Scenography and Venetian Painting

Carmen González-Román

Space and Figures

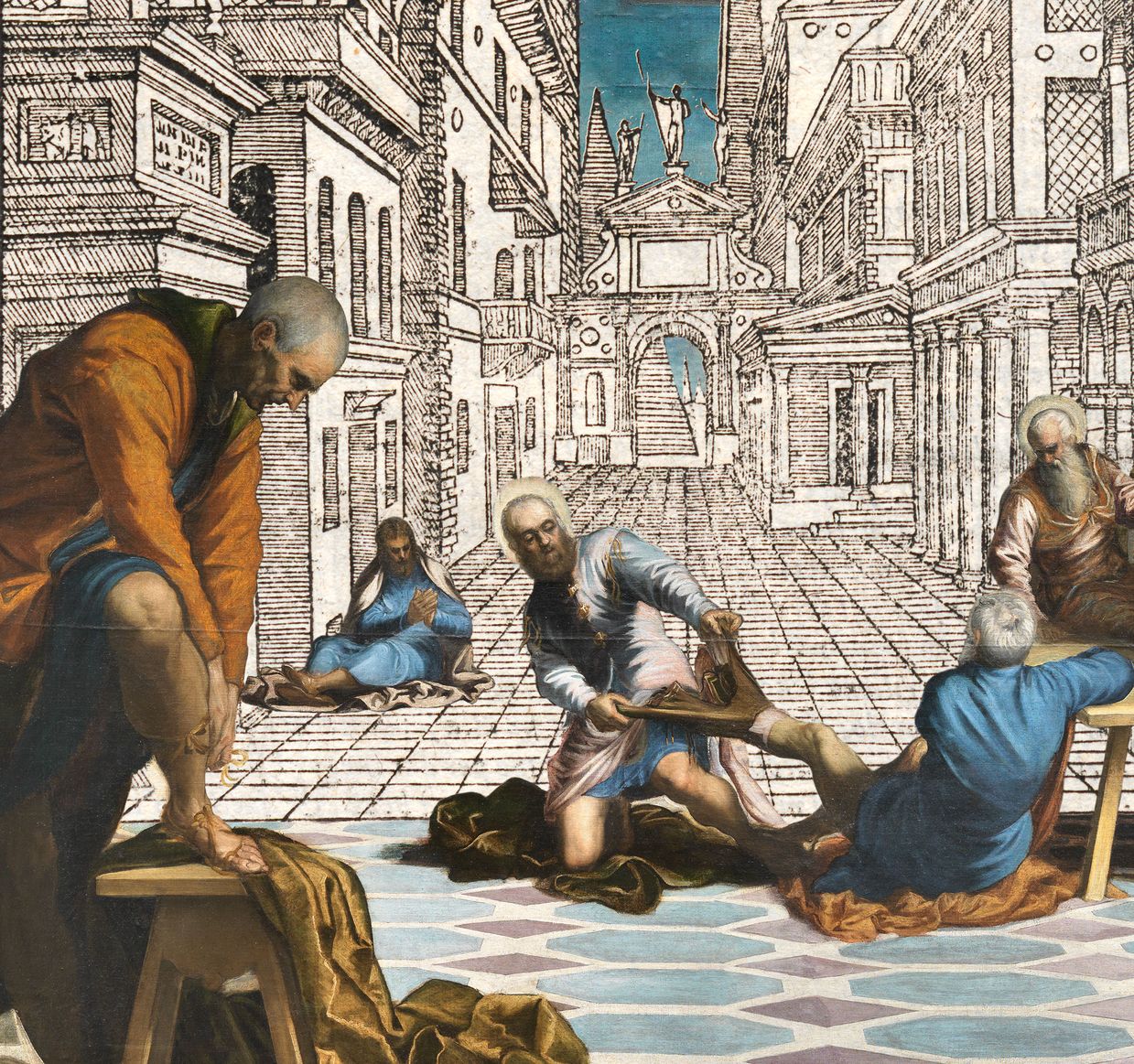

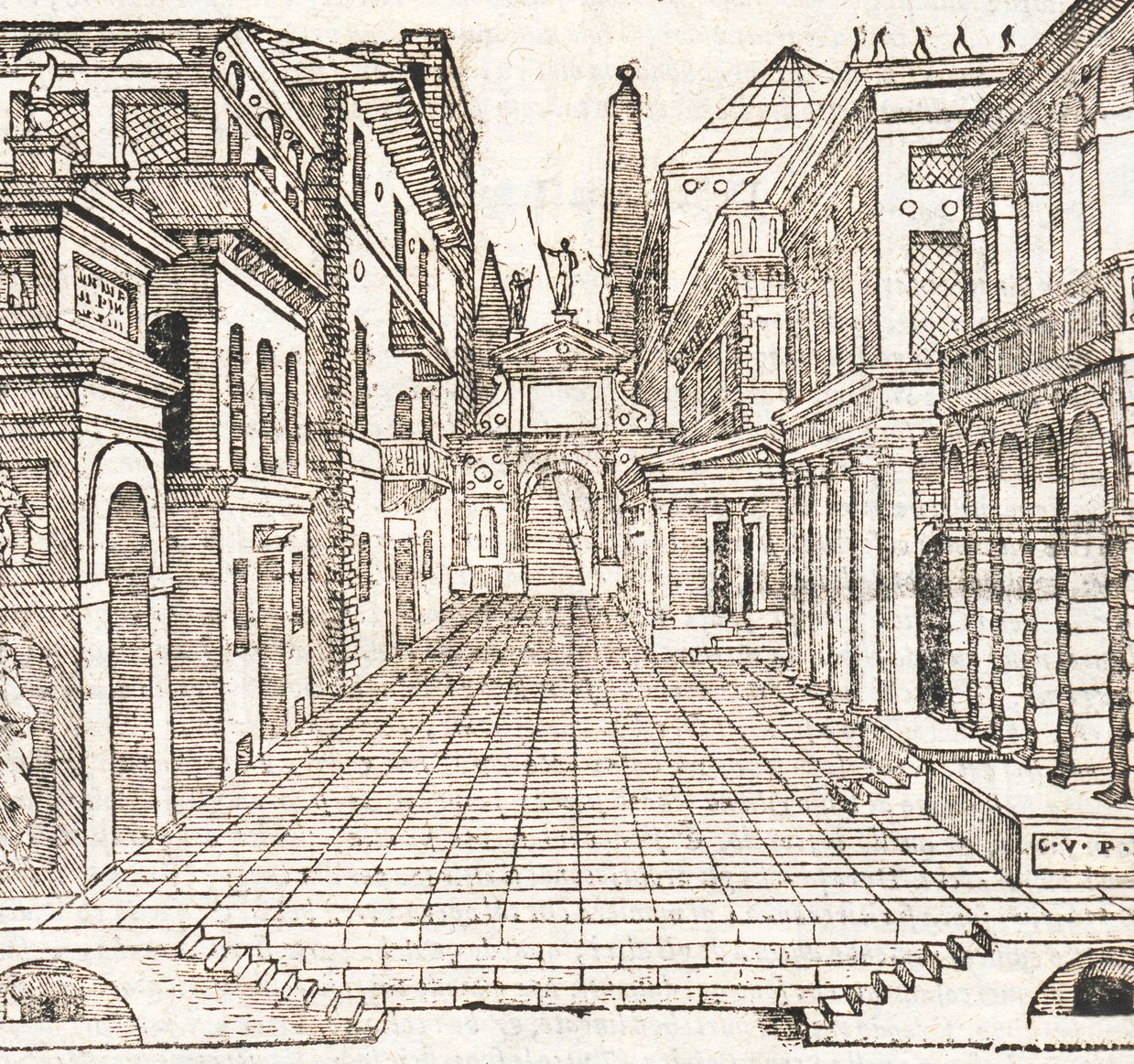

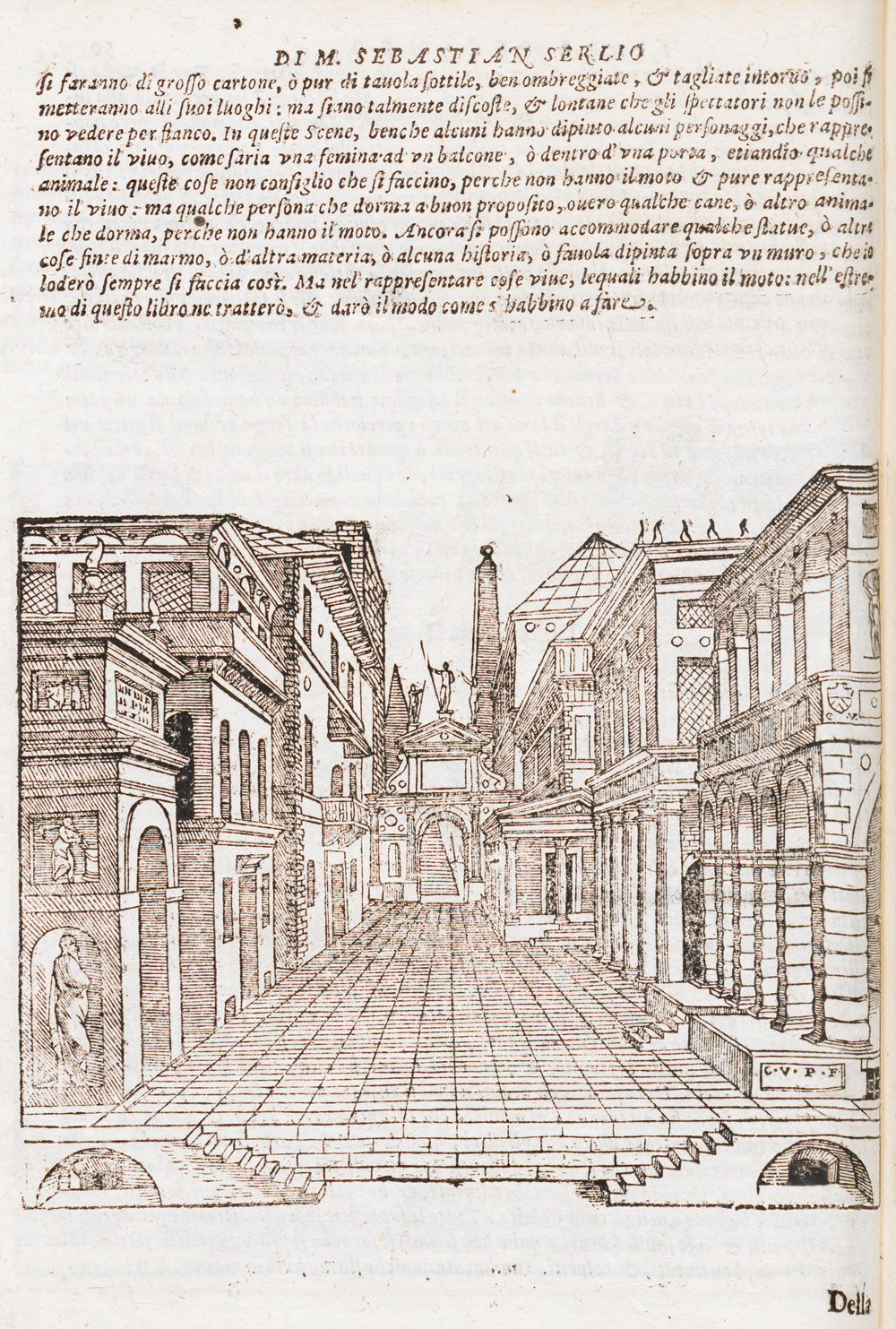

In Jacopo Tintoretto’s The Washing of the Feet we find a cityscape inspired by the stage designs of the Italian architect Sebastiano Serlio who included a book on perspective in his treatise on architecture – Il Secondo Libro di Prospettiva, di Sebastiano Serlio, Bolognese, Paris 1545.

Serlio's treatise was the first to include a chapter dedicated to the stage and scenography. It was followed by a number of treatises on perspective that developed various theories and methodologies for the design of scenery.

Literature on scenography and perspective at the time

In 1545, the Bolognese architect Sebastiano Serlio published Il Secondo Libro di Perspettiva, which contained the first Trattato sopra le scene. It included stage designs for tragedy, comedy and satire, as described by the Roman architect Vitruvius in the first century BC. After Serlio, most treatises on perspective devoted a chapter to stage design.

After Serlio’s theoretical development, Daniele Barbaro published La pratica della perspettiva (Venice, 1569), in which part four deals with the descriptione delle scene. In the description of the scena tragica, Barbaro explains his concept of ‘scenario’ and the method he recommended for drawing the perspective.

