The Heaven Machinery

in the Florentine Theatrical Tradition

Alessandra Buccheri

The Heaven Machinery

... was a sophisticated theatrical device representing the Heavens, used in Florence during some of the performances associated with religious drama.

Mostly built inside churches, such machines were made of wood and had a large round aperture that opened upwards revealing a dome containing the nine circles of Heaven.

Attached to the lower end of a movable Mandorla, was a small platform, covered with wadding, on which a holy character could stand as if he or she was on a cloud.

Sometimes, other little platform-clouds would be added to the sides, supporting more angels.

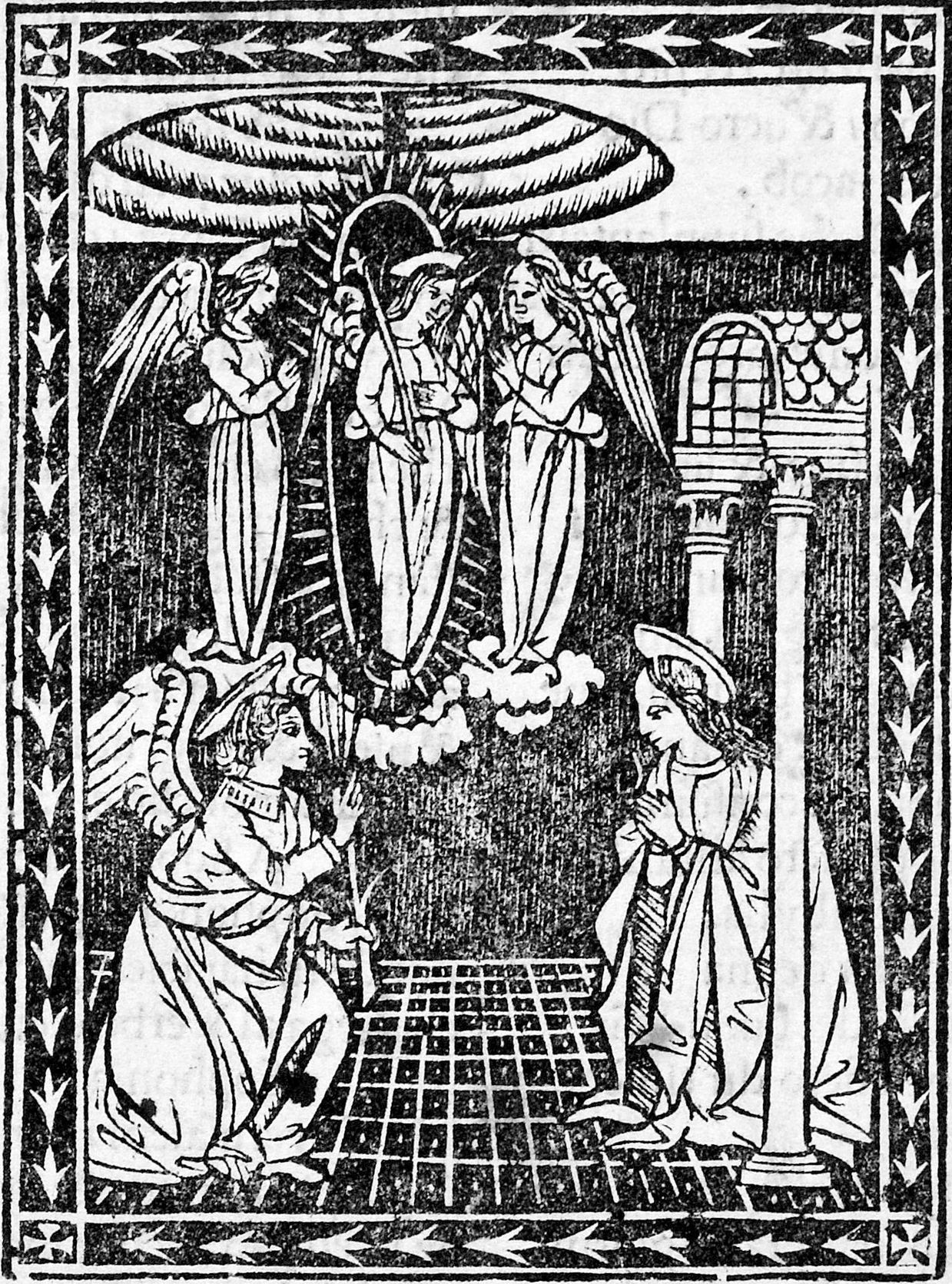

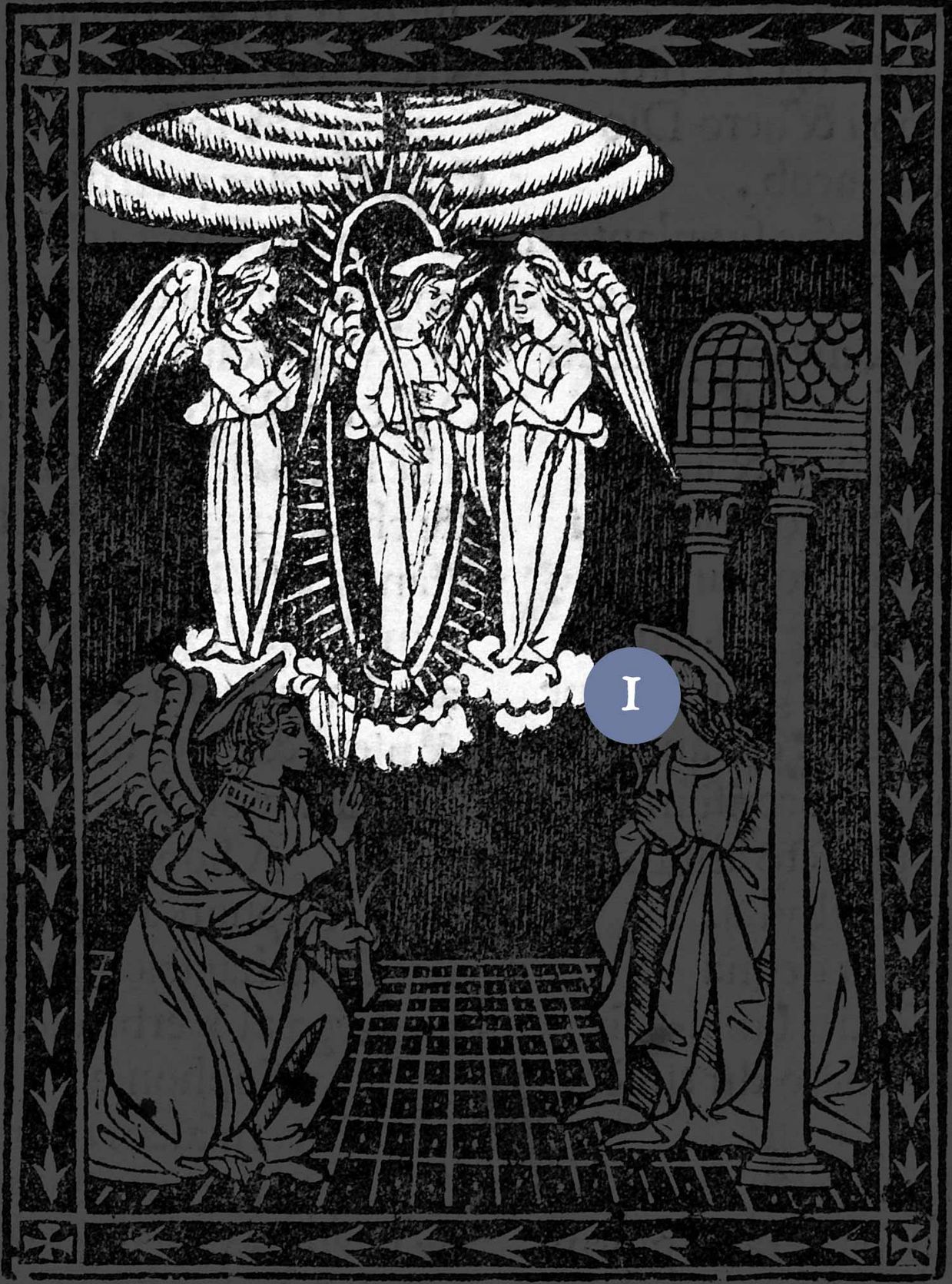

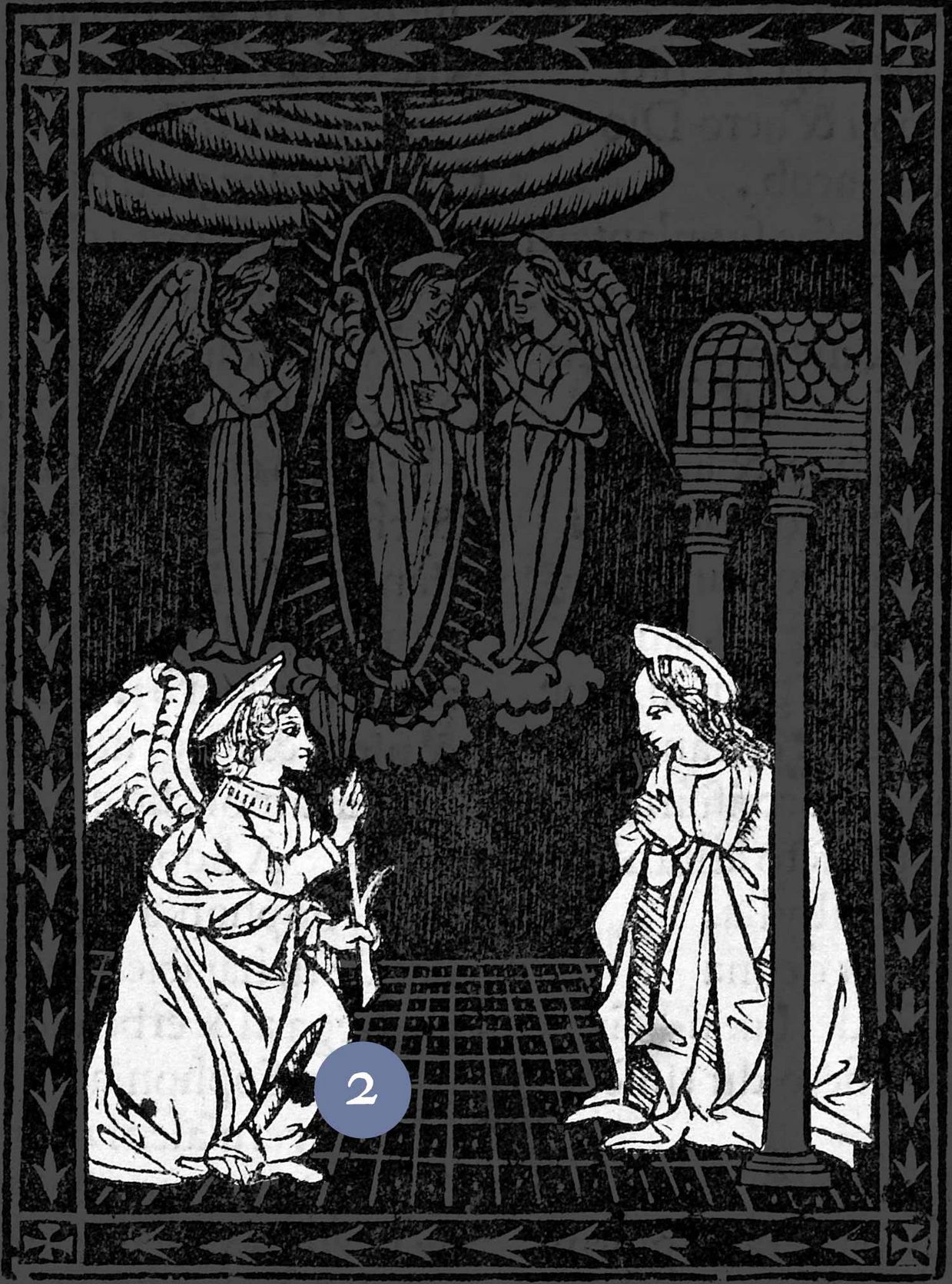

This woodcut, dating to c. 1500, is the first graphic record of the Heaven Machinery

Here, the Heaven Machinery is used to perform the episode of the Annunciation, which was usually staged inside the Florentine church of San Felice in Piazza during the Annunciation Feast on the 25th of March, or on the occasion of other important events, such as marriages of members of the Medici, the ruling dynasty in Florence at that time, or visits of foreign rulers, etc.

