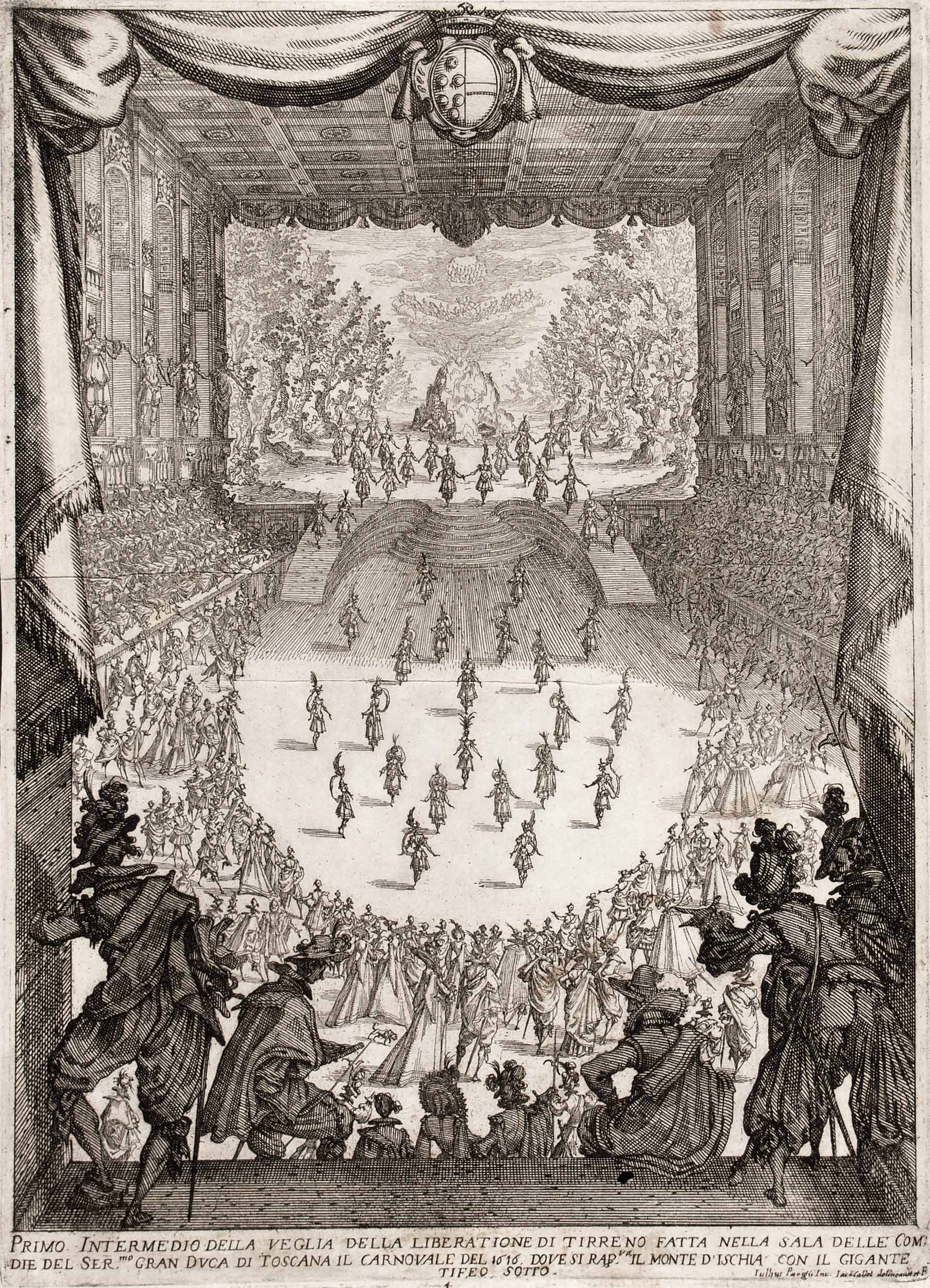

The intermedi of La Pellegrina

(1589)

Siro Ferrone, Sara Mamone, Anna Maria Testaverde

Florence, 1589. On the occasion of the reigning Grand Duke Ferdinando I de’ Medici’s marriage…

… to Christine of Lorraine. It’s one of the fundamental episodes in the theatre of the Ancient regime’s history. The performance was increasingly becoming an instrument to display the power and technological capacity of the lord and his court.

Florence, the capital of the Grand Duchy, anticipated this synthesis of art and power. This period must be considered, due to the inventions and the technological advancements, and its resonance in all the European courts, as the acme of this experimentation.

Among the great novelties was the development of a system that saw the very idea of theatre resurrected after centuries: all previous experiments had taken place in temporary locations. Another great novelty: in the Palazzo degli Uffizi, a new space was added to the Grand Ducal Theatre. This was destined for an increasingly popular phenomenon: the Commedia dell'Arte.

The show, in a specially built indoor space, is the culmination of very complex festivities and is perhaps the most important period in the entire history of the Court Theatre.

This new type of show, developed in the Uffizi theatre, went on to be so successful that it would become a true model for the great Baroque theatre.

Fixing the over three centuries old hierarchy of spectators and replicating the ‘Great theatre of the world’: that of society.

