Baroque Lisbon:

Power and Representation

Susana Varela Flor

Universidade Nova de Lisboa

This is the story of an Infanta who was made Queen. This is a scene where one can see the public entrance of someone important. This is the depiction of a royal square on a busy day in the seventeenth century.

Created by the Dutch painter Dirck Stoop in 1662, this canvas portrays a moment from daily life in Lisbon, during the time in which the Portuguese crown were making the final preparations for the feasts in celebration of the wedding of the Infanta Catarina de Bragança, daughter of the Queen Regent Luísa de Gusmão, with the English monarch Charles II of the Stuart dynasty. This marriage strengthened the diplomatic ties between the Portuguese Court and its British counterpart. It also coincided with the troubled period in Portugal, which had been at war with Spain since 1640 and after the reinstatement of sovereignty: a period of Restoration ...

Authorship

Dirck Stoop (c. 1618–1686)

Dirck Willemsz van der Stoop, also known as Dirck Stoop, was born in Utrecht around 1618.

He lived with his family, including his father, Willem Jansz Stoop (d. 1646) a distinguished stained glass painter, and two brothers who were also painters, named Maerten and Jan. Dirck Stoop is also referred to in documents as a painter of horses, alluding to his main activity as an artist. Stoop´s name is also registered in 1638 at the Utrecht guild of painters. In 1647, after a sojourn in Italy, Stoop returned to Utrecht. The decade of the 1650s is the least documented period in his career. However, some authors theorise that Stoop worked in close partnership with other Dutch painters such as Jacques Muller (d. 1673), Willem Ormea (1611–1673) and Cornelis Willaerts (act. 1622–1666).

Dirck Stoop spent some time in Italy, as evidenced by the choice of classical motifs and architectural ruins such as arches, columns and entablatures in his works.

In the early 1640s, his sojourn in Italy was contemporary to the partnership established with the Dutch painter Jan Baptist Weenix (1621 – c. 1663). Historiography records a joint signature on a painting entitled “View of Tivoli”, unfortunately untraced. One can imagine what such a painting would look like when compared with others by Dirck Stoop that still exist.

The connection between Stoop and the kingdom of Portugal is still difficult to discern with precision. The arrival of Stoop in Portugal may be explained by contacts made in London, where he may have travelled during the late 1650s in search of new job opportunities.

If this journey to England were to be confirmed, Stoop would join the long list of Dutch painters who crossed the North Sea at this time, such as Peter Lely (1618–1680), Pieter Borselaer (c. 1664–1687) or Jacob Huysmans (c. 1633–1696), especially after the reinstatement of Charles II. The image depicting the King’s cavalcade through the city of London in 1661 seems to prove his stay in England in the early 60s. Once in London, Dirck Stoop may have met the Portuguese Ambassador, Francisco de Mello e Torres, an acquaintance of General at Sea (Admiral) Edward Montagu – Earl of Sandwich, later Ambassador Extraordinary to Charles II – who commissioned work from Stoop.

On 23rd June 1661, Francisco de Mello e Torres (c. 1610-1667), signed in London the Whitehall Treaty on behalf of the Portuguese Crown. The signing of this peace and trade alliance proved to be an important turning point in the political role that Portugal would play in Europe after gaining its sovereignty from Spain.

Accordingly, the marriage between Catherine of Braganza and Charles II of England was considered to be as a great diplomatic victory for the House of Braganza in the post-Restoration period. In September 1661, Dirck Stoop was in Lisbon, accompanying the English Ambassador Extraordinary Edward Montagu, who had come to Portugal. Stoop’s mission was the iconographic recording of events related to the marriage ceremonies of Catherine of Braganza to Charles II and its festivities, as shown here...

Stoop painted the canvas, subject of this presentation, which he signed and dated as “London 1662”. It may have been a commission by the Portuguese Ambassador Francisco de Mello e Torres extolling his rise to the Marquisade of Sande.

Dirck Stoop’s works and their dissemination provided an ‘opportunity to promote the image of Lisbon in Europe’, as well as establishing the basis for the iconographic representation of Lisbon. This canvas seems to be a good example of such promotion.

“Terreiro do Paço”

A Town Square as a Stage

Since the 16th century, the area facing the Royal Palace of Ribeira became the main centre of city life, a true stage for intense mercantile activity and also for representation of the principal political and diplomatic events of the kingdom.