The Mandorla

In Christian iconography, the mandorla is the divine light that surrounds holy characters, including angels, when they appear on earth. In the tradition of religious drama, the mandorla became a type of theatrical machine used to carry the holy characters up and down from an artificially built Heaven.

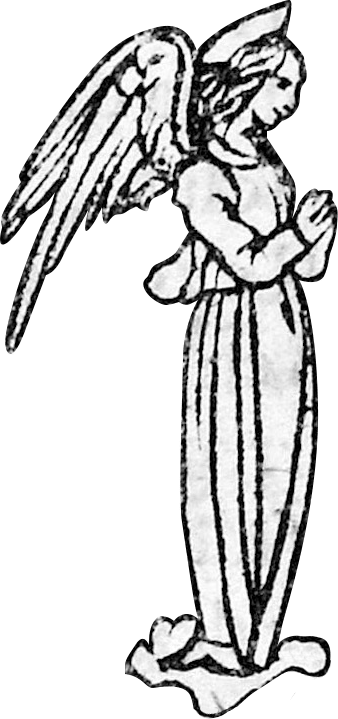

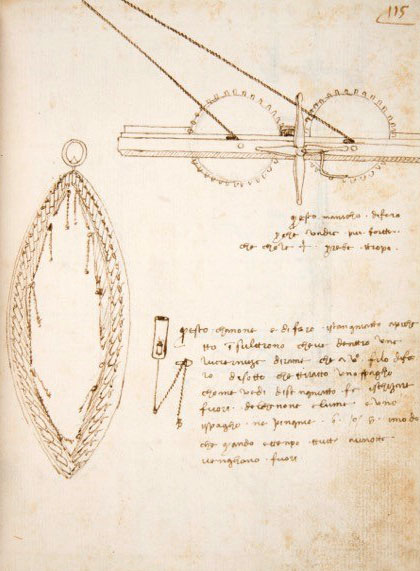

This rare drawing by Buonaccorso Ghiberti, grandson of the more famous Lorenzo, describes the technical system of this machinery. The iron framed mandorla was used as a lift. The holy character would be standing inside of it, as one can see in the mandorla carrying Gabriel, which is represented in the woodcut of the Annunciation.

The mandorla was moved up and down by means of a system of pulleys and ropes - represented at the top of the drawing - and it was often equipped with a lighting system. The lights, located all around the mandorla, were candles placed inside little iron cylinders, as shown in the drawing accompanied by a description. The cylinders, which could move up and down, showed the light of the candles only when lifted up, allowing special light effects.

The mandorla was often placed on a cloud, a platform covered with wadding, as shown in the woodcut of the Annunciation. Sometimes the mandorla itself was covered with wadding, resembling a cloud.

The Annunciation Feast

The Annunciation was a common theme of religious drama across Europe. In Florence, the Annunciation was one of the most important feasts, given the special devotion of the city to the Virgin Mary.

In the second half of the Cinquecento, the Annunciation play, traditionally staged inside the church of San Felice in Piazza, was moved to the church of Santo Spirito by Giorgio Vasari.

This woodcut represents two moments of the story in chronological sequence:

1 In the background Gabriel is descending from Heaven on a cloud

2 In the foreground, he is announcing his message to the Virgin Mary

While the Heaven Machinery was anchored to the beams of the ceiling, the portico where the Virgin Mary was, surprised by Gabriel’s arrival, was located on scaffolding built for the occasion. Since women were not allowed to act, both the parts of the angels and the Virgin Mary were acted by young boys.

The Annunciation Feast has been documented in Florence since the mid of the 15th century. However, such traditional feasts most probably started long before their first appearance in the records. It is possible that the Annunciation play had already been performed in Florence at the start of the 15th century, or even earlier.

In 1553, the Annunciation Feast had a sudden interruption when the church of San Felice passed from the Camaldolese monks to the Dominican nuns of St. Peter Martyr, who did not allow staging the play inside their church. The Annunciation machinery was then removed from San Felice and stored in a room off the Cloister of the Carmine, where Giorgio Vasari found it later on, together with other stage machinery, which he restored and used for the 1566 Annunciation play in Santo Spirito.

Theatre and Painting

The same structure described in the woodcut of the Annunciation is present in the Assumption of the Virgin, painted by the Florentine Francesco Botticini around 1475.