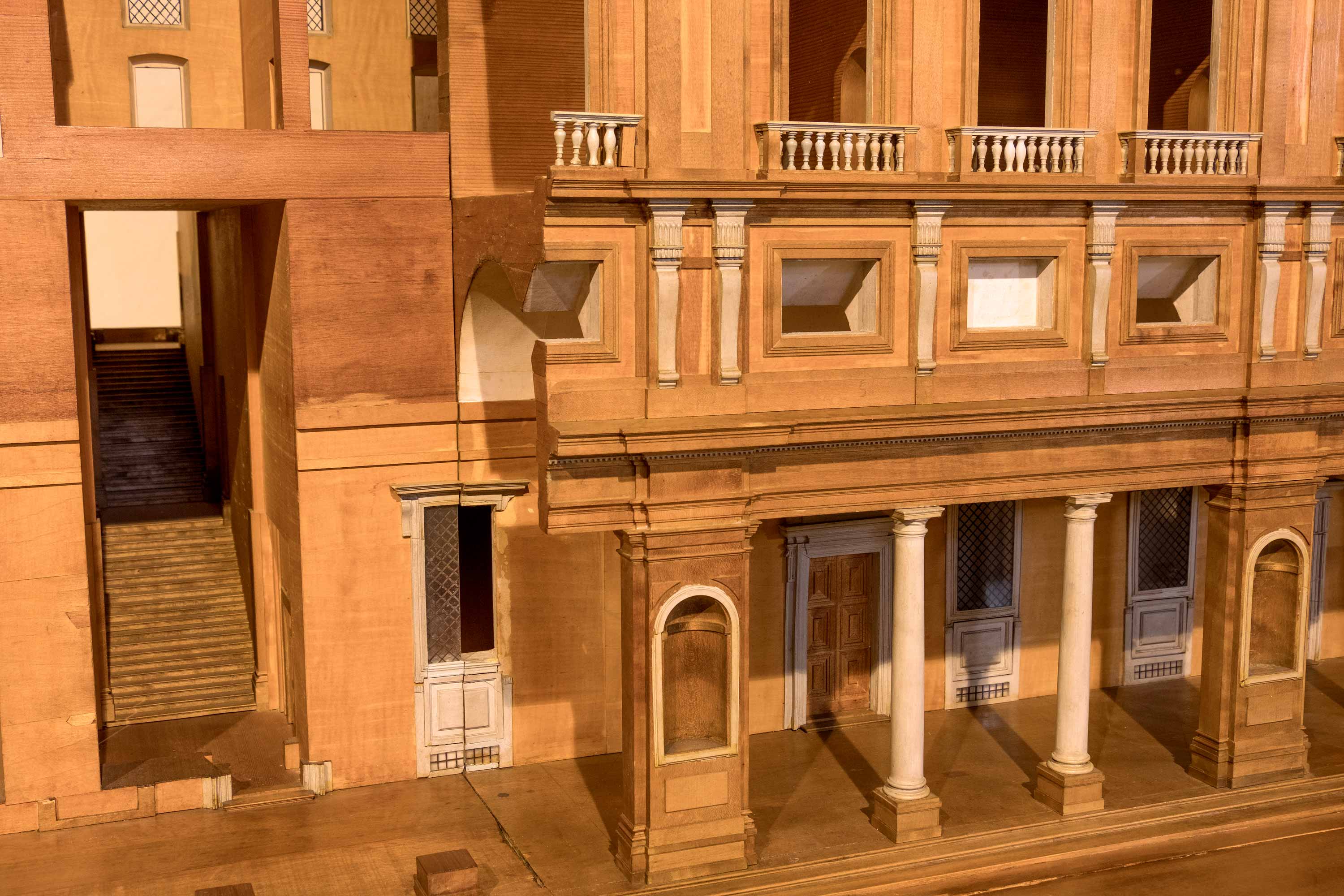

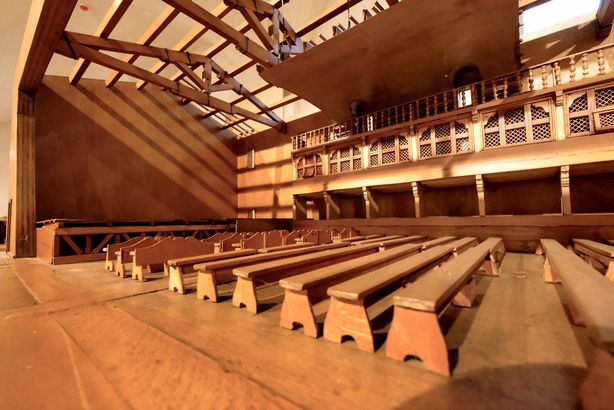

On the first floor of the building a large hall was built, destined to host the great shows of the dynasty. The guests had access, through the entrance under the portico, to the staircase leading into the hall.

The theatre was of considerable size, measuring about 54m long, 20m wide and 14m high.

About two thirds into this room, the Prince’s stage is placed axially to the scene.

It was the Prince’s position that would determine the focus of the perspective scene -position, further highlighting his role as sovereign.

The Uffizi theatre could comfortably accommodate all of the Grand Duke’s guests. It was to become, therefore, the model on which all of the theatres of the European courts were inspired. It remained in use until the 40s of the following century, before being replaced by newer theatres.