In 1583, Regole della prospettiva prattica, a treatise by Jacopo Barozzi da Vignola was published in Rome, with notes by Ignazio Danti. The First Rule of Vignola’s treatise contains a section entitled: Del modo che si tiene nel disegnare le Prospettive della Scene…

The treatises on perspective by Lorenzo Sirigatti and Guidobaldo del Monte represent the culmination of sixteenth-century studies on scenography, and were followed by treatises reflecting new approaches to perspective and stagecraft in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

Tintoretto invented costumes and stage sets that amazed the spectators

It was no coincidence that Tintoretto, one of the great masters of the Venetian school, used Serlio’s designs for tragic scenes in the backgrounds of his paintings since, throughout his career, he also dedicated much of his time to the design of costumes and sets for various productions of comedies in Venice.

According to his biographer Carlo Ridolfi he:

“invented original and ingenious costumes, and many of them for the representation of the comedies that were recited in Venice ... He invented many curiosities that amazed the spectators, and were celebrated as extraordinary, so that everyone came to him for similar occasions”

Translated from Carlo Ridolfi, Vita de Giacopo Robusti detto il Tintoretto […] Venice, 1642, 88.

Tintoretto had close links with a group of poets, publishers and theatre specialists in Venice, known as the Polygraphs, and one of his closest friends was the Venetian actor and writer of comedies Andrea Calmo.

Through his biographer we also know that Tintoretto was involved in the decoration of some of the great scenographic sets erected in the city of Venice, such as the ephemeral arch constructed in the Lido for the landing of Henry III, King of France (crowned in 1575).

Carlo Ridolfi explains in another well-known passage from the life of Tintoretto, that he used "curious artifices" as aids in his painting. These consisted of small wax and clay models dressed in rags which enabled him to study the drapery folds and the areas of exposed flesh. He placed these figures inside "little houses and perspectives, made out of wood and paperboards". The vivid description suggests that these artifices should be interpreted as small theatres that proved to be, according to Ridolfi, "extraordinary inventions".

The backdrop painted by Tintoretto in this painting is a unique example of metascenography.

The term metascenography refers here to the use of a backdrop painted in illusionistic perspective located behind the main scene of a painting. That scene is, in turn, usually framed by painted architectural elements (further examples in Venetian painting to be explored later). The metapictorial content found in European painting from the Early Modern Period has attracted the interest of prestigious scholars who have been keen on interpreting the diverse influences and artifices used by the painters of these works. Julián Gállego stated as such in his influential book Visión y símbolos en la pintura española del Siglo de Oro (1972). Two decades later, Victor Stoichita published L'instauration du tableau. Métapeinture à l'aube des temps modernes (1993),

where he expanded exponentially on the ideas of Gállego and through a detailed study of hermeneutics clarified the function and meaning of the metapictorial motifs found in the works. More recently, the exhibition curated by Javier Portús at the Museo Nacional del Prado and the accompanying catalogue Metapintura. Un viaje a la idea del arte en España (2016), again travelled through the world of images in painting, this time within the context of the Spanish Golden Age. Despite all this research, however, the reverberations felt from the use of a painted background inspired by illusionistic scenery and located behind the architectural elements that frame the main scene of a painting have rarely been analysed. Find out more

The Urban Space

Very early graphic and literary testimonies from Italy have been preserved which demonstrate the use of urban views in perspective studies

The earliest representation of this type of scenery can be inferred from a dramatic text by Leon Battista Alberti, the comedy Filodoxo, written in Bologna shortly after 1425, but reworked later and dedicated to Lionello d'Este in 1436 or 1437.