The heavenly dome, imbedded in a rigid, wood-like blue sky, includes the nine angelic hierarchies. Botticini’s panel is the first known example in which Heaven is represented in such a manner.

For this reason, it has been considered as quite a straightforward example of the influence of religious drama on figurative art.

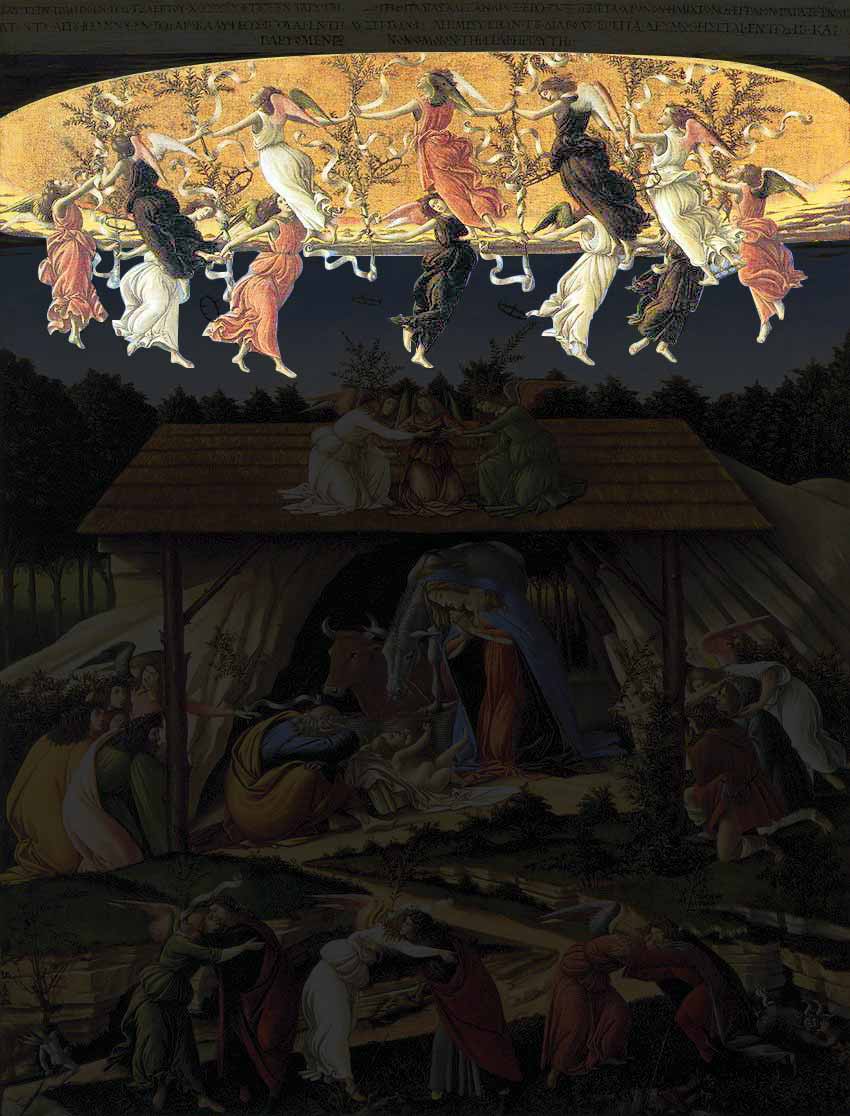

The same majestic opening revealing Heaven represented in the woodcut of the Annunciation and in Botticini’s Assumption, is present in the Mystical Nativity, painted by Sandro Botticelli (1445–1510) around 1500.

Botticelli’s painting also shows another typical feature of performances associated with Heaven Machinery: the dancing angels standing at the edges of Heaven, holding each other’s hands. The dancing angels are also present in Giorgio Vasari’s Heaven Machinery, designed in 1566.

Giorgio Vasari’s Heaven Machinery

The famous artist and historian Giorgio Vasari designed the Heaven Machinery for the Annunciation Feast, staged on the occasion of the marriage of Francesco de’ Medici to Johanna of Austria, celebrated in 1566 in the church of Santo Spirito in Florence.