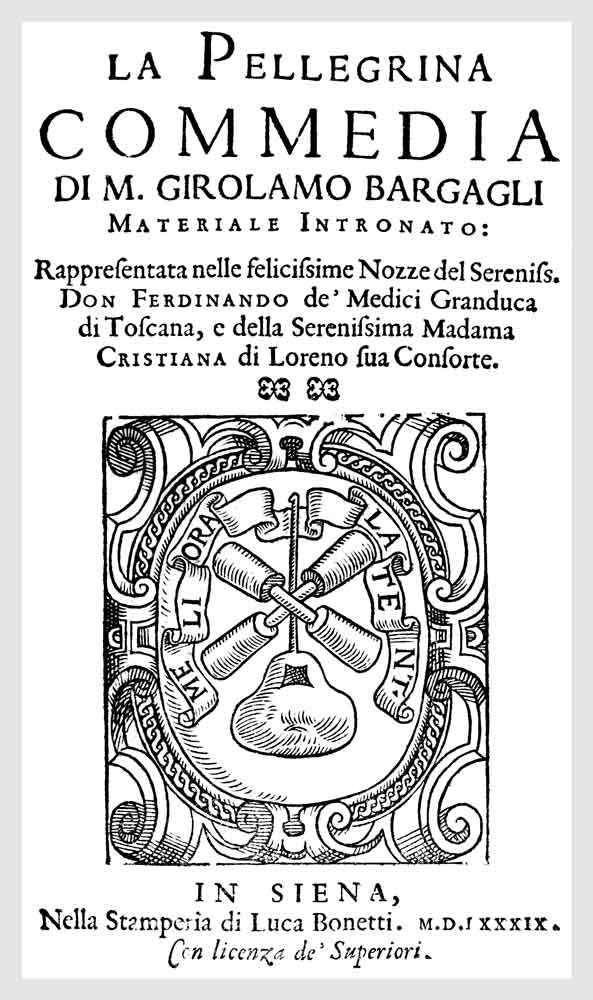

As historical sources testify the comedy represented was La Pellegrina by the Sienese academic Girolamo Bargagli. This part of the show was of no interest, as it corresponded to an old-fashioned genre of performance, if compared to the maturation of the audience. The spectators were indeed more and more experienced and demanding. The entire episode is described in detail by the official reporter Bastiano de’ Rossi and by Giuseppe Pavoni.

The disinterest for the comedy La Pellegrina is already evident from the small effort made for the comedy, compared to the expensive and all-encompassing so-called "Intermedi". Compared to the five acts of the Comedy the intermedi contained six, opening and closing the entire show. All the forces of the Grand Duchy were to be utilised by the intermedi.

The Staff

Emilio de’ Cavalieri was in charge of the coordination, Giovanni de’ Bardi was the creator of the themes (almost a modern dramatist) while the responsibility for the arrangement was entrusted to the court architect Bernardo Buontalenti. A large number of artists and craftsmen were employed by all three men.

The whole staff

Provider of the comedy

Girolamo Seriacopi

Scholars

Girolamo Bargagli

Giovanni de’ Bardi

Ottavio Rinuccini

Giovanni Battista Strozzi

Laura Lucchesini

Composers

Antonio Archilei

Cristofano Malvezzi

Luca Marenzio

Giulio Caccini

Giovanni Bardi

Jacopo Peri

Emilio de’ Cavalieri

Antonio Naldi detto il Bardella

Buontalenti had just set up the Dogana district right behind the Uffizi Palace, equipping it with a for profit theatre, called the Teatro della Dogana (or also Teatro di Baldracca), where the actors of Comici dell’Arte used to perform.

And it was precisely these comedians who replaced the acts of the Comedy when it was eliminated from the revivals of the intermedi, which were a resounding success. It was to be Isabella Andreini and Vittoria Piissimi, the two great ‘divas’ of the professional theatre, who would be ‘taken’ from the adjoining Teatro della Dogana to charm the spectators with their talents from one Intermedio to another.

Teatro della Dogana or di Baldracca

Professional actors had a relative autonomy with respect to the courts which, however, given the growing interest in the phenomenon, hurried to build or adapt stanzoni to the public performance, i.e. open to anyone who could pay the price of the ticket. In Florence the del soldo theatre had been active since the second half of the sixteenth century in the premises of the river customs, an old warehouse at the back of the Uffizi, adapted for that use by Bernardo Buontalenti on the occasion of the restoration of the entire area of the port on the river Arno. The most important art companies played on its stage, including that of the Gelosi who also performed in the grand-theatre of the Uffizi on the occasion of the replica of the intermedi of La pellegrina in 1589. The seats were clearly divided into two sections: the benches and seats were occupied by the audience of paying spectators who entered through a special entrance on the customs square.

On the other hand, the prince, the special guests and the nobility stood in special boxes hidden by gratings, with direct access from the rooms of the main building. The actors stood on the raised stage in front of the stalls and were often housed in the upper rooms where they could stay during the performances, thus saving on board and lodging, as there were many expenses: in addition to the actors’ pay, the budget included travel expenses, costumes and props (the so-called robbe). The earnings were sometimes burdened by the cost of renting the hall and taxed by a compulsory contribution to the San Giovanni di Dio Hospital, introduced under the name of jus represaentandi, by Philip II of Spain. This obligation, was a sort of ‘penance’ for any accusations of obscenity that accompanied the comedians and their profession. The small theatre, active for about a century, was closed in the second half of the seventeenth century.

To get further details …

… on the actors of Commedia dell’Arte and the expansion of the phenomenon in Europe, see Siro Ferrone, Attori, mercanti, corsari. La Commedia dell’Arte in Europa tra Cinque e Seicento, Torino, Einaudi, 1993.

Isabella Andreini and the actors

Isabella Andreini Canali (Padua ca. 1562 - Lyon 1604), wife of the actor Francesco Andreini (who played the role of captain) and mother of the actor and playwright Giovan Battista “innamorato” – also known as Lelio, was the first actress of the Gelosi company, together with Vittoria Piissimi (Ferrara, ? – place unknown, after 1595), in the role of “innamorata”. At this chronological height they were both famous and, even if the following fame will surround Isabella with the aura of an absolute diva, they had the same importance, in fact Vittoria was perhaps more in demand, since she almost passed as a soloist in various companies. During the celebrations for the Grand Duke's wedding, the Gelosi troupe performed in the theatre for a fee at the customs:

the success of the two actresses is such that they were called directly by the Grand Duke to cheer up the chosen audience of the Uffizi theatre on the occasion of the rehearsals of the play La Pellegrina. The staging of the play was unsuccessful, completely obscured by the triumph of the Intermedi and Ferdinando I wanted, in replicating them, to eliminate the acts of the play and give space to the triumphants of professional theatre, promoting them from the Teatro della Dogana to the stage of the Uffizi, where they played their battle horses separately. The chronicles of time also accurately report the event.

