2015, 29-70.

FLOR, Pedro (coord.). The Universal Square ofthewhole Orb. Lisboa: EGEAC/CML, 2019.

SOTO CABA, M.V y SOLIS ALCUDIA, I. “De la policromía efímera. Metodología e infomática para una recreación virtual del color. Los arcos lisboetas del desembarco de Felipe III (1619). En: El Rey Festivo. Palacios, jardines, maresyríoscomoescenarioscortesanos (siglos XVI-XIX). Ed. I. Rodriguez, Valencia, Universidad de Valencia, 2019, 67-80.

Sources

SARDINHA MIMOSO, J. Relación de la Real tragicomedia con que los padres de la Compañía de Iesus en su Colegio de S. Anton de Lisboa recibieron a la Magestad Católica de Felipe II de Portugal, y de su entrada en este Reino ... Impresso en Lisboa: por Iorge Rodriguez, 1620.

LAVANHA, João. Viagem da Catholica Real Magestade del Rey D. Filipe II. NS ao Reyno de Portugla e rellação do solene recebimento que nelle se lhe fez. Madrid: Thomas Iunti, 1622.

RODRIGUES LOBOS, F. La Jornada que la Magestad catholica del Rey Don Phelippe III de las Hespañas hizo a su Reyno de Portugal; y el triunfo, y pompa con que el recibio la insigne ciudad de Lisboa el año de 1619. Lisboa, Pedro Crasbeck, 1623.

OLIVEIRA, Eduardo Freire de. Elementos para a História do Município de Lisboa. Vol. II. Lisboa: Typographia Universal, 1885, 432-450.

GAN JIMENEZ, J. “La Jornada de Felipe III a Portugal (1619)”. Chronica Nova, 19 (1991), 407-431.

Image Credits

Weilburg painting © Staatliche Schlösser und Gärten Hessen / Photo: Michael Leukel 2020

Old Lisbon Maps © EGEAC / Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta

Jan Schorquens engravings from Lavanha’s Viagem © Biblioteca Digital Hispánica (bajo una licencia de Reconocimiento 4.0 Internacional de Creative Commons)

Music Credits

‘Tiento de Batalla’, Sebastián Aguilera de Heredia (1561-1627), Jordi Savall, Hespèrion XXI, Alia Vox (2009), Entremeses del Siglo de Oro.

This project has been realized with the support of:

Title : Splendorous Lisbon: Art, Scenography And Pageantry In 1619

Author: Pedro Flor – Universidade Aberta And Iha-nova - Fcsh

Web-design: Kunsthistorisches Museum – Visual Media, Vienna

Translation / Proof Reading: Pedro Flor, Daniela Franke, Nathanial Gardner

Voice: Pedro Flor