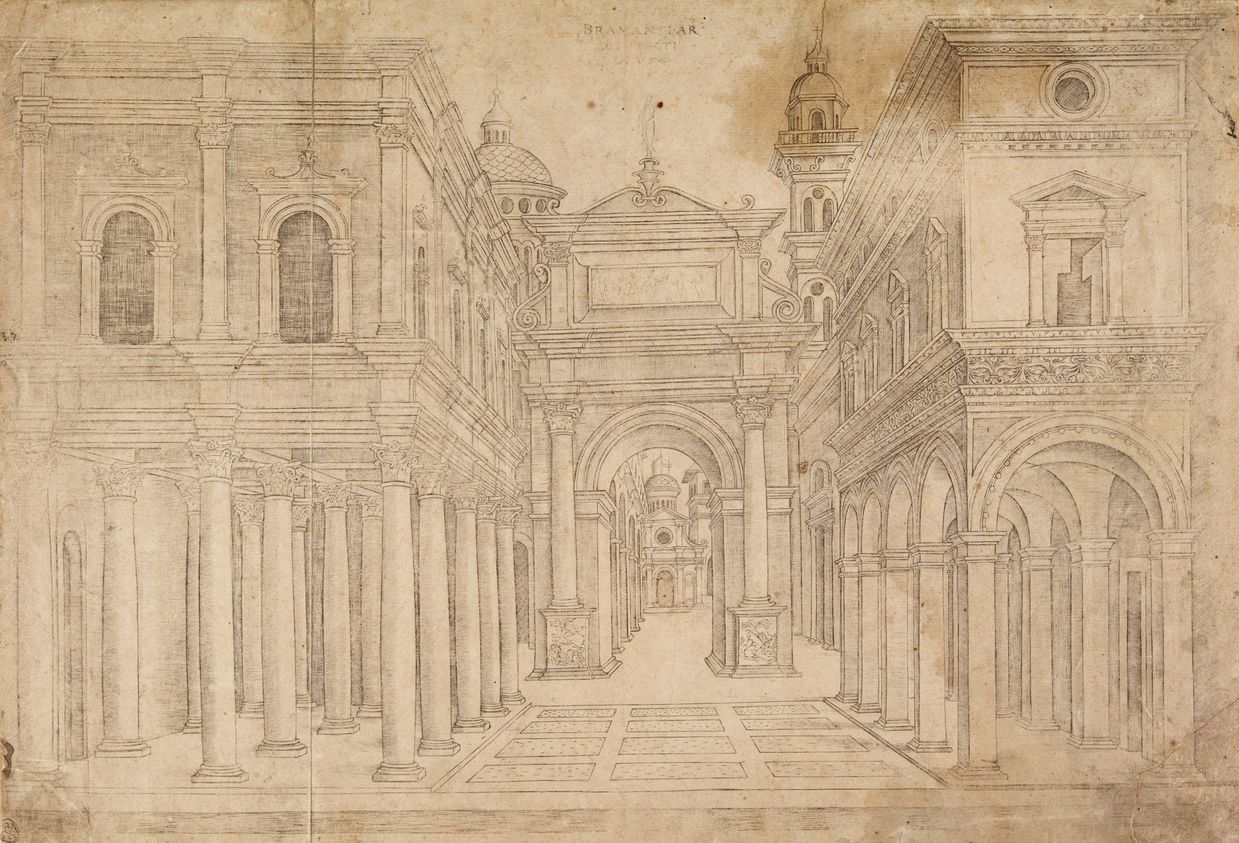

In 1508 Ariosto’s Cassaria was performed in Ferrara, which utilized a backdrop that reproduced a view of a landscape with multiple urban elements. Five years later, in the performance of Cardinal Bibbiena's Calandria, in Urbino (1513), a perspectival backdrop in combination with trompe-l'oeil low reliefs on the sides was used for the first time on stage. The author of this set was Girolamo Genga, an artist originally from Urbino who had just finished working in Rome with his compatriot Donato Bramante.

The staging of I Suppositi by Ariosto was another milestone in the use of urban views in scenography. The staging in Rome, in the hall of Cardinal Innocenzo Cybo during the carnival of 1519, was identified by Christoph Luitpold Frommel in a drawing by Raphael preserved in the Uffizi.

“La scena poi era finta una città bellissima con le strade, palazzi, chiese, torri, strade vere e ogni cosa di rilievo, ma aiutata ancora da bonissima pittura, e prospettiva bene intesa”

“In the scene a beautiful city was suggested, with streets, palaces, churches, towers, real streets and each thing made in relief but also assisted by a very good painting and a well understood perspective”.

Baldassare Castiglione. “Al conte Lodovico di Canossa Vescovo di Tricarico”. Lettere del conte Baldessar Castiglione, Padova, 1769, p. 157. (Description of the comedy Calandria performed in Urbino, 1513).

The Ideal City

The ideal cities represented in the so-called »Urbino Perspectives« (similar ones can be found in Baltimore and Berlin), were initially interpreted as projects for scenography because they share a similar composition with scenographic studies.

The scena di città is a stylistic trend that originated during the Italian Renaissance and is found both in the visual arts and in the theatre. It is related, in its way of representing space, to perspective.

The shallow perspective, used to create the scena di città, appears in works of the early Renaissance in which there are galleries of arches behind the main scene to accentuate the depth.

In the painting of the Quattrocento we find a balanced spatial organization in which the lines formed by paving stones on the ground determine the perspective. The vanishing point coincides, generally, with the place occupied by a centralized building. This is the compositional scheme followed by Perugino in Christ Giving the Keys to St. Peter (ca. 1481).