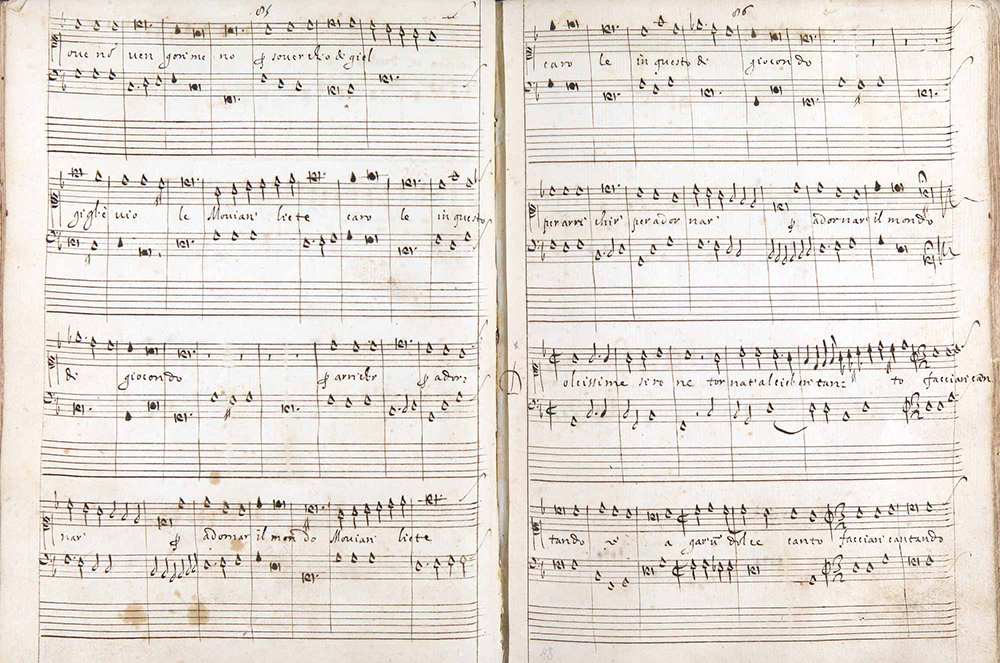

The Six Intermedi

Let us now come to an illustrative reconstruction of the six intermedi of the comedy La Pellegrina. Its themes are very sophisticated, but we must remember both the circumstances of the event and the formation of the public, all rigorously selected and involved in the ‘high’ culture of the time.

First intermedio

L’armonia delle sfere // The harmony of the spheres

The first intermedio is based on the neo-platonic theories about the birth of the Harmony of the Universe and its descent to earth to be part of the newlyweds and the audience.

The interpreters of the first intermedio

Authors of the texts

Giovanni de’ Bardi

Ottavio Rinuccini

Composers

Antonio Archilei

Cristofano Malvezzi

Interpreters

Vittoria Archilei

Onofrio Gualfreducci

Ludovico Belevanti

Pietro Masselli

Mario Lucchesini

Alberigho

Giovanni del Minugiao

Pierino castrato

Bono signor Mongallo

Cristofano

Cesarone basso

Antonio Archilei

Peri Jacopo, known as lo Zazzerino

Naldi Antnio detto il Bardella

Giovanni Lapi

Baccio Polibotria

Niccolò Castrato

Giovan Battista del Violino

Raffaello Gucci

Giulio Romano

Seriacopi Giovanbattista

Duritio

Zanobi Ciliani

Giovanni del Franciosino

Second intermedio

La contesa tra le Muse e le Pieridi //

The dispute between the Muses and the Pierid

After the first act of La Pellegrina, the set of the comedy is covered from sight, by that of the intermedio.

Third intermedio

Combattimento pitico di Apollo // Apollo Pythios’ fight

The intermedio recalls the games of Delphi in honour of Apollo, slayer of the dragon that infested the island. The fight will be represented with a pantomime (dramatic dancing action).

The interpreters of the third intermedio

Author of the text

Ottavio Rinuccini

Composer

Luca Marenzio

Performers

Alessandro del Franciosino

Lucia

Tommaso

Polibotria Baccio

Duritio

Placito

Jacopo Peri, known as Zazzerino

Alberigho

Giovanni Lapi

Fourth intermedio

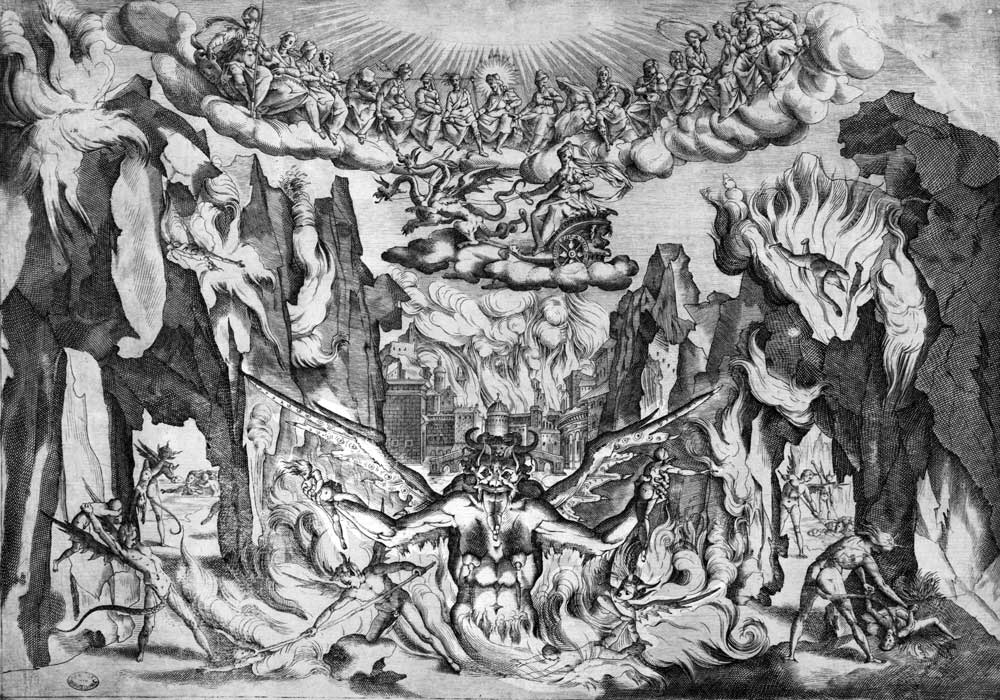

La regione dei demoni – Inferno //

The supposed Land of the demons – Hell

The fourth intermedio is based on the contrast between the disharmony of the world and the auspicious omen of the harmonious reunion under the wise government of the bride and groom, Ferdinando and Christine.