The beginning of this tradition goes back at least to the reign of King Manuel I and it was perpetuated throughout in the following centuries. The importance of this square resided not only in the imposing presence of the royal palace, but also in several other buildings that surrounded it, including the ‘Casa da India’ (the heart of mercantile activity within the vast Portuguese Atlantic and Asian domains), and also the Customs, which received and managed all the entry and exit of goods to the kingdom.

The map drawn by the architect João Nunes Tinoco (c. 1650) effectively shows us this wide space, facing the river. You can also see, on the right, the medieval district of narrow and winding streets and, on the left, the orthogonal Bairro Alto with well-defined spaces and blocks.

Most of the representations of this great square, called Terreiro do Paço, show the versatility of the enormous enclosed space, between the fort of St. John, the palace and the old doors of the medieval wall of Lisbon.

This area easily allowed the assembly and disassembly of ephemeral architectures such as archways and triumphal arches, used in the festivities organized around an event.

This is clearly visible in paintings of iconographic relevance which we can now observe. This is the depiction of the king's oath ceremony, after the proclamation of independence in 1640, following 60 years of Spanish rule. When observe with more scrutiny, we see that it was the east-facing wall of the Royal Palace that was used for the construction of the stage on which the oath was to take place. The intense red and gold colours of the fabrics used lend to the scene an enormous sense of the magnificence of the ceremony. Furthermore, the procession full of pomp and circumstance develops further to the right, where we see in detail the king on horseback, under a white pallium, surrounded by several elements of the highest clergy and nobility.

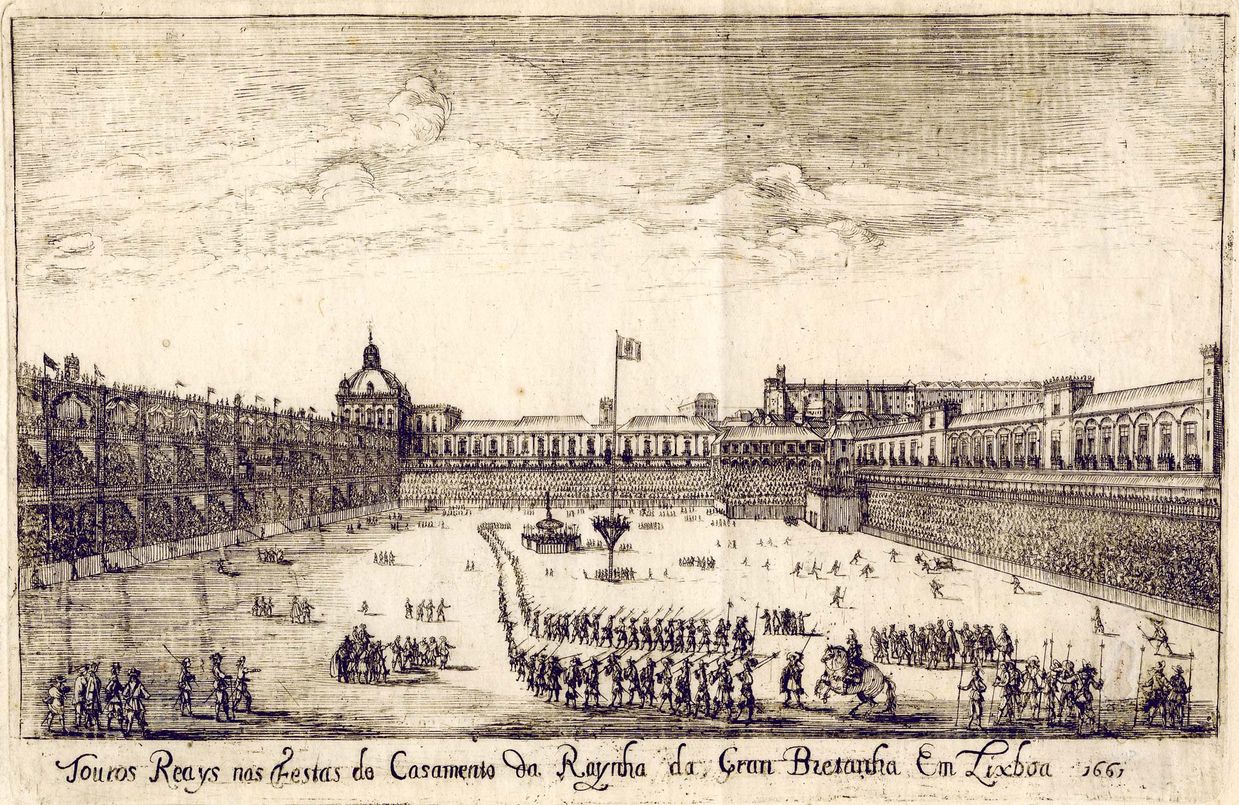

Another example of Terreiro do Paço's enormous versatility is the following engraving:

The square is heavely decorated and fully crowded with people. One can see examples of ephemeral architecture, covered with classical quotations and draped in cloths and fine fabrics, as was the style in vogue in the arts at the time.