There are no depictions of that play; therefore, there is little information about the details of the performance. However, on the basis of various historical records, we propose an image, which gives a general idea of how the original machinery worked. This reconstruction is based on two main descriptions written by Domenico Mellini, a man of letters of the Medici court, and Giorgio Vasari:

“The stage for the representation was constructed under the Cupola […] and Paradise appeared open and full of stupendous splendour, and in it God the Father amidst a multitude of Angels and Cherubim, and told the Angel Gabriel to descend to earth and announce to the Virgin Mary the Incarnation of his Son. Then the Angel Gabriel in a beautiful mandorla all full of lights descended slowly to earth, and above him then was a Choir of Angels that descended with him half way then stopped, and the mandorla where the Angel Gabriel was then went down slowly by itself to earth, and when it arrived there he stepped out of the mandorla and immediately all the lights and splendour of the mandorla were displayed, and moving slowly with most beautiful grace he went before the Virgin, and with a voice that was almost divine, he told her of God’s message”

Differing from Mellini, Giorgio Vasari’s description is not explicitly related to his Heaven Machinery of 1566, but to Filippo Brunelleschi’s apparatus used for the Annunciation Feast in Florence, probably in the 1430s. The description is from The Lives, where Vasari writes about the tradition of Heaven Machinery (Ingegni del Paradiso) in Florence and describes it in detail.

We know, however, that Vasari might have been unaware of the technology used at the time of Brunelleschi, since he learned everything about such apparatuses only by looking at the machines that were still existent in the early 1560s. After he found the heaven machines stored in the Cloister of the Carmine, he restored them and used them in the Church of Santo Spirito to perform a revived version of the Annunciation feast.

In fact, as Vasari describes Brunelleschi’s apparatus for the Annunciation Feast, he clearly describes his own, creating an implicit link with the famous Florentine architect. The following description comes from the biography of Brunelleschi included in The Lives:

“Filippo had suspended, between two of the beams that supported the roof of the church, the half of a globe in the shape of an empty bowl, or rather, a barber basin, with the rim downwards […].

At the foot of the inner edge it had certain wooden brackets, large enough for one person to stand on […]; on each of these brackets there was placed a boy […]. These boys, who were twelve in all, were […] dressed like angels, […] and when it was time they took one other by hand and waved their arms, so that they appeared to be dancing, and the half globe was ever moving and turning around. Within it, above the heads of the angels, were three circles or garlands of lights, contained in certain little lamps that could not be overturned. From the ground these lights appeared like stars, and the brackets, being covered with cotton wool, appeared like clouds.

From the aforesaid ring there issued a very stout bar of iron […]. The said stout bar of iron had eight arms, spreading out in an arc large enough to fill the space within the hollow half globe, and at the end of each arm there was a stand about the size of a trencher; on each stand was a boy about nine years old, well secured by an iron soldered on to the upper part of the arm, but loosely enough to allow him to turn in every direction.

These eight angels, supported by the said iron, were lowered from the space within the half-globe […] in such a manner that they were seen without concealing the view of the angels who were round the inner edge of the half-globe. In the midst of this cluster of eight angels –for so was it rightly called– was a mandorla of copper, hollow within, wherein were many holes showing certain little lamps fixed on iron bars in the form of tubes; which lamps, on the touching of a spring which could be pressed down, were all hidden within the mandorla of copper, whereas, when the spring was not pressed down, all the lamps could be seen alight through some holes therein.

When the cluster of angels had reached its place, this mandorla, which was fastened to the aforesaid little rope, was lowered very gradually […], and arrived at the platform where the representation took place; […]. He then returned into the mandorla, […] and was drawn up again; while the singing of the angels in the cluster, and of those in the Heaven, who kept circling around, made it appear truly a Paradise, and the rather because, in addition to the said choir of angels and to the cluster, there was a God the Father on the outer edge of the globe, surrounded by angels similar to those named above and supported by irons, in such wise that the Heaven, the God the Father, the cluster, and the mandorla, with innumerable lights and very sweet music, truly represented Paradise”.

Sources

Ricordi intorno ai costumi, azioni, e governo del sereniss. gran duca Cosimo I. scritti da Domenico Mellini di commissione della serenissima Maria Cristina di Lorena ora per la prima volta pubblicati con illustrazioni, Firenze 1820.