The costume sketches are lost, but were probably lent in their entirety at the request of some foreign court. The similarity of many of the costumes designed for the masques by Inigo Jones may suggest that they were taken the English court’s way. Moreover, it should be pointed out that all the European courts were oriented towards the Medici shows of 1589: the Florentine one becoming a model that saw a large distribution across Europe.

The interpreters of the fourth intermedio

Author of the text

Giovanni Battista Strozzi

Composers

Giulio Caccini

Cristofano Malvezzi

Giovanni Bardi

European distribution of the Florentine theatre tradition

The year 1589 is certainly one of the most important in the history of court entertainment in Europe. The complexity of the intermedi and the competence reached by the entire productive apparatus became a model for the courts of Europe. The Grand Duchy skillfully exploited this supremacy to make ever closer ties with the reigning families of the continent. Diplomatic relations were strongly influenced by the desire to emulate the great powers and Florence found itself at the centre of a dense network of exchanges. This period perhaps marked the culmination of experimentalism and also made way for the distribution of the skills of Tuscan engineering. The architects and grand-ducal workers became the most sought-after on the international circuit. At this turn of the century and then in the first half of the seventeenth century Europe would have the mark of Florentine spectacularism.

In France Henry IV enlisted Tommaso Francini to give Paris the appearance of a true capital. In Spain Cosimo Lotti and Baccio del Bianco would be the authors of the palace of delights of the Buen Retiro. The England of the Stuarts would find in Costantino de’ Servi his mentor, while Inigo Jones, after practicing in the Florentine atelier of Giulio and Alfonso Parigi, gave the English court the splendor of the Masques. The empire saw in Alessandro Pieroni and again in Baccio the creators of its updated theatrical life, followed in the mid-seventeenth century by Giovanni and Lodovico Ottavio Burnacini, who kept on developing the Buontalenti technology in Venice and then exported it to Vienna. Florence was to be a mandatory leg on the training tour, as evidenced by Joseph Furttenbach’s trip, which transferred the magnificence of the Medici’s stagecraft to the Hapsburg area.