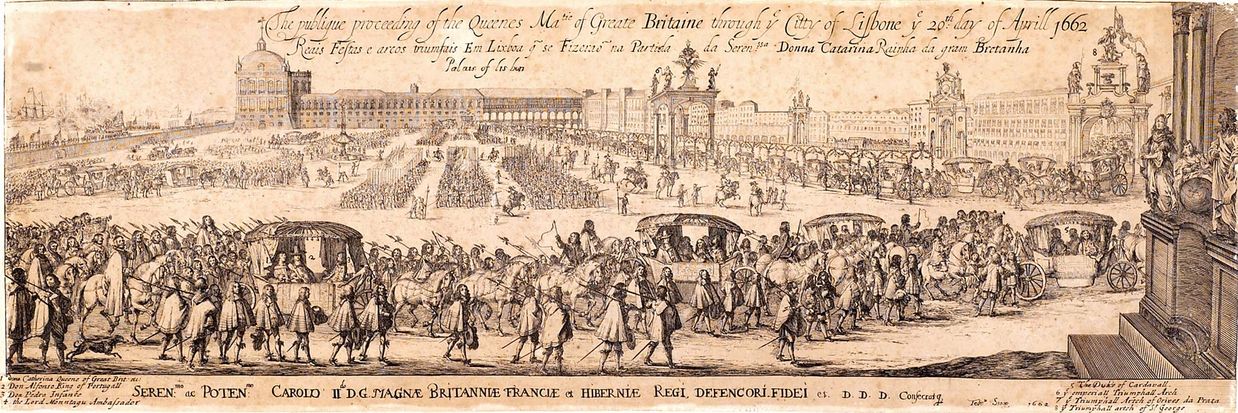

This engraving shows us the festivities that took place on the circumstance of the celebration of Catherine of Bragança's marriage to Charles II. The triumphal arches both in the middle of the square and next to the doors of the ancient walls of Lisbon, not to mention the parade of richly decorated carriages accompanied by a retinue of guards who lend it majesty and nobility underline, once again, the usefulness of the enormous space and the scenic potential contained within it.

Even in times after Stoop’s painting, the use of the great royal square was maintained as a privileged space for celebration, as can be seen in this other stunning painting. It shows the arrival of the Apostolic Nuncio to the Terreiro do Paço in 1693, Monsignor Giorgio Cornaro, moments before the first audience with the Portuguese king, Pedro II. It is worth noting, for example, the parade of carriages on the right side of the painting, the enormous ephemeral arcade that was built next to the buildings to receive the various institutional and local authorities and the exhibition of covers and fabrics on the windows of the houses facing the square.

All this magnificent atmosphere was no stranger to the people of Lisbon who had become accustomed to going to Terreiro do Paço for such events of pomp and pageantry.

Let us take another look at Dirck Stoop’s painting again. Taking advantage of the massive Royal Palace of Ribeira, our painter frames the Terreiro and displays various and isolated stories that are justified in the historical context of the marriage agreed between the royal houses of Portugal and England in the year 1662.

Architecture

The iconographic potential of our painting and the painter's very accurate vision allow us to enjoy its narrative richness that helps us to explore its content. Movement, sounds, daily-life and scenography seem to invite us to enter the painting and participate in it as well.

Let's start with the architecture represented in the painting which occupies a significant part of it in visual terms. Although the scene we are looking at has never actually happened, the painter tried to simulate it, capturing a sort of a photographic snapshot, in today´s terms. However, in order to provide authenticity to the painting, Dirck Stoop carefully drew the huge royal palace with its imposing tower; a horizontal gallery, which made the connection between that tower and the vacant hall of the so-called German guard, and finally, closing the representation, the Ladies´ Gallery. Other identifiable buildings can be seen in the distance.

Main narratives

One of the most interesting strategies Stoop applied to this painting was to condense several narratives into the one scene, none of which occurred simultaneously, but individually.

However, when we look at the scene in general, we find that everything seems to work as a whole. Each of the small sets of characters has a function and they tell us a short story that relates to the overall theme of the painting: the marriage of Catarina de Bragança.