Scenography depicting stately urban landscapes, with palaces, temples and ancient monuments, represents an ideal model in keeping with the image of the city in classical antiquity, and is found both in painting and on stage.

The Tragic Scene and Bordone

Similar scenographic backgrounds can be found in paintings by artists related to the Venetian school.

“In this painting the relationship between painting and theatre is inverted, that is, the theatrical perspective also transforms the work into a painted theatre.”

Hans Belting, Florence and Baghdad, 2012

The urban scene inspired by the tragic scene of Serlio is represented in this painting by Bordone.

“Nell´Architettura poi fece marauiglie: poiche si vedono esempij di sfuggimenti di Prospettiua cosi bene rappresentati che formano concerti di rarità”

“In Architecture he then did wonderful things: we see examples of perspective so well represented that they form compositions of rarities”

Marco Boschini, Le ricche minere della pittura veneziana. Venice, 1674

The Tragic Scene and El Greco

Other paintings by El Greco from his Italian period repeat similar compositions in which monumental classical architecture is arranged following Serlio’s scenographic perspective studies.

The Tragic Scene and Veronese

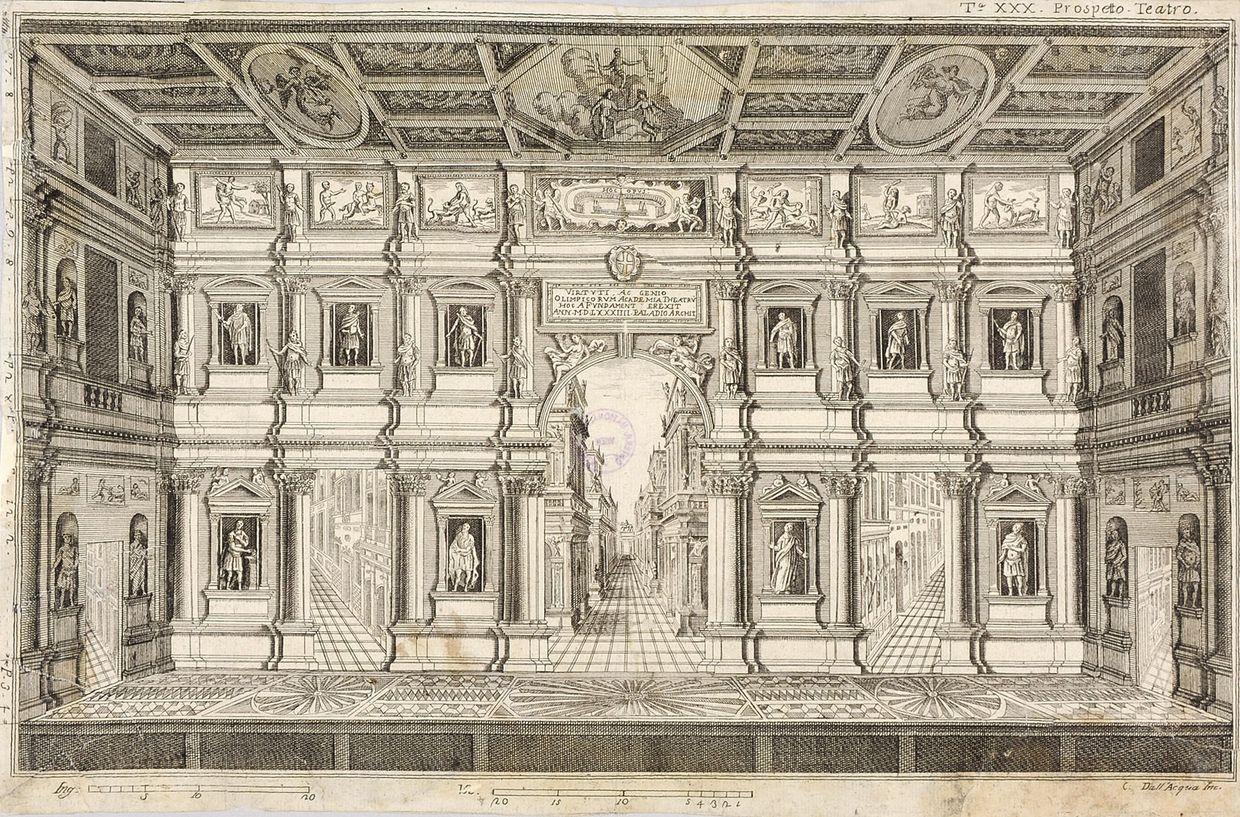

The contact of Venetian painters with the architect Andrea Palladio was decisive for the scenographic conception of some of the best known paintings of this school.