Fifth intermedio

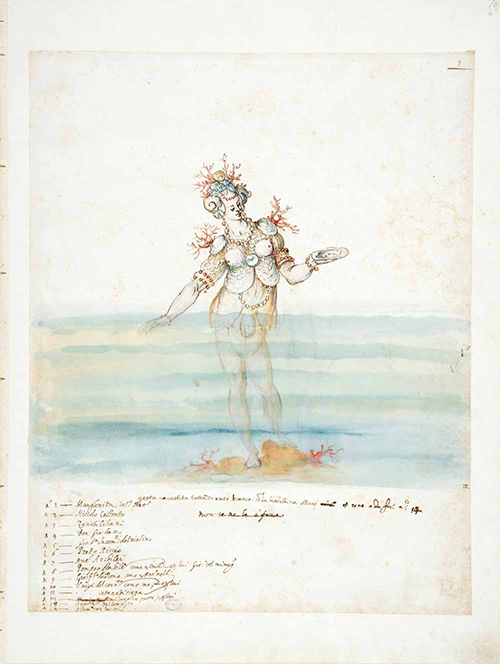

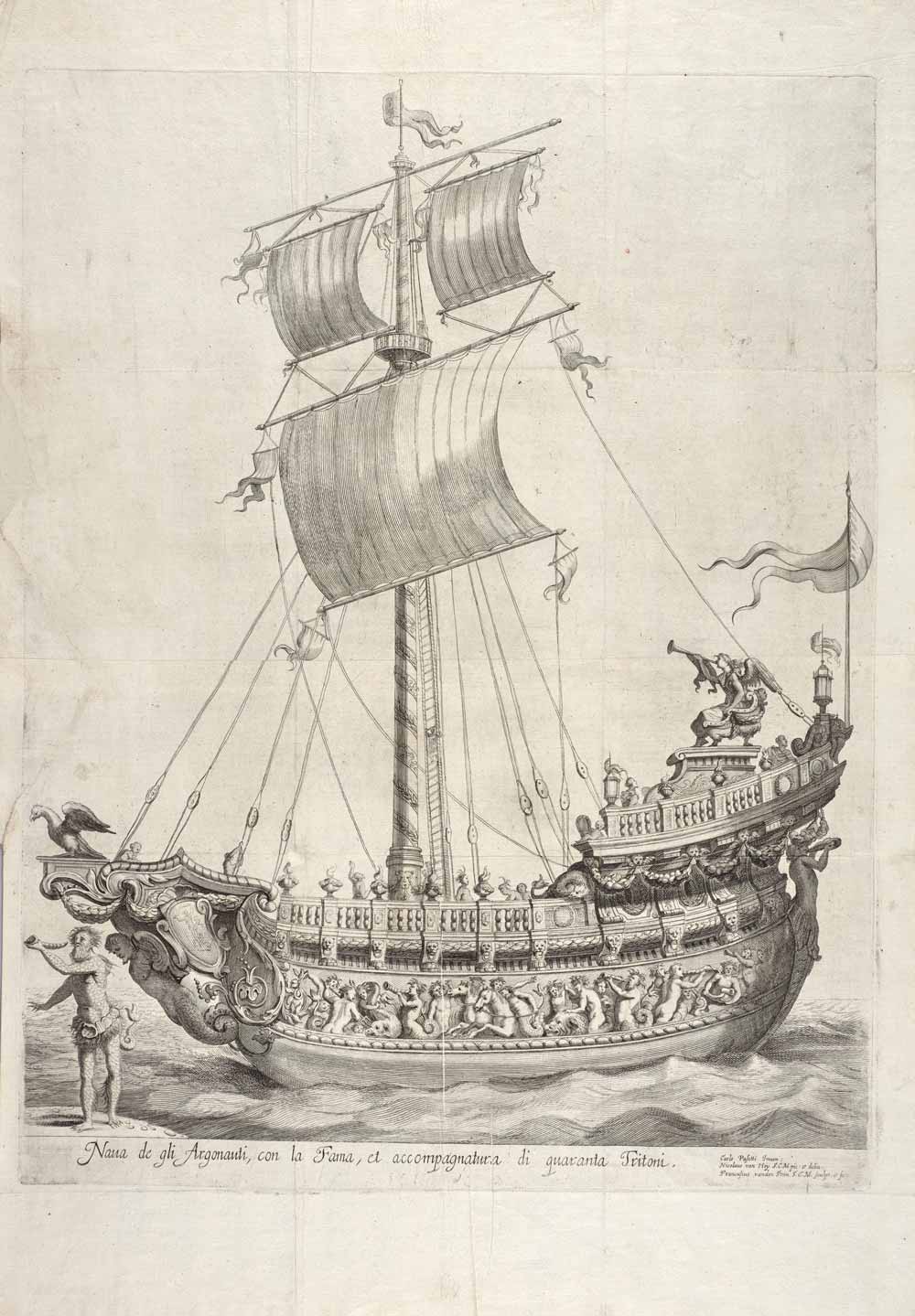

Anfitrite e la nave di Arione // Amphitrite and Arion’s vessel

The fifth intermedio reproduces a maritime scene, according to the already consolidated alternation of the stagecraft attractions that included the representation of the four elements: air, water, earth, fire. The chosen theme is that of the saving value of the music represented by the myth of Arion, the zither player saved by dolphins.

The main characters of the fifth intermedio

Authors of the texts

Ottavio Rinuccini

Giovanni Bardi

Ottavio Rinuccini

Composers

Cristofano Malvezzi

Jacopo Peri

Interpreters

Lucia Caccini

Vittoria Archilei

Jacopo Peri

Paolino del Franciosino

Oratio del Franciosino

Giovan Battista del Franciosino

Piero Maselli

Mario Luchini

Raffaello Gucci

Fra’ Lazzaro

Zanobi Ciliani

Antonio Naldi

Cesare basso

Ludovico Belevanti

Giovanni Lapi

Tonino del Franciosino

Piero castrato detto Acquatrice

Sixth intermedio

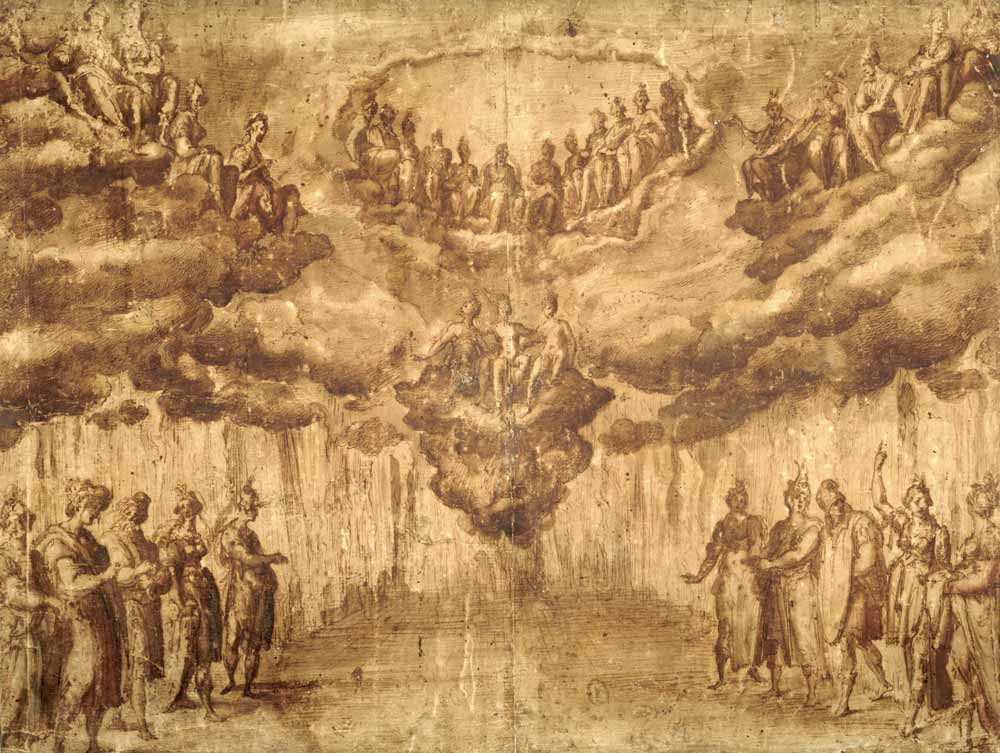

Gli dei inviano ai mortali l’Armonia e il Ritmo //

The gods send the mortals Harmony and Rhythm

The sixth and final intermedio takes up the theme of the first: a neo-platonic allegory on the consolatory meaning of music in the order of the Cosmos. Touched by the anxieties of men, the gods and Jupiter in particular, send Harmony and Rhythm to earth