Daily life

The richness of iconographic content of the whole scene is such that one can still identify other small episodes within the stage that is to say the great square of Terreiro do Paço, even though they have no direct link to the main theme of the painting.

Portraits

Along with the portraits of Catarina de Bragança, the Queen Luísa de Gusmão and the nun in the centre of the painting, it is noticeable by the prominence given to the three characters in the foreground that these are another three portraits.

They are clearly prestigious and important people in the court of time. Unfortunately, we have not yet been able to identify them, but the detail in their likenesses and the way they present themselves in front of the observer leave us with no room for doubt.

Selected Bibliography

Fernando Castelo Branco, Lisboa Seiscentista - Livros Horizonte, Lisboa, 1990.

Carlos Caetano, A Ribeira de Lisboa na Época da Expansão Portuguesa (Séculos XV a XVIII) - Pandora, Lisboa, 2004.

Júlio de Castilho, A Ribeira de Lisboa. Descripção Histórica da Margem do Tejo desde a Madre-de-Deus até Santos-o-Velho - Imprensa Nacional, Lisboa, 1893.

Miguel Figueira de Faria (coord.), Do Terreiro do Paço à Praça do Comércio – Imprensa Nacional Casa da Moeda / UAL, Lisboa, 2012.

Susana Varela Flor, Aurum Reginae orQueen-Gold: a iconografia de D. Catarina de Bragança entre Portugal e Inglaterra de Seiscentos - Fundação da Casa de Bragança, Lisboa, 2012.

Susana Varela Flor and Pedro Flor, Retratos do Paço Ducal de Vila Viçosa, col. Muitas Cousas, n.º 6 – Fundação da Casa de Bragança, Lisboa, 2018.

Jorge Penim Freitas, Guerra da Restauração – Blog de história militar dedicado à Guerra da Restauração ou da Aclamação. Available in:

https://guerradarestauracao.wordpress.com [accessed 04-07-2020]

Bruno A. Martinho, O Paço da Ribeira nas Vésperas do Terramoto - Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisboa [texto policopiado], 2009.

Rafael Moreira, “O Torreão do Paço da Ribeira” in: Mundo da Arte, 14 (1983) - Imprensa de Coimbra, Coimbra, 43-48.

Nuno Senos, O Paço da Ribeira (1501-1581) - Ed. Notícias, Lisboa, 2002.

Ernesto Soares, Dicionário de Iconografia Portuguesa, Vol. V, II suplemento, Lisboa, IAC, 1960, p. 313.

P.T.A, Swillens, “De Utrechtche Schilders Dirck en Marteen Stoop” in: OudHolland – Journal for ArtoftheLow Countries, Brill, 1º, 1934, pp. 116-135.

Provenance of images

1) Lisboa, Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta (inv. MC.PIN 261)

2) Utrecht, Centraal Museum (inv. 2298) - ©CC-PD-Mark

3) Image available in: https://www.christies.com/lotfinder/Lot/dirck-stoop-utrecht-c-1618-c-1686-5101494-details.aspx ©Christies

4) London, British Museum, The Coronation procession of Charles II in four rows (numbered 17-20); beginning with "Sergants at Armes" and ending with "Captain of the Guard"; being the last of four plates of this event taken from John Ogilby's 'The Entertainment of ... Charles II', 1662 Etching, inv. 163613001, ©The Trustees of the British Museum, (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

5) Lisboa, Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta (inv. MC.GRA 503)

6) Lisboa, Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta (inv. MC.DES 1084)

7) Lisboa, Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta (inv. MC.PIN 262)

8) Vila Viçosa, Paço Ducal de Vila Viçosa (inv. 4815)

9) Lisboa, Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta (inv. MC.GRA 1074)

10) Lisboa, Museu Nacional dos Coches – image available in: artsandculture.google.com/asset/JQHiTENYrWsC4A ©CC-PD-Mark

11) Lisboa, Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta (inv. MC.GRA 1885)

Credits

Title: Baroque Lisbon: Power and Performance

Author: Susana Varela Flor (Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Instituto de História da Arte – Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas).

Web Design: Kunsthistorisches Museum – Visual Media, Vienna

English Translation / Proof Reading: Susana Varela Flor / Erin Coghill

Funding: The research undertaken for this digitorial has been funded by the Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia-FCT, as part of its Norma Transitória programme [DL 57/2016/CP1453/CT0032].

This Digitorial has been realized through a funding of Museu de Lisboa – Palácio Pimenta / EGEAC