Giorgio Vasari, Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors & Architects, edited by Gaston Duc De Vere, 10 volumes. London, 1912-5.

Giorgio Vasari, Le vite de’ più eccellenti pittori scultori e architettori: nelle redazioni del 1550 e 1568, editors: Paola Berocchi and Rosanna Bettarini - 6 volumes. Florence 1966.

Selected Bibliography

Giovanna G. Bertelà, Annamaria Petrioli Tofani, Feste e apparati medicei da Cosimo I a Cosimo II, Florence 1969.

Giorgio Bonsanti, Silvia Castelli, Anna Maria Testaverde, Sacred Drama. Performing the Bible in Renaissance Florence / La Sacra Rappresentazione. Recitare la Bibbia nella Firenze del Rinascimento, Oklahoma City – Museum of the Bible, 2018.

Otto Brendel, “The Origin and Meaning of the Mandorla”, Gazette des Beaux-Arts, XXV, 86, 1944.

Alessandra Buccheri, The Spectacle of Clouds, 1439-1650. Italian Art and Theatre, Farnham 2014.

Alessandro D’Ancona, Origini del teatro in Italia: studj sulle sacre rappresentazioni seguiti da un'appendice sulle rappresentazioni del contado toscano, 1st edition, 2 volumes, Florence 1877.

Mario Fabbri, Elvira Garbero Zorzi, Anna Maria Petrioli Tofani, Ludovico Zorzi, Il Luogo teatrale a Firenze: Brunelleschi, Vasari, Buontalenti, Parigi, Milan 1975.

Elvira Garbero Zorzi, Mario Sperenzi, Teatro e spettacolo nella Firenze dei Medici: modelli dei luoghi teatrali, Florence 2001.

Sara Mamone, Il teatro nella Firenze medicea, Milan 1981.

Sara Mamone, “Les nuées de l’Olympe à la scène. Les Dieux au service de l’Église et du prince dans le spectacle florentin de la Renaissance”, in: Medioevo e rinascimento, Fondazione Centro Italiano di Studi sull’Alto Medioevo, Spoleto 2007, 259-274.

Peter Meredith, John E. Tailby, The staging of religious drama in Europe in the later Middle Ages: texts and documents in English translation, Western Michigan University 1983.

Nerida Newbigin, Feste d'Oltrarno: Plays in Churches in Fifteenth-century Florence, 2 volumes, Florence 1996.

Nerida Newbigin, “Greasing the Wheels Of Heaven: Recycling, Innovation and the Question Of "Brunelleschi’s" Stage Machinery”, in: I Tatti Studies in the Italian Renaissance, Vol. 11 (2007), pp. 201-241.

Roberta J.M. Olson, “Brunelleschi’s Machines of Paradise and Botticelli’s Mystic Nativity”, in: Gazette des Beaux-Arts, 123, 1981, pp. 183-188.

Gotz Poshat, “Brunelleschi and the Ascension of 1422”, in: The Art Bulletin, LX, 2, 1978, pp. 232-4.

Anna Maria Testaverde Matteini; Anna Evangelista, Sacre rappresentazioni manoscritte e a stampa conservate nella biblioteca nazionale centrale di Firenze: inventario, Florence–Milan 1988.

Anna Maria Testaverde Matteini, “Teorie e pratiche nei progetti teatrali di Giorgio Vasari", in: Percorsi Vasariani, editors: Maddalena Spagnolo, Paolo Torriti, Montepulciano 2004, pp. 63-75.

Paola Ventrone, Teatro civile e sacra rappresentazione a Firenze nel Rinascimento, Florence 2016.

Ludovico Zorzi, “La scenotecnica brunelleschiana. Problemi filologici e interpretativi”, in: Filippo Brunelleschi, la sua opera e il suo tempo, Florence 1980, pp. 161-71.

Title: The Heaven Machinery in the Florentine Theatrical Tradition

Author: Alessandra Buccheri (Accademia di belle Arti di Palermo) alessandra.buccheri@abapa.education

English Translation and Proof Reading: Alessandra Buccheri, Alexander McCargar

Web Design: Kunsthistorisches Museum – Visual Media, Vienna

Photographic Sources: Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze (images 1, 2), Chiara Buccheri (image 3), National Gallery London (images 4, 5).