The interpreters of the sixth intermedio

Authors of the texts

Ottavio Rinuccini

Laura Lucchesini

Composers

Cristofano Malvezzi

Emilio de’ Cavalieri

Interpreters

Vittoria Archilei

Archilei Antonio

Lucia Caccini

Jacopo Peri known as Zazzerino

Naldi Antonio known as Bardella

Giovanni Lapi

Polibotria Baccio

Niccolò castrato

Ceserone

Giovan Battista del Violino

Raffaello Gucci

Romano Giulio

A contralto from Rome

Seriacopi Giovan Battista

Duritio

Zanobi Ciliani

Mario Luchini

Alberigho

Giovanni del Minugiaio

Luca Marenzio

Don Giovanni basso

Ludovico Belevanti

Onofrio Gualfreducci

Pietro Masselli

Pierino castrato

Mongallo

Porcelli Bono

Cristofano

Giovanni del Franciosino

Giovan Battista del Franciosino

Paolino del Franciosino

Antonfrancesco del Bottigliere

Orazio del Franciosino

Prete Riccio

Tonino di maestro Lena

Paolino Stiattesi

Pietro Malespini

Orazio Benevenuti

Il Biondino del Franciosino

Il Feduccio

Roberto Ronai

Benedetto Guardi

Pompeo Stabiule

Fra’ Lazzaro

Domenico Rossino

Placito

Alessandro del Franciosino

Frate dell’Annunziata

Stabile

Cetera di Siena

"When this ended, much earlier, than the listeners would have wished, Heaven closed up. Those who were on earth, dancing, and singing, went away, by several routes, and left that very shining scene, and with their departure, they brought an end to the noble representation".

Historical sources

Bastiano de’ Rossi, Descrizione dell’apparato e degli intermedi fatti per la commedia rappresentata in Firenze nelle nozze del Serenissimo Don Ferdinando Medici, e Madama Cristina di Loreno Gran Duchi di Toscana, in Firenze, Padovani 1589.

Intermedii et concerti, fatti per la Commedia rappresentata in Firenze nelle nozze del serenissimo Don Ferdinando Medici, e Madama Christiana di Loreno, gran duchi di Toscana, In Venetia, Appresso Iacomo Vincenti, 1591.

[Giuseppe Pavoni ], Diario descritto da Giuseppe Pavoni delle feste celebrate nelle solennissime nozze delli serenissimi sposi, il sig. don Ferdinando Medici, & la sig. donna Christina di Loreno gran duchi di Toscana : nel quale con brevità si esplica il torneo, la battaglia navale, la comedia con gli intermedii , et altre feste occorse di giorno in giorno per tutto il dì 15. di maggio, MDLXXXIX ; nella Stamperia di Giovanni Rossi, Firenze 1589.

Bibliography

Nicola Badolato, “Rileggere i ‘costumi teatrali’ di Aby Warburg: lo sguardo del musicologo”, in: I molti rinascimenti di Aby Warburg , Schifanoia, 42-43 (2012), 189-199.

Franco Berti, “I bozzetti per i costumi”, in: La scena del Principe, Electa-CentroDi-Alinari-Scala, Milano-Firenze 1980, 361-363 e relative schede.

Franco Berti, “Studi su alcuni aspetti del diario inedito di Girolamo Seriacopi e sui disegni buontalentiani per i costumi del 1589”, in: Il teatro dei Medici. Quaderni di Teatro, II,7 (1980), 157-168.

Arthur R. Blumenthal, Theater Art of the Medici, University press of New England, Hanover (N. H) 1980.

Siro Ferrone, Attori, mercanti, corsari. La Commedia dell’Arte in Europa tra Cinque e Seicento, Einaudi, Torino 1993, nuova ed. Einaudi, Torino 2011.

Siro Ferrone, La Commedia dell’Arte. Attrici e attori italiani in Europa (XVI-XVIII sec.), Einaudi, Torino 2014, nuova ed. Einaudi, Torino 2021.

Elvira Garbero Zorzi, “La tradizione manierista della “meraviglia” nello spettacolo fiorentino del 1589”, in: 44 Settimana musicale senese” Fondazione Accademia Chigiana, 1987, 80-92.

Elvira Garbero Zorzi, “L’Armonia delle arti negli Intermedi buontalentiani del 1589”, in: Magnificenza alla corte dei Medici, Electa, Milano 1997, 265-268; 378-379.

Il luogo teatrale a Firenze, a cura di Mario Fabbri, Elvira Garbero Zorzi, Anna Maria Petrioli Tofani. Introduzione di Ludovico Zorzi, Electa, Milano 1975.

Sara Mamone, Il teatro nella Firenze medicea, Mursia, Milano 1981, nuova ed. Cue Press, Imola (Bologna) 2018.

Sara Mamone, Firenze e Parigi, due capitali dello spettacolo per una regina: Maria de’ Medici, Silvana editoriale, Cinisello Balsamo (Milano) 1988, trad. francese Seuil, Parigi 1990.

Sara Mamone, “La danza di scena negli intermedi fiorentini (1589-1637)”, in: The Influence of Italian Entertainments on Sixteenth and Seventeenth century Music Theatre in France, Savoy and England, a cura di Marie-Claude Canova-Green e Francesca Chiarelli, Edwin Mellen Press, Lewiston (N.Y), 2000, 13-27.

Sara Mamone, “Les Nuées de l’Olympe à la scène: les dieux au service de l’église et du prince dans le spectacle florentin de la Renaissance”, Medioevo e Rinascimento, XXI / n.s. XVIII (2007), 259-274.

Sara Mamone, Il lascito europeo in Dei, semidei, uomini, Bulzoni, Roma 2003, 169-191

Sara Mamone, La macchina e l’indifferenza del mito in Dei, semidei, uomini, Bulzoni, Roma 2003, 193-211.

Sara Mamone, “The Uffizi Theatre. The Florentine Scene from Bernardo Buontalenti to Giulio and Alfonso Parigi”. in: Technologies of Theatre Joseph Furttenbach and the Transfer of Mechanical Knowledge in Early Modern Theatre Cultures, Edited by Jan Lazardzig and Hole RößlerKlostermann, Frankfurt am Main 2016, 389-416.