Paolo Veronese, together with Tintoretto, intervened in the decoration of large urban installations built in the city of Venice, such as the ephemeral arch raised on the Lido for the landing of Henry III, King of France (crowned in 1575). Both artists worked under the direction of the famous architect Andrea Palladio, who had already designed a wooden theatre in the classical manner in Vicenza. Around 1564/65,

Palladio built another temporary theatre, possibly in the cloister of the monastery of La Carità, whose stage would have a frons scaenae with a triple passage behind and views of street scenes in perspective. Of the wooden theatres built by Palladio, only descriptions have survived, however all of Palladio’s experimentation would come to use years later in the design of the extraordinary Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza.

In Christ at a Meal in the House of Levi (1573), Veronese places the characters in an extraordinary portico conceived in the manner of a frons scaenae while behind he painted a backdrop depicting a city.

This backdrop is a unique example of metascenography, that is, a perspectival view located behind the more shallow architecture that frames the main scene of the painting.

Sources

Carlo Ridolfi, Vita de Giacopo Robusti detto il Tintoretto […], Venecia 1642

Marco Boschini, Le ricche minere della pittura veneziana, Venecia 1674

Selected Bibliography

Antonio Bonet Correa, “La perspectiva, el territorio y la escenografía renacentista en Maquiavelo”, Boletín de Arte, 25 (2014), 27–41. Available at: http://www.revistas.uma.es/index.php/boletin-de-arte/article/view/3367.

Carmen González-Román, Spectacula. Teoría, arte y escenaen la Europa del Renacimiento. Universidad de Málaga – Real Academia de BB.AA. de San Telmo, Málaga 2001.

Carmen González-Román, "Metaescenografías pintadas", Espacio, Tiempo y Forma, Serie VII, 7 (2019), 77-101.Available at: http://revistas.uned.es/index.php/ETFVII/article/view/24267.

Hans Belting, Florencia y Bagdad. Una historia de la mirada entre Oriente y Occidente. Akal, Madrid 2012.

Miguel Falomir, “El Greco y la pintura veneciana”, Archivo secreto. Revista cultural de Toledo, 6 (2015), 253–262.

Miguel Falomir, Una obra maestra restaurada. El Lavatorio de Jacopo Tintoretto. Museo del Prado, Madrid 2000.

Miguel Falomir, Tintoretto. Museo del Prado, Madrid 2007.

Cecil Gould, “Sebastiano Serlio and Venetian Painting”, Journal of the Warburg and CourtauldInstitutes, 25 (1962), 56-64.

Marsel Grosso, Tintoretto e l´architettura. Marsilio, Venezia 2018.

Vicente Molina Foix, Tintoretto y los escritores. Galaxia Gutenberg, Madrid 2007.

Yves Pauwels, “La cultura arquitectónica y los decorados de la pintura en los siglos XVI-XVII”, en: Arquitecturas pintadas. Del Renacimiento al siglo XVIII. Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid 2011, 73–86.

David Rosand, “Theater and Structure in the Art of Paolo Veronese”, en: David Rosand, Painting in Cinquecento Venice. Titian, Veronese, Tintoretto. Yale University Press, New Haven 1982.

Digital Resources

Carmen González-Román: “Escenografías all'italiana en el Museo del Prado: de Tintoretto al Greco”. Conference delivered at Museo del Prado (25-5-2017): https://www.museodelprado.es/actualidad/multimedia/escenografias-allitaliana-en-el-museo-del-prado/0db02be5-531d-4873-9e7c-2af146e0e291

Carmen González-Román: “Escenografías all'italiana en la España de Felipe II”, Goya nº 331, 2010: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/294392793_Italian-style_Scenographies_in_the_Court_of_Philip_II

Miguel Falomir: “The Washing of the Feet” by Tintoretto. Commented by the Director of the Museo Nacional del Prado on the occasion of the Bicentenary celebration: https://www.museodelprado.es/actualidad/multimedia/el-lavatorio-de-tintoretto/e42f492b-ecdf-2b08-9277-5eac5e4da24f