Alois M. Nagler, Theatre Festival of the Medici, 1539-1637, Yale University Press, New Haven and London 1964.

Frank Mohler, “Medici Wings: The Scenic Wing Change in Renaissance Florence”, in: TD&T: Theatre Design & Technology, 44, 4 (2008), 1-58.

Per un regale evento. Spettacoli nuziali e opera in musica alla corte dei Medici, cura di M. A. Bartoli Bacherini- S. Castelli, Centro Di, Firenze 2000.

Teresa Pasqui, Libro di conti della commedia: la sartoria teatrale di Ferdinando I de’ Medici nel 1589, Nicomp, Firenze, 2010

James M. Saslow. The Medici Wedding of 1589: Florentine Festival as Teatrum Mundi, Yale University Press, New Haven 1996.

Teatro e spettacolo nella Firenze dei Medici, a cura di Elvira Garbero Zorzi e Mario Sperenzi, Olschki, Firenze 2001.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “L’officina delle nuvole. Il Teatro Mediceo del 1589 e gli Intermedi del Buontalenti nel Memoriale di Girolamo Seriacopi”, in: Musica e Teatro. Quaderni degli amici della Scala, VII ,11-12 (1991).

Anna Maria Testaverde, “Michelangelo Buonarroti il Giovane e le didascalie sceniche per il Giudizio di Paride”, in: Studi Di Storia Dello Spettacolo. Omaggio A Siro Ferrone, a cura di S.Mazzoni, Le Lettere, Firenze, 2011, 166-179.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “L’avventura del teatro granducale degli Uffizi (1586-1636)”, in: Drammaturgia, 12 (2016), 45-69.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “Una comedia pastorale in musica [...] su alle stanze del sig.re Don Antonio a Pitti”: l’Euridice per Maria de’ Medici”, in: Dolci trionfi e finissime piegature. Sculture in zucchero e tovaglioli per le nozze fiorentine di Maria de’ Medici, a cura di R. Spinelli, G. Giusti, Sillabe, Livorno 2015, 58-63.

Anna Maria Testaverde, Noveaux documents sur les propotitions scénographique, pp.1-18. Paris, Université Paris 8-Vincennes-Saint Denis, Paris 2018, in: www.musique.univ-paris8.fr, 1-18.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “Elena Povoledo e Niccolò Sabbatini. Fonti per lo studio di un trattato”, in: Illusione e pratica teatrale. Atti del Convegno Internazionale di studi in onore di Elena Povoledo, Le Lettere, Firenze 2016, 83-98.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “La tecnologia scenica e i suoi protagonisti”, in: Vivre sa vie. Centosei lettere di affetto, vita vissuta, teatro e cultura per Luigi Allegri, a cura di M. Bambozzi, A. Bentoglio, Diabasis, Parma 2018, 367-370.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “Exōticós, étranger. La représentation de l’ “l’autre” dans la spectacularité florentine du XVIIe siècle”, in: (a cura di F. Franchi) L’entre-deux de la mode, Éditions L’Harmattan – Bergamo University Press –Sestante Edizioni, Bergamo, 2004, 57-78.

Anna Maria Testaverde, “Creatività e tradizione in una ‘sartoria teatrale’: l’abito scenico per le feste fiorentine del 1589”, in: Il Costume nell’Età del Rinascimento, Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Firenze, Edifir, 1988, 175-187.

D. P. Walker, Les Fetes du mariage de Ferdinand de Médicis et de Christine de Lorraine, Florence 1589. Musique des Intermèdes de La Pellegrina, Éditions du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris 1963.

Aby Warburg, “I costumi teatrali per gli Intermezzi del 1589: i disegni di Bernardo Buontalenti e il ‘Libro di conti’ di Emilio de’ Cavalieri”, in: Atti dell’Accademia del R. Istituto Musicale di Firenze: Commemorazione della Riforma Melodrammatica, XXXIII (1895), 133-146 poi edito in: Aby Warburg, Gesammelte Schriften. Die Erneuerung der Heidnischen Antike: Kulturwissenschaftliche Beiträge zur Geschichte der europäischen Renaissance, Teubner, Leipzig-Berlin 1932, 259-300; 394-438.

Ludovico Zorzi, Il teatro e la città, saggi sulla scena italiana, Einaudi, Torino, 1977.

Credits for images

Firenze, Biblioteca Marucelliana; Firenze, Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale; Firenze, Città metropolitana, Villa di Pratolino; Firenze, Fratelli Alinari I.d.e.a. S.p.A.; Firenze, Galleria degli Uffizi; Firenze, Musei Civici fiorentini, fototeca Musei Comunali; Firenze, Ovidio Guaita per Galleria Palatina di Firenze; Genova, Dynamic srl; London, Victoria & Albert Museum; New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art; Paris, Musée du Louvre, Cabinet des Dessins; Siena, Archivio di Stato; Torino, C&C di Enrico Carlesi; Vienna, Theatermuseum.

Acknowledgements

Ricciardo Artusi; Marusca Bacciotti; Luca Bellingeri; Cinzia Cardinali; Enrico Carlesi; Silvia Castelli; Alberto Dellepiane; Roberto Gabucci; Giovanni Martellucci; Stefano Mazzoni; Laura Monticini; Giovanna Pecorilla; Susanna Pelle; Muriel Prandato.

Credits

Title: Gli Intermedi de La Pellegrina (1589)

Authors: Siro Ferrone (Università di Firenze), Sara Mamone (Università di Firenze), Anna Maria Testaverde (Università di Bergamo)

Storyboard editing: Rudi Risatti

Voice: Alexander McCargar

English Translation / Proof Reading: Elena Mazzoleni / Erin Coghill

Web Design: Kunsthistorisches Museum – Visual Media, Vienna